views

The highlight of the recently held Assembly elections in Bengal and Assam was the utilisation of polarisation with varied success in the campaigns. The political campaigns in both the states were marked by divisive rhetoric, a heady mix of religion and identity politics, and political violence. However, with both states having enabling conditions for polarisation viz. presence of a substantial minority population, long history of illegal migration/refugees from across the border, slow burning identity issues and communal conflicts—all eyes were on the efficacy of polarisation as a key campaign tool.

It may be noted that polarisation, which can occur on multiple axes (religious, ideological, ethnic, societal), is a common feature in most democracies. Often rooted in long-existing divisions in society, it is widely used by parties, political actors, and even campaign management agencies to gain electoral windfalls. The world was witness to how former President Donald Trump used polarised rhetoric to make unprecedented political gains in 2016 and the UK’s Brexit campaign was largely facilitated by the use of polarisation. One has seen similar churns in other major democracies, particularly Brazil, Turkey, Poland, Indonesia, and India, amongst others.

In India, polarisation as a tool has been deployed by most political parties all through the years since Independence; for instance, the Indian National Congress’ Indira Gandhi deftly used ‘politics of crisis’ to divide voters. However, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has risen over the last few decades through the deft use of political polarisation. From a nearly non-existent presence in Parliament in 1984, it emerged as the second largest party in 1991 largely on the weight of religious polarisation. The Ram Janmabhoomi movement and L.K. Advani’s rathyatra (chariot procession) largely powered the party’s phenomenal rise, helping it to form governments in 1996, 1998 and 1999. For many analysts, the BJP’s unprecedented comeback in 2014, winning a full majority on its own, was, to some extent, achieved by the deployment of polarisation to effect Hindu consolidation in the Hindi heartland states.

Many analysts credit the BJP’s unprecedented electoral victory in Uttar Pradesh (UP) in 2017 to the party’s successful consolidation of Hindu votes. The clearest evidence of this was the lacklustre performances by the then ruling Samajwadi Party (SP) and the once dominant Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). Their traditional vote banks (except the Yadav and Yatav castes) deserted for the BJP. The SP lost all four seats in its traditional stronghold of Etah.

The Bengal Case

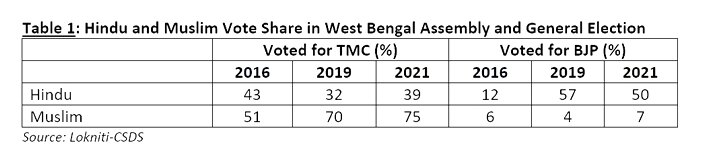

The BJP had hoped to re-enact the UP performance in the Bengal Assembly elections this year. This was due to the party’s stunning performance in Bengal in the 2019 general elections. From a mere two Lok Sabha seats in 2014, its tally soared to 18 seats apart from capturing as much as 40 per cent of the vote share in the state. What was significant in the 2019 results was that the BJP was able to pocket as much as 57 per cent (see Table 1) of the Hindu community vote.

While the BJP made relentless efforts to reach out to diverse constituencies, particularly those disgruntled by the Trinamool Congress (TMC), the instrument it sought to deploy to secure a sensational victory was its proven tool—polarisation. Building on the playbook it had used in other states with mixed success, the party heavily invested in displaying Hindu assertion, with the celebration of Ram Navami and Hanuman Jayanti, and with several outfits being mobilised to spread the message of Hindutva. What helped them in their mission was Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s perceived Muslim ‘appeasement’ policies, such as providing special grants to Islamic clerics and her party siding with the Muslim orthodoxy on the issue of Triple Talaq.

The narrative of Muslim appeasement by TMC became so embedded that the welfare policies and public goods of the TMC government were perceived to be in favour of Muslims while jeopardising the interest of the Hindu majority. Taking it a step further, the BJP promised the implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in the state to grant permanent citizenship to the electorally important Hindu Dalit population. This seemed to have worked both in 2019 as well this election for the BJP, as the party did well in the international border districts.

Once the Assembly election dates were announced, the BJP sharpened its polarising tools to aggressively mobilise votes along religious and ethnic lines. So much so that the Prime Minister used foreign shores (Bangladesh) to run a Matua Hindus outreach in March. Similarly, the BJP tried to invoke the fear that TMC would eventually make the state ‘West Bangladesh’ and often addressed Mamata as ‘Begum’. Of course, the TMC launched a blistering counter attack against the BJP, painting it an “outsider” and a major threat to Bengali culture. Mamata tried to display her Hindu-ness by adopting ‘soft Hindutva’ tactics like visiting temples and chanting rhymes. In short, this was an overtly polarised election campaign.

Yet, the BJP did not manage to come to power in Bengal. Not only did the party fail to cross even 100 seats, its vote share was pared down to 38 per cent against the TMC breaking all its past records with a 48 per cent vote share. The Hindu consolidation that the party had achieved in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls melted away in the Assembly polls. According to the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) post-poll survey data (See Table 2), while the BJP had received as many as 57 per cent of the Hindu vote in 2019, it declined to 50 per cent in 2021. According to the survey, a fall in seven per cent Hindu vote share and an overwhelming support of Muslim voters (who constitute little above 30 per cent of the total population) for TMC stopped the saffron juggernaut in Bengal.

Why didn’t polarisation pay off in the assembly elections? According to some analysts, the effects of polarisation were greatly defused by a combination of factors such as Mamata’s continued popularity despite corruption charges, with welfare schemes, women voters backing the TMC, the devastation of the second wave of COVID-19, and the BJP’s lack of a credible local face giving the TMC the edge. In addition, the TMC’s aggressive campaign exhorting Bengali asmita (cultural pride) and the narrative of the BJP being “outsiders” seemed to have played key roles in securing Mamata a massive third term.

The question to be asked, however, is, “Was polarisation a decisive factor in the Bengal elections, notwithstanding the voluble debate on “Subaltern Hindutva” and the BJP’s phenomenal rise in this crucial eastern state?” For a more conclusive answer, let us take a glance at the core voters of the BJP in 2019 and 2021 and see whether they rallied behind the party for Hindutva appeal or for other reasons.

There is enough evidence to suggest that the BJP, which rules at the Centre and has an overwhelming presence in the country including the eastern region, was viewed as the real challenger to the incumbent TMC. Some analysts credit this to the mass exodus of the supporters of the Left and the Congress to the BJP after the 2018 panchayat elections, which witnessed unprecedented levels of violence by TMC supporters, which many believe led to the TMC wining as many as one-third of the seats unopposed.

In addition, factors like the TMC’s mishandling of cyclone Amphan and corruption charges in the implementation of welfare schemes (cut money) pushed many voters towards the BJP. The clearest proof can be found in the performances of various parties in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls. While the BJP dramatically improved its vote share to 40.25 per cent capturing as many as 18 seats, the once dominant Left coalition could not open its account. The Congress was able to win only two seats.

In short, it was not polarisation and consolidation of Hindu voters that made the BJP emerge as the main challenger to the TMC. Prime Minister Modi’s popularity, the party’s massive rural outreach and its attractiveness as an effective counterforce to the TMC turned the tables in favour of the BJP in the national elections. However, in Assembly elections, voters look for a credible local face, the incumbent party’s record in delivering public goods, and other local-specific narratives. Bengal’s election results largely supports the national trend of incumbent state parties losing out to national parties (in seats and vote shares) in national elections, but effectively holding out against the national parties in assembly elections. Good examples of this duality are Delhi’s Arvind Kejriwal and Odisha’s Naveen Patnaik.

BJP’s ‘Effective’ Polarisation in Assam?

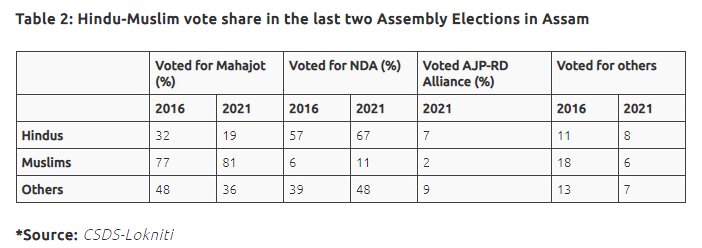

In Assam, the BJP managed two back-to-back Assembly election victories. This has prompted some analysts to link the party’s success in Assam to the effective deployment of polarisation, effecting a larger Hindu consolidation. Though the dominant theme in Assam politics has been illegal immigration from Bangladesh, in the wake of the NRC (National Register of Citizens) and CAA controversies, the BJP was facing serious backlash as ‘indigenous communities’ were opposed to these moves. However, analysts believe the party successfully turned this ‘native versus outsider’ regional political discourse into a religious one to its advantage. The BJP-led coalition effectively succeeded in projecting the Bengali-speaking Muslim immigrants as the ‘threat’ while accommodating the Hindu Bengali migrant population in its Hindutva fold. The BJP changed its earlier strategy by calling for the ‘correction’ of the existing NRC list as it reportedly excluded a sizeable section of Hindus.

According to commentators, the high point of the polarisation in Assam was that unlike the TMC, which did not tie up with any religious- or minority- affiliated party, the Congress Party had forged an alliance with Badruddin Ajmal’s All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF). The BJP launched blistering attacks against the Congress-led grand coalition, especially targeting Ajmal’s identity and Bangladesh connections. The BJP criticised the coalition for allegedly protecting Bangladeshi Muslims in its fold against the interest of Assamese Hindus. The BJP’s campaign warned the Hindu Assamese that the grand coalition would work only for the 35 per cent Muslim population, referring to the Muslim populace in the state as a “civilisational” conflict and called Miyas or Bengali Muslim migrants a “threat to Assamese people”. However, the most distinct aspect of BJP’s polarisation tactics was the relentless attacks on AIUDF chief Ajmal, his “attire, skull cap, and beard”.

Analysts believe polarisation and Hindutva brought a rich dividend for the BJP coalition as it performed very well in Upper Assam, dominated by Assamese Hindus. The party retained power with a comfortable 75 seats in the 126-seat house. The AIUDF also benefitted from the polarisation by bagging 16 out of 20 seats, while the biggest loser in the game was the Congress, which, for a while, appeared to be a strong contender to unseat the ruling BJP.

Yet, the moot question is—was it only polarisation and the aggregation of Hindu votes which propelled the BJP’s historic back-to-back win in Assam or are there more compelling factors that shaped its victory? A deep dive into available evidence tells a different story. While polarisation did help the BJP in Upper Assam, in other regions of the state, the party encashed on a combination of factors: Welfare schemes and hyper populism as well as strong and credible local faces, particularly the BJP’s (the Congress lacked this) go-to man Himanta Biswa Sarma putting up an effective campaign and stitching up useful coalitions helped the party escape the uncertainty created by anti-CAA sentiments. The party was quick to make exemption for three Sixth Schedule council areas—Bodo Territorial Council (BTC), Karbi Autonomous Council, and the Dima Hasao—from the jurisdictions of the CAA. Finally, the BJP encashed on its developmental records by unleashing hyper populist schemes such as Urunodai (to woo the tea tribes), and the Arogya Nidhi scheme, among others.

Conclusion

The Assembly elections results in two neighbouring states—Bengal and Assam—offer plenty of takeaways for those interested in exploring the potentials and limits of polarisation as a potent campaign tool. While both Bengal and Assam provide fertile grounds for polarisation, the election results in both states were vastly different. The BJP, which had greatly benefitted by deploying polarisation tools to capture power in Assam in 2016, had to reinvent and marshal other critical tools to retain power in 2021. Polarised rhetoric was decisively blunted in Bengal in the face of a credible local challenger and a host of other factors dominating the competitive electoral spaces. This brings one to conclude that polarisation may work in states like UP, but it does not necessarily work in Bengal even when similar enabling conditions exist. Moreover, polarisation has a diminishing return as the case of Assam has exemplified.

This article was first published on ORF.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment