views

Defence minister Khawaja Asif has said that Pakistan has already defaulted amid looming fears that the cash-starved country may go bankrupt and blamed the establishment, bureaucracy and politicians for the prevailing economic crisis. Addressing a ceremony in his home town of Sialkot, he said that standing on its own feet was crucial for Pakistan to stabilise itself.

“You must have heard that Pakistan is going bankrupt or that a default or meltdown is taking place. It (default) has already taken place. We are living in a bankrupt country,” he was quoted as saying by The Express Tribune newspaper.

“The solution to our problems lies within the country. The IMF does not have the solution to Pakistan’s problems,” he said. He said that everyone, including the establishment, bureaucracy and politicians, are to blame for the current economic mess as the law and Constitution are not followed in Pakistan.

But What Has Happened in Pakistan and Why is the Country Facing Such a Dire Economic Situation?

Explained in 10 Points

- Years of financial mismanagement and political instability have damaged Pakistan’s economy — exacerbated by a global energy crisis and devastating floods that submerged a third of the country.

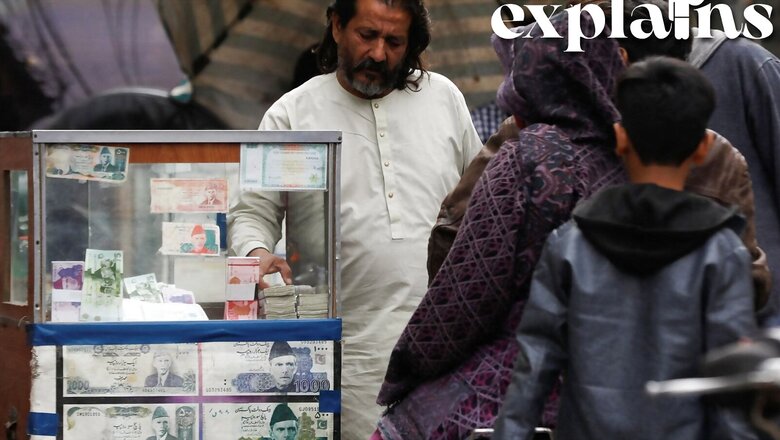

- Alongside a shortage of raw materials, soaring inflation, rising fuel costs and a plummeting rupee have battered manufacturing industries.

- An IMF delegation left Pakistan on Friday after urgent talks to revive a stalled loan programme ended with no deal, leaving lingering uncertainty for business leaders.

- According to Geo News, Pakistan raised the price of fuel to Pakistani Rupees (Rs) 272 per litre and gas on Wednesday in order to please the IMF and unlock the vital loan tranche. The price of high-speed diesel has risen by 17.20 cents to 280 cents a litre. Following a 12.90 increase, kerosene oil will now cost 202.73 per litre. Likewise, light diesel oil will cost Rs196.68 per litre, a 9.68 percent rise.

- The Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM)-led federal government hoped that the “mini-budget” would help to lower the budget deficit and broaden the revenue collecting net. According to the mini budget, the general sales tax has been raised from 17 percent to 18 percent. The minimum cigarette price: No brand shall be priced and sold at a retail price (excluding sales tax) less than 60% (formerly 45%) of the retail price. The price of kerosene oil has increased by $12.90 to 202.73 per litre, up from 189.83, said a report by Mint.

- Fitch has previously reduced the country’s long-term foreign currency issuer default rating (IDR) to ‘CCC-‘ from ‘CCC’ on 14 February, citing continued deterioration in liquidity and policy risks. The downgrade reflected a significant worsening in external liquidity and funding conditions, as well as a drop in foreign currency (FX) reserves to “critically low levels,” according to Fitch.

- According to Reuters, a senior economist at Moody’s Analytics, inflation in Pakistan could average 33 percent in the first half of 2023 before falling lower, and a bailout from the International Monetary Fund alone is unlikely to get the economy back on track.

- Pakistan’s reserves have slipped below $3 billion, and the government is on the verge of defaulting on its external payments unless the IMF releases funding.

- The availability of IMF funds will prevent a default, but it is expected to cause a wave of price increases. Pakistan signed a $6 billion IMF programme in 2019, which was increased to $7 billion last year. Pakistan is on its 13th IMF bailout since the late 1980s.

- Owing to the unpredictability of its economy and its reliance on imports, the IMF has made twenty-two loans to Pakistan, the most recent in 2019.

Why Has Pakistan Kept Borrowing

In a 2015 Columbia University research, economist Akbar Noman stated that Pakistan had one of the world’s ten fastest expanding economies between 1960 and 1990. He also claimed that “the seeds for the future economic and technological malaise were sowed” during this time period.

“Despite the external shocks of the 1965 conflict with India, the 1971 war and the country’s disintegration, as well as the “policy shocks” that followed in its wake,” Noman explained, according to a report by ThePrint.

However, the 1970s was also marred with disruptions resulting from war and the break-up of the country, combined with ill-conceived populist policies and nationalisation, Noman noted.

“While much of that was reversed in the 1980s, the decade was one of facile growth and one in which a different set of seeds was sown for the subsequent slowdown,” he said.

During the 1980s, the set of bad seeds alluded to the “heavy domestic borrowing at very high interest rates that allowed unsustainably expansionary fiscal policies in the 1980s and that were at the heart of the macroeconomic crises and consequent austerity programs – with a series of IMF bailouts – that have shackled growth since the early 1990s.”

Noman went on to say that the emergence of the politics-governance-security nexus, deterioration in the security situation, growth of terrorism coupled with worsening foreign attitudes, business sentiments, and increasing cost of doing business all contributed to the ongoing downturn.

Norman added that even in the zenith of its growth performance, Pakistan grossly underinvested in human development. This underinvestment contrasted sharply with East Asian economies that maintained strong economic growth and transformation, and no doubt contributed to Pakistan’s inability to do so.

Read all the Latest Explainers here

Comments

0 comment