views

If the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, the legal and culture wars over abortion that have consumed the United States for decades would increasingly shift to a new front: the use of abortion pills.

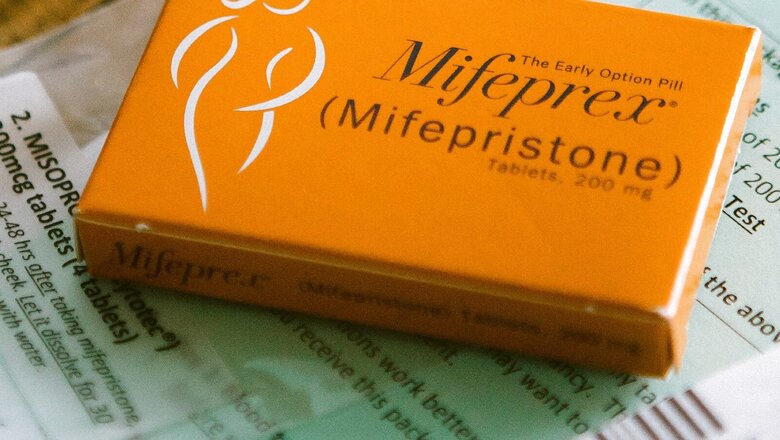

Medication abortion — a two-drug combination that can be taken at home or in any location and is authorized for use in the first 10 weeks of pregnancy — has become more and more prevalent and now accounts for more than half of recent abortions in the United States. If the federal guarantee of abortion rights disappears, medication abortion would likely become an even more sought-after method for terminating a pregnancy — and the focus of battles between states that ban abortion and those that continue to allow it.

“Given that most abortions are early and medication abortion is harder to trace and already kind of becoming the majority or preferred method, it’s going to be a big deal,” said Mary Ziegler, a legal scholar who has written widely on abortion. “It’s going to generate a lot of forthcoming legal conflicts because it’s just going to be a way that state borders are going to become less relevant.”

About half the states are expected to quickly make all methods of abortion illegal if the justices’ decision in a Mississippi case resembles a draft opinion leaked this week that would nullify the 1973 ruling that legalized abortion. In Louisiana, a legislative committee this week advanced a bill that would allow homicide charges to be brought against people who get abortions or perform them.

Other states would likely continue to allow abortion, and several are already taking steps to accommodate patients from the states where abortion may be outlawed.

Medication abortion is less expensive and less invasive than surgical abortions. In December, the Food and Drug Administration made access to it significantly easier by lifting the requirement that patients obtain the first of the two pills, mifepristone, by visiting an authorized clinic or doctor in person. Now, patients can have a consultation with a physician via video or phone or by filling out online forms, and then receive the pills by mail.

But many conservative states have already begun passing laws to restrict medication abortion, including banning it earlier than 10 weeks’ gestation and requiring patients to visit providers in person despite FDA rules. Nineteen states ban the use of telemedicine for abortion. This year, Americans United for Life, an anti-abortion advocacy group, listed laws against medication abortion as first among the organization’s “pressing priorities” for 2022.

“In the last year, Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Montana, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Texas have enacted state-level safeguards to stop mail-order abortion drugs, and the Tennessee Legislature recently sent such protections to Gov. Bill Lee,” said Mallory Carroll, an official with Susan B. Anthony List, an anti-abortion group. “In addition to creating health and safety standards, states are also increasing requirements for reporting complications from abortion drugs. We will be working with allies in additional states to tackle this growing public health threat.”

Residents of states that would quickly ban all abortion methods if Roe were overturned — including Texas, Missouri, Utah and Tennessee — would be legally prohibited from having telemedicine abortion consultations from any location in their state, even if the doctor were located in a state with legal abortion. Such patients would have to travel to a state where an online, video or phone consultation is legal — the IP address of the computer or phone they were using would identify where they were located. Then, they would have to receive the pills by mail at an address in a state with legal abortion, even if it were a post office box or a hotel.

Some patients are already doing this because they live in one of the states that ban the use of telemedicine for abortion. Some aspects of those laws are unclear, including whether patients who take the pills after returning to their home state are violating their state’s law.

If abortion were completely outlawed in those states, many more patients would travel to states where it was legal, reproductive health experts said.

Several organizations, including Abortion on Demand and Hey Jane, now arrange telemedicine or online consultations and mail pills from one of two mail-order pharmacies that are currently authorized by the two mifepristone manufacturers to dispense that medication.

But opponents of abortion and states that outlaw abortion are likely to try to challenge or curtail the ability of patients to cross state lines to get the pills, legal experts said. There may be attempts by states that ban abortion to prosecute doctors and other health providers in states where abortion is legal, for example, or to try to block organizations or funds that provide financial help for patients to travel to other states, Ziegler said.

States that support abortion rights are mobilizing to block such efforts. Legislation in California would provide financial assistance to patients traveling from other states to obtain abortions and increase the number of abortion providers. Connecticut just passed a bill that would prevent abortion providers from being extradited to other states, bar Connecticut authorities from cooperating with abortion investigations from a patient’s home state and allow Connecticut residents who are sued under another state’s abortion provision to countersue.

Medication abortion became legal in the United States in 2000, when mifepristone was approved by the FDA. The agency imposed tight restrictions on the drug, many of which remain in place. But access to the method increased in 2016, when the FDA expanded the time frame within which the drug could be taken — from seven weeks to 10 weeks into a pregnancy.

As conservative states began passing more laws restricting access to surgical abortions, more patients opted for pills, especially because they can be taken in the privacy of one’s home.

The COVID-19 pandemic fueled that trend. The Guttmacher Institute, a research organization that supports abortion rights, reported that in 2020, medication abortion accounted for 54% of all abortions.

Early in the pandemic, medical groups filed a lawsuit asking the FDA to lift its requirement that mifepristone, which blocks a hormone crucial to the continuation of a pregnancy, be dispensed to patients in person at a clinic or doctor’s office. Citing years of data showing that medication abortion is safe, the medical groups said that patients faced a greater risk of being infected with the coronavirus if they had to visit clinics to obtain mifepristone.

For portions of the pandemic, the FDA temporarily lifted the in-person requirement, then permanently removed it in December. In addition, the agency said pharmacies could begin dispensing mifepristone if they met certain qualifications. The agency is in the process of hammering out those qualifications with the two manufacturers of the drug, and reproductive health organizations said that some national retail pharmacy chains have expressed interest in being able to dispense the medication in some states, at least by mail.

The second medication, misoprostol, which causes contractions similar to those of a miscarriage and is taken up to 48 hours later, has long been available for a variety of uses with a typical prescription.

A senior Biden administration official said this week that officials are looking for further steps the administration can take to increase access to all types of abortion, including the pill method. The official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss the leaked Supreme Court decision, said President Joe Biden directed his team “at every aspect in every creative way, every aspect of federal law, to try to do all that’s possible” to protect abortion rights.

As part of that effort, Biden’s secretary of health and human services, Xavier Becerra, said in testimony before the Senate on Wednesday that he has established a reproductive health care task force.

But there are tight limits on what the administration can do without action from Congress. The long-standing Hyde Amendment, which prevents taxpayer dollars from being used to terminate pregnancy, bans the use of federal funds to pay for abortion, including through the Medicaid program, except in cases of rape, incest or life endangerment.

Some experts have suggested that the government could direct resources to groups that provide support, including housing and transportation, to patients who cross state lines seeking an abortion. But it is possible that could violate the Hyde Amendment.

Legal and reproductive rights policy experts said that beyond using his bully pulpit, Biden’s options are limited. They said the administration could turn to the courts and make a legal argument that doctors in the United States have a right to prescribe abortion medication from any state.

“Because the FDA has approved abortion pills as safe and effective and set forth a regimen by which they have to be dispensed, states are not allowed to do anything different, because federal law preempts or is supreme over state law,” said David Cohen, an expert in gender and constitutional law at Drexel University’s law school.

But Lawrence Gostin, an expert in health law at Georgetown University, said there would also be a strong counterargument: that regulation of the medical profession is the province of states, which can therefore regulate what pharmacies prescribe.

Reproductive health experts also predict that more patients will be ordering abortion pills from overseas, through websites like Aid Access — an international organization run by a physician that mails pills — a practice the FDA has tried to stop.

Ziegler and others said it is hard for states or the federal government to stop or interdict the mailing of abortion pills because of the practical difficulties of tracking and identifying every such package.

So far, most states that restrict abortion have long adhered to a principle of targeting providers and others who help patients, but not the patients themselves. Ziegler said it is possible that could also change in a post-Roe landscape because, in circumstances where the abortion takes place outside state boundaries, “there may be absolutely no one else in that state to go after but the patient.”

In the Louisiana Legislature this week, a committee advanced a bill that would allow a patient who aborted a pregnancy, as well as anyone who assisted the patient, to be charged with murder. Opponents of the bill said that it was unconstitutional and could have far-reaching consequences, possibly even for practices like in vitro fertilization.

Some abortion rights advocates said the availability of safe and effective abortion pills has eliminated one of the greatest fears in the years before Roe — but has added a new one.

“One of the sharpest distinctions is really between the idea of hemorrhaging and the idea of handcuffs,” said Kristin Ford, a spokeswoman for NARAL Pro-Choice America. “In the pre-Roe world, there was a legitimate concern about people bleeding out in back alleys. That’s not the reality we face. What we’re looking at now is a world of criminalization.”

Pam Belluck and Sheryl Gay [email protected] The New York Times Company

Read all the Latest News here

Comments

0 comment