views

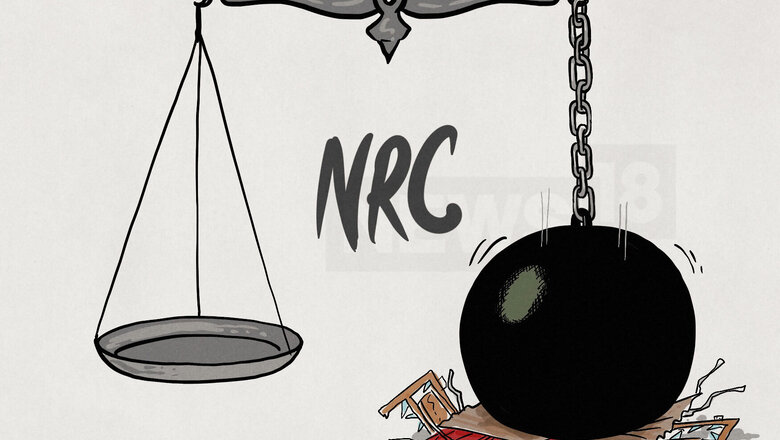

Guwahati: A controversial citizenship list in northeast India that has left almost two million people facing statelessness has been slammed by its political backers as those excluded from it face an uncertain future.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, which runs Assam state where the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was collated, pushed for the list saying it was necessary to detect "foreign infiltrators".

Critics said the NRC process reflected the BJP's goal to serve Hindus, with a large chunk of those excluded expected to be Muslims.

But the strategy appears to have backfired with local BJP leaders claiming that many Bengali-speaking Hindus, a key vote bank for the party, were left off the list.

"We do not trust this NRC. We are very unhappy," Ranjeet Kumar Dass, BJP party president in Assam told the Press Trust of India late Saturday.

"Many people with forged certificates were included," Dass said, while 200,000 "genuine Indians" were left out.

Those left off have 120 days to appeal at special Foreigners Tribunals.

"If we see that FTs are delivering adverse judgements on the appeals by genuine Indian citizens... we will bring in legislation and make an act to protect them," Dass added.

Some 100,000 Gorkhas, who speak Bengali, were also excluded from the list, West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee tweeted Sunday as she called the NRC a "fiasco".

A leader of the main opposition Congress party Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury said his party would support those who were wrongly excluded, including providing them with legal aid.

UN stateless fears

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi on Sunday called on the government to refrain from detaining or deporting anyone whose nationality is not verified through the process.

"Any process that could leave large numbers of people without a nationality would be an enormous blow to global efforts to eradicate statelessness," Grandi added in a statement.

Assam has long seen large influxes from elsewhere, including under British colonial rule and around Bangladesh's 1971 war of independence when millions fled into India.

Under the NRC, only those who could demonstrate they or their forebears were in India before 1971 could be included in the list.

Assam villagers told AFP about family members who were excluded even though they had similar documents to their relatives.

"Our children's names are in the list but my wife's name is missing. She submitted all the documents and records... Why?," asked resident Jaynal Abudin.

Those left out, many of whom are poor and illiterate, have to navigate a long and expensive legal process that could include bringing their cases to the courts if they are rejected by a foreigner tribunal.

People rejected by the tribunals who have exhausted all other legal avenues can be declared foreigners and -- in theory -- be placed in one of six detention centres with a view to possible deportation.

The camps currently hold 1,135 people, according to the state government, and have been operating for years.

A senior government official told The Hindu on Sunday that it was not "practical" to send a large number of people excluded from the list to detention camps.

"No decision has been taken about the people who will be declared foreigners, maybe they are given work permits," the official, who was not named, told the newspaper.

The NRC, which comes in the wake of New Delhi revoking the autonomy of Kashmir, India's only Muslim-majority state, has reinforced fears among India's 170 million Muslim minority that they are being singled out by the central government.

The BJP has previously said it wants the NRC to be replicated nationwide, with Dass echoing similar sentiments on Saturday.

Comments

0 comment