views

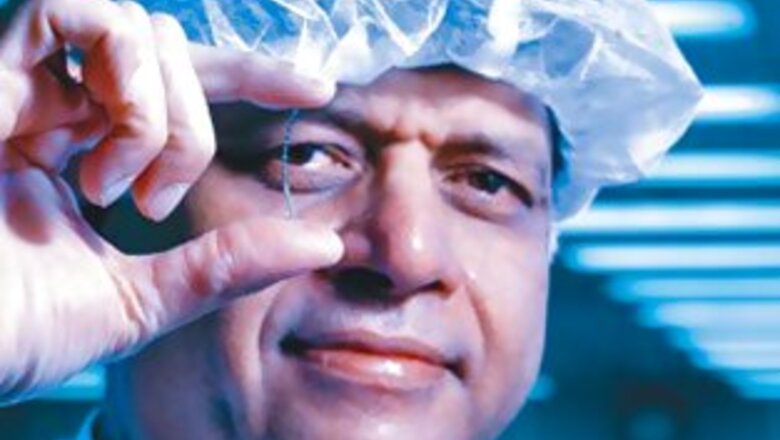

The Man: Vinod Ramnani

Age: 53

Designation: Founder and CMD

Achievement: In the last nine years, he has grown his medical devices company from Rs 19.38 crore to over Rs 800 crore

His Big Bet: Aiming to break into the $6 billion US market for clogged-artery busting stents

Driving through Bangalore’s Electronic City industrial suburb it’s easy to miss Opto Circuits. Hidden behind tall trees, high walls and a closed gate, the company’s nondescript building stands next to glass-and-chrome cousins sporting the best known Indian and international technology brands. But beyond the gates, within Vinod Ramnani’s room, the view changes dramatically.

His company, which went public only in 2000 has now broken into the big, bad $6 billion market for stents, those fine wire-mesh cylinders designed to clear cholesterol-clogged blood vessels. Opto takes on Goliath-like competitors like Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific and Medtronic. With the help of a few shrewd acquisitions, Opto today generates 95 percent of its Rs 800-plus crore revenue outside India. And in a year when most of his peers struggled to maintain their revenue and profits, Ramnani grew both at roughly 75 percent and 60 percent respectively.

Until now, Ramnani has made his living, mostly by selling “non-invasive” medical devices like electronic patient monitors and medical sensors But it is Opto’s “invasive” product line, stuff like stents and balloons that go into patient’s bodies, which holds significant promise.

Opto currently makes slightly over 20 percent of its money selling stents and balloons in Europe and Asia. To break into the big league, Ramnani needs to get them into the US--which at roughly 35-40 percent of the global market is the most lucrative one; and perhaps the most litigious society in the world when it comes to medical products. “Any company that does business in the US has to set aside a part of its profits to meet such eventualities,” says Ramnani. “That is the cost of doing business [there].”

So how did Ramnani get this far? Couple of reasons: The first, perhaps the oldest trick Indians know of--build at a lower cost and sell at a cheaper price than everyone else. Opto makes most of its monitors and sensors from its Indian facilities (Bangalore, Vizag, Chennai and Parwanoo, Himachal Pradesh) where its labour and overhead costs are far lesser than its competitors. And it pays zero taxes due to its Export Oriented Unit (EOU) status.

Consider stents. Ramnani acquired EuroCor, a company with proprietary technology, manufacturing facilities and a distribution network for just €11 million in December 2005 when nobody else saw value in it. That was because the company did not have regulatory approval to market its products. Just six months later EuroCor’s stents got the coveted CE (Communité European) mark, handing Ramnani a regulator-approved stent platform on a platter or a pittance, as you see it.

Due to a combination of these factors Opto can sell its products at an average discount of 10-15 percent in most countries as compared to its larger competitors.

The second reason Ramnani is where he is, is because he made some smart acquisitions. Apart from EuroCor in the invasive medical devices category, Opto acquired Bangalore-based companies Devon and Ormed. In the non-invasive category, which is where Opto started, Ramnani acquired Hindustan Lever’s digital thermometer division, the patient monitoring business at US-based Palco Labs in 2002 and Bangalore-based Altron Industries. In 2008 he acquired US-based maker and distributor of patient monitoring devices, Criticare Systems, for $70 million.

It is tempting, therefore, to think of Opto Circuits as a hopelessly aggressive player. The truth, again, lies somewhere in between. In September last year, Ramnani let go of an opportunity to acquire a European firm for $100 million. The cost, he argues, outweighed the benefits as he could see it.

In spite of walking away from that deal Opto’s debt equity ratio shot up from 0.3 to 1 on account of the debt it took on for the Criticare acquisition. Ramnani wants bring that down to earlier levels by utilising a large part of the Rs 400 crore Opto raised recently by selling equity to a clutch of foreign funds.

PAGE_BREAK

All of this can come undone if the American bet doesn’t work. Sample the odds he is up against.

- America is an extremely competitive market for stents. Manufacturers like Johnson & Johnson have even gone to the extent of advertising their products directly to consumers on television. To grab attention, Ramnani has to spend a disproportionate amount of resources. That holds the potential to neuter the cost-efficiencies achieved until now.

- Much larger competitors have had issues breaking into buyer relationships that have been tied into 2-3 year contracts.

- Opto has applied for US FDA regulatory approval to market its “bare-metal” stents — increasingly out of favour with both doctors and patients in the US who prefer the drug-coated variety. While it is working with the US-based Micell to develop drug-eluting stents, the product is some time away. And the earliest regulatory approvals for even the bare-metal variety aren’t expected until 2010.

- Stent use has been cooling in the US for many years now after high-profile patient studies found stents may offer no better results than medication, in spite of their prohibitive costs (which easily run into thousands of dollars).

Into all of this, factor in the pressure on working-capital arising from a combination of reasons. These include the onus of having to fund increasing levels of inventory in markets like the US, where hospitals pay Opto only three months after a product is used. Add to that a two-month delay that shipping products from India to global markets and then distributing them entails. So Opto’s average receivables cycle extends to 181 days even while it is forced to carry over 100 days worth of inventory.

The effect of the global slowdown cannot be wished away either. Though Ramnani maintains that health care, especially critical-care, is a “recession-proof” business, there will be an overall effect on the sector as hospitals and clinics wait longer before replacing equipment and patients try to delay going in for preventive surgery.

But judging from its journey thus far, Opto is a careful and shrewd player. It is not actively seeking acquisitions for the time being. It has already received approvals for setting up an SEZ in Hassan and another one in Mysore. This is where it will shift its operations, if the tax-breaks incident from the EOU status of its existing manufacturing facilities are aren’t renewed after expiry in 2010.

Its decision to move back manufacturing of Criticare products from Taiwan (where it was being contract-manufactured) to Bangalore has already given it a 20 percent saving in costs. It also has plans to start manufacturing stents in India, an ambitious task no doubt, but one that can help it bring down the cost of each stent below its global counterparts.

Continued investments in R&D — 12 percent of its income in 2009 alone — are beginning to pay off. Its drug-eluting coronary balloon, DIOR, launched in January this year was the first of its kind in the world.

The company says DIOR’s potential market is 40 percent of the overall stent market with 25 percent coming from patients whose existing stents start failing and 15 percent from those who develop infections around an implanted stent.

When Opto Circuits went public in 2000 as a Rs. 20 crore company Ramnani had his back to wall, even promising investors his company would consider software development to “broad base our business”. In 2009, Opto may not have its back to the wall, not yet at least, but is at the cusp of a series of inflection points that will decide its next growth trajectory.

Comments

0 comment