views

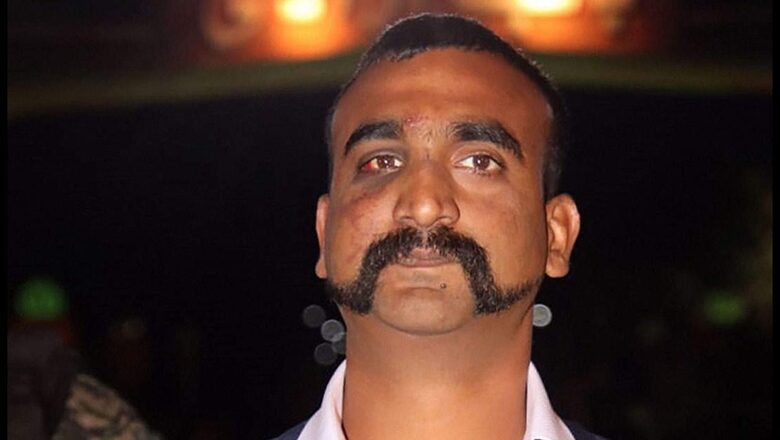

Former Indian high commissioner to Pakistan Ajay Bisaria was on duty during a relatively short but particularly tumultuous period of New Delhi-Islamabad ties. He has just come out with a book on his experience, titled ‘Anger Management: The troubled diplomatic relationship between India and Pakistan’. Speaking with CNN-News18, he shared riveting details about how the ‘homecoming’ of Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman became a reality and a panic-stricken Pakistan’s reaction to the Indian government withdrawing Kashmir’s special status. Edited excerpts:

The most compelling part of your book, where you talk about your time in Pakistan, it was quite an eventful time. We had the Pulwama attack, the Balakot airstrikes, and of course, culminating with the abrogation of Article 370. I want to start by asking you about the events of February 27 (2019). That was the day of the Balakot airstrikes, there was a tense atmosphere between Islamabad and New Delhi. When did you first get news about the capture of Indian Air Force pilot Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman and what were the conversations like in the immediate aftermath?

Initially on February 27, there was much by way of fog of war. There wasn’t clarity on what was happening. There was news that three parachutes had dropped in Pakistan with three Indians. Later it was reported that only one of them was Indian and the other Pakistanis. Only in the evening, it was clear that an Indian pilot was in Pakistani custody and it was soon confirmed by videos floating on WhatsApp from Pakistan that the pilot Abhinandan was in Pakistani custody. I think that’s where the dynamics of the operation changed.

On the night of the 27th, you got a call from your Pakistani counterpart seeking a phone call between the leadership in Pakistan and the leadership in India. What did you do?

I received a call at midnight. It had been a long day. I got this call from my counterpart, the Pakistani high commissioner to India, who was then in Islamabad, saying that prime minister Imran Khan wanted to speak to prime minister Modi. He didn’t specify what it was about but we both possibly guessed it. I checked and got back to him and said the prime minister is not available but if you have any specific message, please pass it on to me and I will convey it to the prime minister. I did not get a call back on that, so one can only guess what it was about.

When did you get the sense that the Indian leadership was willing to escalate this if something were to happen to Wing Commander Varthaman?

There were multiple conversations that had started in different capitals and in Delhi with various foreign diplomats, making the point to them that India’s ask was that the pilot be returned, or India could escalate the situation. This message was sent loud and clear across the world, and the message also went to Pakistan. Later Pakistan revealed to foreign diplomats and the Indian diplomatic representative, the acting high commissioner, that it had information about nine missiles that India had pointed towards Pakistan, and that it felt it was a dangerous escalation that India should refrain from. And India’s position was clear that the pilot should be returned according to international law by a certain deadline or India would escalate.

What were the conversations that were happening at that time?

There were conversations taking place at multiple levels. My brief was to negotiate with Pakistan and get the pilot home…We had an example, or precedent, of the return of another pilot, Nachiketa, during the Kargil conflict, who was returned to India after a few weeks, but not before some grandstanding by Pakistan, wanting to show it to the media and so on. So we had this precedent and we had started these conversations to get the pilot back. And there was a lot of conversation going on about the need to escalate the situation in case Pakistan did not play ball. Because in Pakistan there were some conversations even in the public domain that they should keep the pilot and negotiate with India or get some benefit out of it.

Publicly we got to know when Pakistan prime minister Imran Khan told the parliament that they were releasing Wing Commander Varthaman as a goodwill gesture. But your account suggests that they were scared India would escalate.

We had advanced intimation of the possibility from different sources. We were told that this is what Imran Khan would say. He would talk about abjuring terrorism and returning the pilot. And that is exactly what we were expecting in that speech. But until that speech happened, we were not sure that Pakistan would in fact make that statement.

How were the intervening hours for you and your team?

The situation was tense and given that with Pakistan, there was an absence of trust. Even after that speech, it wasn’t clear what would happen. One deadline was missed; he was supposed to be in by 5pm at Wagah-Attari but it was close to 9pm when he came. So I think the feeling was that until the man is home he isn’t home. We had quite a few tense moments. I was on the phone continuously with our then defence minister Nirmala Sitharaman, and she was anxious to know what exactly was happening. My air attache was escorting him and they were trying to figure out what was happening. I think it all ended well, but it certainly was a success of India’s coercive diplomacy.

It was in May or June of 2019 when a message was sent from the highest military leadership of Pakistan about an impending terror attack in Kashmir, which was then foiled. Did you get the impression that COAS Bajwa wanted to mend fences with India, perhaps for pragmatic reasons?

There were signs that something was changing and we were watching carefully and analysing. Certainly, this move of sharing a piece of intelligence and escalating it to a political level, and calling me up and telling me that this was something Pakistan was going to do was both a message to India about some change in behaviour but also a message that Pakistan did not want another Pulwama even by accident.

Were the Pakistanis completely taken by surprise when Article 370 sections were abrogated?

I was in Islamabad then, and through August, Pakistan was seeing signs and getting worried that there were a large number of troops in Kashmir valley, the Amarnath being called off…But essentially Pakistan was caught by surprise. It shouldn’t have been because it was in the manifesto of the BJP and should have been anticipated. And they were repeatedly summoning foreign diplomats, telling them that India was up to something…When the Indian parliament took that decision on the 5th of August, I had some inkling because I had visited India a little earlier, but it caught Pakistan by surprise, and the evidence of that is the way the policymakers scrambled in panic immediately in the aftermath.

Did they summon you and did you have any conversations with your Pakistani counterparts?

On the 5th of August, I was summoned. First, the Western ambassadors were summoned. And they said why don’t you speak to the Indian high commissioner, he is a nice guy, he’ll pass the message back home. As a result at 6pm that day. I was called in by the foreign secretary, who was by then my former counterpart, Sohail Mehmood for a strong demarche and talking about India’s siege of Kashmir and so on, and I had to push back at the meeting and say that Pakistan had no role in this internal matter that India had decided. At that time there was no inkling that I would be asked to leave. That happened a couple of days later, when some members of parliament stood up and said that the Indian high commission should be closed and the high commissioner sent back, and that’s what eventually happened.

What is your view on the road ahead, particularly with elections in Pakistan next month?

I would be cautiously optimistic about the scenario because, in this snakes and ladders game in the India-Pakistan scenario, a new election is definitely a ladder. It means a new government, new thinking, particularly if it is Nawaz Sharif, who is in the mix. With elections in India, I think a window of opportunity would open up if we go without any major terrorism in the period and there could be the right conditions for a perfect storm to talk to each other.

You’ve had a ringside view, particularly in the last few years of the Modi government’s Pakistan policy. How would you assess it?

I think it’s been a pragmatic and realistic handling of the situation. This terrorism conundrum had been with us for over three decades and we didn’t really find the vocabulary and instruments to deal with the sub-conventional and proxy warfare in a persuasive way that would dissuade Pakistan. I think finally we have in the last decade found the answer of being able to deal in a subconventional space with terrorism without worrying about escalation to a conventional level but being prepared for it. And that is exactly what we feel that an answer can be given to terrorism at a sub-conventional level and the cost that we could inflict on Pakistan and its establishment using this instrument. Can we heighten it to such an extent that it becomes a strong disincentive to deploy this instrument in the future? Hopefully, we will continue to move in that direction and Pakistan will see the light of reason and normalise itself, because it does not serve Pakistan’s own interest to use this instrument.

Comments

0 comment