views

Rivers are in a state of peril. The veins and arteries of the planet have been clogged, impounded, and polluted, much of their roles defined by and for human interests. According to a recent estimate of the connectivity status of 12 million kilometres of rivers in all the continents excepts Antarctica, only 37 per cent of rivers longer than 1,000 kilometres remain free-flowing. For the rest of them, their ecosystem functions and services have been impacted to varying degrees through the creation of dams, embankments, etc. These hinder the exchange of water, energy, material, and biota between the stretches of a river, and the exchanges with the landscape. Despite a suite of environmental laws that have been in existence globally, the harm to riverine ecosystems has continued unfettered.

A possible reason for the weakness in existing legal safeguards is that legal systems treat nature as a property that can be exploited, thereby, creating a false dogma of humans over nature and undermining the interconnectedness shared by the two. Often an ‘environmental threshold’ is put forward to operationalise these laws thereby legalising environmental harms to a certain degree and discounting the net destruction of the natural world. Further, the regulatory mechanisms that ensure compliance to established protocols in developing countries like India have remained weak. In such a scenario, the emerging environmental jurisprudence of granting a legal ‘personhood’ to rivers differs from the long-established treatment of rivers as passive objects requiring protection. Instead, it actively empowers them in a way that they can actively participate in litigations for protecting themselves!

Separate Pathways, Same Intent

The first instance of recognising legal rights can be traced to the Sierra Club v. Morton case (1972) in the United States of America. In this case, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas had issued the famous dissenting opinion: “Contemporary public concern for protecting nature’s ecological equilibrium should lead to the conferral of standing upon environmental objects to sue for their own preservation.”

ALSO READ | Mere Laws Not Enough to Protect Ecosystem. We Must Tap Traditional Knowledge of Communities

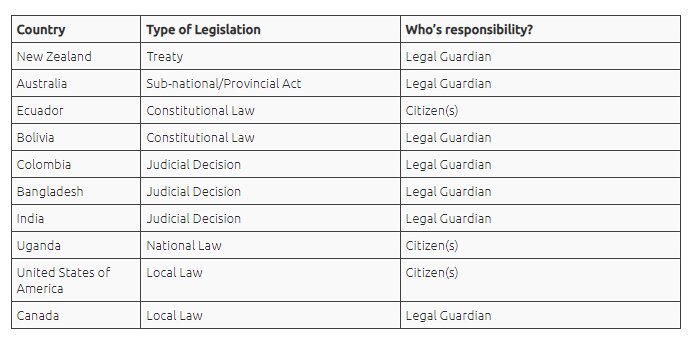

Since then, sources of freshwater like rivers, wetlands, aquifers, etc. have emerged as the frontrunner in the claim for legal personhood. Legislations have emerged through a wide variety of mechanisms and at different jurisdictional scales—ranging from a river basin-specific treaty or a region-specific ordinance to a nationwide constitutional law. Furthermore, two distinct pathways for operationalising the rights-based framework exist. One requires the creation of a legal guardian for safeguarding the interests of the river while the other requires the courts to uphold the rights through the active involvement of the community. Despite the divergence, the objective remains the same—to protect the river from degradation while adopting an eco-centric approach as against an anthropocentric one and keeping the river’s interest at the core.

Piecemeal Approach, Limited Success

In the endeavour to confer legal rights, little attention has been paid to the connections that define river systems. Despite an iteration of law-making from an eco-centric perspective, legislations have not taken into account the interactive pathways between rivers with the surrounding landscape. The considerations for legal personhood have often been restricted to the visible channels, thereby, undermining the interconnected processes that nourish and sustain the various types of ecosystems along the river and in the riparian zones.

For example, in the case of the Vilcabamba River in Ecuador, the local government allowed the dumping of rocks and excavation materials into the river to widen the road and improve access to the ‘Valley of Longevity’. The court gave its verdict by invoking nature’s rights under Article 71 of the Constitution by making it obligatory for the authority to not dump the rubble into the river. However, it also allowed for the widening of the road, permitting the government to remove trees that constituted the riparian vegetation. Similarly, in the case of the Ganga River in India, the court had initially disregarded the scope of legal personhood to other connected elements. It took another Public Interest Litigation for the court to bundle the legal personhood of the river with that of all other natural objects including its glaciers.

Going forward, it is important to realise that rivers are not just connected to the glaciers that feed them but also elements of an interconnected system like floodplains, aquifers, riparian vegetation, catchments, the atmosphere and even the seas. Water acts as a conduit for the exchange of sediments, nutrients, and biota, thereby, creating complex and dependent ecological processes. As such, four interactive pathways exist—lateral (river-floodplain), longitudinal (across different river stretches), vertical (surface water–groundwater interaction) and temporal (biocomplexity of riverscapes, created over time). Thus, the extent to which the right of the river can be established needs to be backed by scientific assessments. The concept of river connectivity and exchange pathways can be an initial starting point.

Fixing the Scale

Closely related to the discussion in the previous section, assigning legal personhood to rivers is meaningless unless the river system is treated as a whole. The limitations of the legislations in terms of their territorial jurisdiction have meant that river systems have been traditionally reduced to manageable units. Institutions for their governance have followed suit. With conferring legal rights, this also appears to be a critical bottleneck in the case of large rivers that cross provincial and international boundaries.

For example, in the landmark judgments of the Uttarakhand High Court (UHC) that extended the legal personhood to the Ganga, the Yamuna, their tributaries and all other natural objects, the verdict faced flak when the Uttarakhand government appealed to the Supreme Court of India. In its appeal, representatives of the government cited their inability to act since the regulation of interstate rivers is guided by the Union government and the state government has no role to play. In fact, the Ganga and its tributaries do not just cross state boundaries but also cross international borders!

Thus, reducing the river to manageable stretches that conform with territorial jurisdictions of law, as has been the unintentional but inevitable consequence of different verdicts, is reductionistic and directly conflicts with the foundational principles of the eco-centric approach to law-making. At the same time, basin-level legislations for large rivers are a far cry when riparian nations don’t even have cooperative mechanisms and institutions for integrated management at the basin level. Perhaps, global conventions could be a possible route to overcome this hurdle.

As an initial step towards this, a coalition of relevant stakeholders has identified six fundamental values that describe the basic rights and serve as a legislative starting point for governments willing to pursue legal recognition of the rights of rivers. Popularly known as the Universal Declaration of River Rights, these are –

1. The right to flow.

2. The right to perform essential functions within its ecosystem.

3. The right to be free from pollution.

4. The right to feed and be fed by sustainable aquifers.

5. The right to native biodiversity.

6. The right to restoration.

ALSO READ | Wildlife Conservation Must Start with Planting Trees, Rebuilding Destroyed Habitats

Sustaining the Movement

Earth jurisprudence as a philosophy and practice of law and governance tries to reverse the prevalent approach of considering nature as an object of law to a subject of the law. This would necessitate establishing a reciprocal relationship between the river and people such that humans continue to derive benefits that do not cause irreversible damage to the river’s flow, the flora and fauna dependent on its flow and various elements of the landscape through which it flows. This would essentially translate to forgoing current benefits that humans derive from rivers through the construction of dams, embankments, water diversions, etc.

Therefore, the larger question that arises from this discussion is whether human society is even ready for such a transition. Ever since the dawn of the industrial age, human societies have looked to engineer nature to suit their interests. The scarcity and abundance of water—both challenges in the path of neoclassical growth—have been vanquished through the use of hydraulic control on flows. A reversal of this long-standing human culture would need much more than legislations that confer legal rights to rivers. For this rights-based framework to be more than a mere pushback with token results, it needs to be synchronised with ideas like sustainable development and nature-based solutions.

The incredible and truly transformative potential of conferring legal rights to rivers would be left unrealised if verdicts are delivered recklessly and laws reveal ambiguities. Caution needs to be exercised to prevent juxtaposing rivers for humans and arguing for rights akin to human rights. Most importantly, the steady growth of scholarship must keep pace with increasing activism for the movement to be anchored on firm ground while acquiring the punch to leave a lasting impact.

This article was first published on ORF.

The author is Junior Fellow at ORF’s Kolkata centre. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest News , Breaking News and IPL 2022 Live Updates here.

Comments

0 comment