views

On June 17, the ministry of environment, forests and climate change celebrated World Day to Combat Desertification and Land Degradation at Vigyan Bhawan. On the ground, however, there is little to celebrate because the country’s fertile lands are turning into wastelands.

According to a 2016 report by ISRO’s Space Applications Centre, desertification is underway across 96.4 million hectares, totalling around 30 per cent of the country’s land area.

The report details observations for the period between 2011 and 2013.

Scientifically speaking, land degradation is the reduction or loss of biological or economic productivity of land because of natural and human-driven activities, according to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

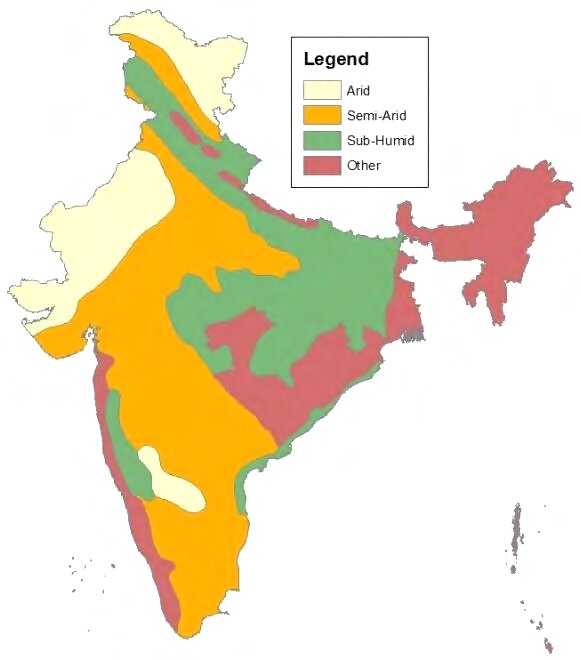

When such degradation occurs in drylands — arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas — it is referred to as desertification. It is important to note here that around 70 per cent of India falls under drylands.

About 80 per cent of degraded lands in the country lie in nine states — Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Telangana.

As for the status at state-level, more than 50 per cent of the total geographical area of Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Delhi, Gujarat and Goa is being degraded. And high desertification was observed in Delhi, Tripura, Nagaland, Himachal Pradesh and Mizoram.

Human Activity-driven Desertification

The three most dominant reasons for desertification in India are water erosion, vegetation degradation and wind erosion.

Water erosion that results in the erosion of top soil — the layer that is rich in plant nutrients and bacterial activity — because of rainfall and surface runoff water was responsible for about 11 per cent desertification in the country.

Vegetational degradation owing to activities such as deforestation arising from industrialisation and mining, shifting cultivation, overgrazing etc. contributed to about 9 per cent of overall desertification and wind erosion contributed to about 5.5 per cent.

Salinity, water logging, etc. are among other reasons for this process.

Most of the above reasons, though, are manmade and are largely resultant of changes in land use enabled by policy decisions adopted by successive governments.

To illustrate, a report by the Centre for Policy Research (CPR) states how environmental clearances were granted between 2005 and 2016 over lands that were previously designated as revenue grazing land, agricultural land or common use areas such as fishing harbours or river beds.

The clearances were for 12,44,736 hectares of land to projects from just four sectors — mining, thermal power, river valley and infrastructure.

“On the one hand, we have drawn out all the nutrients and pumped in chemicals and toxins through industrialised form of agriculture, production or transportation. And on the other hand, erosion of mountains and coasts is a result of policies that have cut, built over and drilled into these fragile ecosystems,” explained Kanchi Kohli, senior researcher at CPR.

Desertification and Water Crisis

When desertification takes its toll, India’s water crises are only expected to worsen. This happens because land degradation leads to the drying up of freshwater resources and increases the frequency of droughts.

More alarmingly, the trends continue in a vicious cycle. With the degradation of natural water resources, soil quality degrades and leads to the loss of vegetational cover. And all of this, in turn, causes desertification. And this cycle is already at play.

According to a report released by NITI Aayog in June, 2018, “India is suffering from the worst water crisis in its history.”

The report stated that 600 million in the country are facing “high to extreme water stress” and that “about two lakh people die every year due to inadequate access to safe water.”

As for future predictions, the report noted that by 2030, the country’s water demand is projected to be twice the available supply. And the eventual cost of such a disaster would be about 6 per cent of the country’s GDP.

The Path Ahead

This September, India will host the 14th session of the Conference of Parties (COP-14) of the UNCCD, of which India is a signatory.

Ahead of the session, the MoEFCC has suggested that it would launch the pilot version of a project aimed at enhancing the capacity of forest landscape restoration (FLR) across Haryana, MP, Maharashtra and Nagaland over a period of 3.5 years.

Forested landscapes preserve the water cycle, moderate soil erosion and protect biodiversity. They are key, therefore, in slowing down desertification processes.

The project is in partnership with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and is part of a larger global initiative called the Bonn Challenge to bring 150 million hectares of the world’s deforested and degraded land under restoration by 2020, and 350 million hectares by 2030.

For its part, India has pledged to restore 13 million hectares of degraded and deforested land by 2020, and another 8 million hectares by 2030.

But it should be noted that restoration plans are merely reactive in nature.

“The enhancement of forest landscapes should not be limited to encouraging plantations,” Kohli said. “Proactive and preventive steps are needed to secure these areas from land use change for mining, infrastructure and industrial uses along with encouraging inclusive conservation practices.”

Comments

0 comment