views

Looking for Visual Identifiers

Discern if the rock is black or rusty brown. If the rock you’ve found is a freshly fallen meteorite, it will be black and shiny as a result of having burned through the atmosphere. After a long time spent on Earth, however, the iron metal in the meteorite will turn to rust, leaving the meteorite a rusty brown. This rusting starts out as small red and orange spots on the surface of the meteorite that slowly expand to cover more and more of the rock. You may still be able to see the black crust even if part of it has begun to rust. The meteorite may be black in color but with slight variations (e.g., steely bluish black). However, if the rock you’ve found isn’t at all close to black or brown in color, then it is not a meteorite.

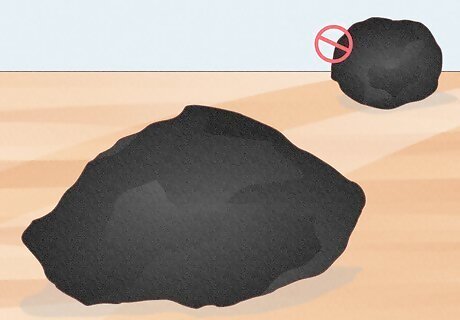

Confirm that the rock has an irregular shape. Contrary to what you might expect, most meteorites are not round. Instead, they are typically quite irregular, with sides of varying size and shape. Although some meteorites may develop a conical shape, most will not appear aerodynamic once they land. Although irregular in shape, most meteorites will have edges that are rounded rather than sharp. If the rock you’ve found is relatively normal in shape, or is round like a ball, it may still be a meteorite. However, the vast majority of meteorites are irregular in shape.

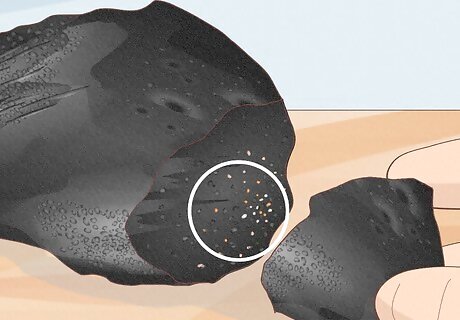

Determine whether the rock has a fusion crust. As rocks pass through the Earth’s atmosphere, their surfaces begin to melt and air pressure forces the molten material back, leaving a featureless, melt-like surface called a fusion crust. If your rock’s surface looks like it has melted and shifted, it may be a meteorite. A fusion crust will most likely be smooth and featureless, though it may also include ripple marks and “droplets” where molten stone had moved and resolidified. If your rock does not have a fusion crust, it is most likely not a meteorite. The fusion crust may look like a black eggshell coating the rock. Rocks in the desert will sometimes develop a shiny black exterior that looks similar to fusion crust. If you found your rock in a desert environment, consider whether its black surface might be desert varnish.

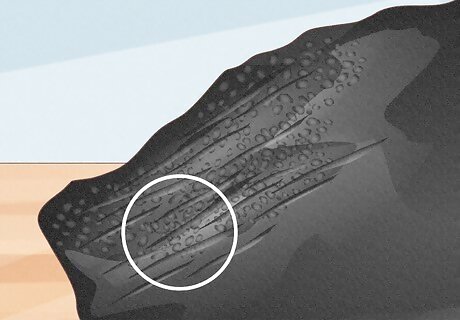

Check for flow lines where the surface may have melted. Flow lines are small streaks on the fusion crust from when the crust was molten and was forced backwards. If your rock has a crust-like surface with small streak lines across it, there’s a good chance it’s a meteorite. Flow lines may be small or not immediately apparent to the naked eye, as the lines can be broken or not completely straight. Use a magnifying glass and a discerning eye when looking for flow lines on the surface of a rock.

Identify any pits and depressions on the rock’s surface. Although the surface of a meteorite is generally featureless, it may also include shallow pits and deep cavities that resemble thumbprints. Look for these on your rock to determine both if it’s a meteorite and what type of meteorite it is. Iron meteorites are particularly susceptible to irregular melting and will have deeper, more defined cavities, whereas stony meteorites may have craters that are smooth like the rock’s surface. These indentations are technically known as “regmaglypts,” though most people who work with meteorites will suffice to call them “thumbprints.”

Make sure the rock isn’t porous or full of holes. Although craters and cavities on the surface may indicate that your rock is a meteorite, no meteorite has holes in its interior. Meteorites are dense pieces of solid rock; if the rock you’ve found is porous or bubbly in appearance, it’s unfortunately not a meteorite. If the rock you’ve found has holes in the surface, or appears “bubbly” as if it was once molten, it is definitely not a meteorite. Slag from industrial processes is often confused for meteorites, although slag has a porous surface. Other commonly mistaken types of rock include lava rocks and black limestone rocks. If you’re having trouble discerning between holes and regmaglypts, it may be useful to view side-by-side comparisons of these features online to learn how to spot the difference.

Testing the Rock’s Physical Properties

Calculate the rock’s density if it feels heavier than normal. Meteorites are solid pieces of rock that are usually densely packed with metal. If the rock you’ve found looks like a meteorite, compare it to other rocks to ensure it’s relatively heavy, then calculate its density to determine if it’s a meteorite. You can calculate the density of the potential meteorite by dividing its weight by its volume. If a rock has a calculated density higher than 3 units, it is much more likely to be a meteorite.

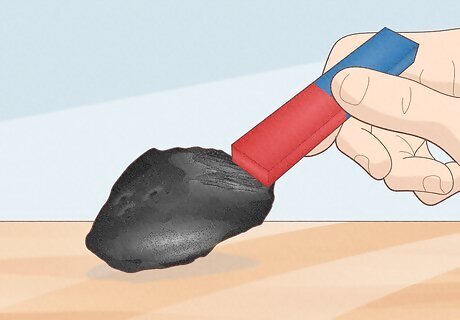

Use a magnet to see whether the rock is magnetic. Nearly all meteorites are at least somewhat magnetic, even if only weakly.This is due to the high concentration in most meteorites of iron and nickel, which are magnetic. If a magnet is not attracted to your rock, it’s almost certainly not a meteorite. Because many terrestrial rocks are also magnetic, the magnet test will not definitively prove your rock is a meteorite. However, failing to pass the magnet test is a very strong indication that your rock is probably not a meteorite. An iron meteorite will be much more magnetic than a stone meteorite and many will be strong enough to interfere with a compass held close to it.

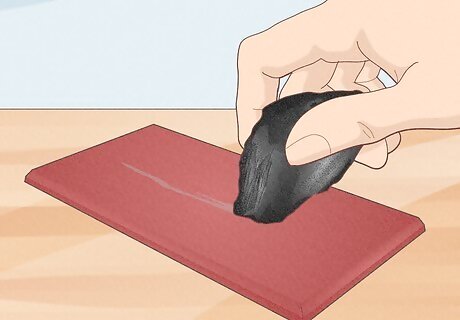

Scratch the rock against unglazed ceramic to see if it leaves a streak. A streak test is a good way to test your rock to rule out terrestrial materials. Scrape your rock against the unglazed side of a ceramic tile; if it leaves any streak other than a weak grayish one, it is not a meteorite. For an unglazed ceramic tile, you can use the unfinished bottom of a bathroom or kitchen tile, the unglazed bottom of a ceramic coffee mug, or the inside of a toilet tank cover. Hematite and magnetite rocks are commonly mistaken for meteorites. Hematite rocks leave a red streak, while magnetite rocks leave a dark gray streak, indicating that they are not meteorites. Keep in mind that many terrestrial rocks also do not leave streaks; thus, while the streak test can rule out hematite and magnetite, it will not definitively prove your rock is a meteorite on its own.

File the surface of the rock and look for shiny metal flakes. Most meteorites contain metal that is visibly shiny under the surface of the fusion crust. Use a diamond file to file a corner of the rock and check the interior for telltale metals on the inside. You’ll need a diamond file to ground down the surface of a meteorite. The filing process will also take some time and a good bit of effort. If you’re unable to do this on your own, you can take it into a laboratory for specialist testing. If the interior of the rock is plain, it is most likely not a meteorite.

Inspect the inside of the rock for small balls of stony material. Most meteorites that fall to Earth are of the type to have small round masses on the inside known as chondrules. These may look like smaller rocks and will vary in size, shape, and color. Although chondrules are generally located in the interiors of meteorites, weather erosion may cause them to be visible on the surface of meteorites that have been exposed to the elements for a sufficient amount of time. In most cases, you will need to break open the meteorite to check for chondrules.

Comments

0 comment