views

Basic Nutrition

Determine how much food your cattle needs depending on their breed. The breed and type of cattle you raise is key when figuring out their feed amounts. It also affects their nutritional requirements, as some breeds need more protein or certain vitamins, for instance. Breed is a bigger determinant of diet than sex, which surprisingly has very little impact. Food Requirements for Different Cattle Breeds Dairy cattle require more feed to maintain their weight than beef cattle. British breeds (Angus, Shorthorn, or Hereford) have lower food needs. Continental breeds (Charolais or Limousin) typically need more energy and protein. Exotic breeds have higher feed requirements than continental or British breeds.

Figure out how much weight your cattle should gain per day. This is known as average daily gain (ADG). It’s determined by your cattle’s current weight, their body fat composition, and their age. Take the target weight of your cow and subtract its current weight. Then divide that number by how many days until you want the cow to reach its target weight. The resulting number is its ADG. For example, younger cattle typically need to gain anywhere from 1.5 to 3 pounds (0.68 to 1.36 kg) per day. ADG can be positive or negative. A negative ADG means the cow needs to lose weight. Smaller or thinner cows will require more food to reach a healthy weight.

Adjust your cattle's food needs based on the environmental conditions. Everything from the length of the grazing season to average temperatures can play a role in how much and what you feed your cows. Think about factors like the condition of the pasture, how cold it gets at night, and what crops grow in your region. The type of operation you run is another environmental factor. Cattle raised in a pasture tend to be pickier eaters than those raised in a dry-lot. How to Feed Cattle Based on Weather and Location Increase food if...The temperature drops below −4 °F (−20 °C).There are high winds in the area.The pasture is very muddy so food is hard to find. Decrease food if...The temperature goes above 86 °F (30 °C).Night cooling does not occur.

Choose a high-quality feed that meets the nutritional requirements. There are a variety of options when it comes to cattle feed. Pick yours based on what nutrients your cows need and what’s available in your area. Then, send it to a local feed lab where they’ll test it to ensure it’s the best quality. Common Types of Cattle Feed Hay Grain (oats, wheat, barley, rye) Straw or chaff By-product (soybean meal or alfalfa pellets, for example) Vitamin or mineral supplements Salt Milk Fats and oils

Increase the amount of food for pregnant or nursing heifers. These cows need more nutrients, vitamins and minerals, and water to either grow their babies or produce milk. Their nutritional requirements are highest during the last 3 months of the pregnancy and just after they give birth. How much food a nursing cow needs starts decreasing 3 months after calving. Keep track of each cow’s reproductive phase in a journal or spreadsheet so you know when to increase or decrease their nutrition.

Work with a veterinarian to pick the ideal rations for your cattle. Because feed rationing is so complex, it's best to get professional advice and analysis from a veterinarian or cattle specialist. They'll help guide you on how much to give your cows, along with what the nutritional makeup of the food should be. Cattle feed contains a food label on the packaging that lists the ingredients and breakdown of vitamins and minerals. What to Consider When Choosing Feed Rations Know how much dry matter intake (DMI) your cattle eats on average each day. Analyze the energy, fiber, and protein contents of the feed. Look for a calcium-to-phosphorous ratio of 2:1. Check that the vitamin and mineral levels are high enough for your cattle's needs.

Special Dietary Needs

Consider the productivity status of your cattle. Cattle are divided into 5 different classes, based on 3 general types of intended production: lactation, breeding, or meat. These types dictate a variety of factors, such as if and when the cattle needs to gain weight. Differentiate your cows based on these types and specific conditions: Lactating cows—Consider how long they have been producing milk, how many times they have produced milk in their life, how much milk it makes, its pregnancy status, and the expected birth weight of its offspring. Dry (non-lactating) cows—Think about whether she is bred or not and how many months she is pregnant. Bred heifers—Consider whether she is bred or not and how many months she is pregnant. Feeders and Replacements—Feeding cattle for slaughter comprises of 2 groups of cattle: those that are "backgrounded" and those that are "finished." It's important to consider the targeted slaughter weight (or mature weight for replacement heifers and bulls), and targeted grade, marbling, and yield at slaughter. Herd bulls—All information already mentioned is needed, minus that for lactation, pregnancy, and carcass evaluation.

Consider the breed and type of cattle you are raising. Breeding plays a significant role in determining feed rations. For instance, dairy cattle have higher maintenance requirements than beef cattle, and so need to be considered differently. The kind of formulation used for lactating dairy cows in a dairy milking system is more complex than one for beef cattle, thus the formulation for dairy cows is usually separate from that intended for beef cattle. Dairy cattle breeds include Holstein, Jersey, and Brown Swiss, to name a few. In a feed formulation, Simmentals and Fleckviehs are also included with dairy. Beef cattle breeds (aside from Simmentals and Fleckviehs) are generally lumped into 3 categories: British-type, Continental, and Exotics. British breeds include Angus, Shorthorn, and Hereford. Typically, these are your average range cattle, or those cattle that have lower maintenance requirements and thus are considered better converters of feed into milk or muscle. Continental breeds, such as Charolais and Limousin, may require more supplementation in energy and protein when on a roughage or grass-only diet. But, if hay and grass quality is poor, then both will need more the supplementation to thrive. Exotics include the Brahman-type cattle like Santa Gertrudis, Nellore, and Sahiwal, and composites like Brangus and Braford cattle. The first group is linked separate because they need a little higher maintenance requirements than either the non-Simmental Continental group and the British-type group.

Assess the state of your cattle's coat. In terms of assessing your animals themselves, hair depth, hair condition, and hide thickness are factors that impact how you feed them, especially going from summer into winter and vice versa. No matter how sudden or gradual changes in the coat are, if there are problems with the coat they should be accounted for when determining how and what to feed your animals. Hair depth—Length of the first layer of hair (the finer, softer hair close to the skin) should be more pronounced in the fall and winter than spring and summer when it is shed out and a light hair coat is worn. This is to allow the animal more external insulation against the cold. Depth isn't needed numerically, just whether it's in a "summer" or "winter" condition. Hair condition—This just asks if the hair coat is wet, muddy, or snow-covered. All of these conditions can compromise the insulating qualities of the hair coat, and thus the threshold temperature of the animal and that animal's maintenance requirements. Hide thickness—The thicker the hide, the greater the external insulative qualities, and vice versa for thinner skin in cattle. Herefords and Devons are known for having thick hides. Other beef breeds, from Angus to Shorthorn and Charolais to Gelbvieh are considered average. Dairy breeds and Zebu/Brahman cattle have thinner hides, but what's interesting is that Holstein-Friesians have much thicker hides than Jerseys.

Don't take sex into consideration. From a nutritional aspect, sex plays a very minor role in the differences of nutritional requirements. Studies have shown that nutritional requirements between heifers and steers or heifers and bulls (or cows and bulls) are not statistically different. Differences in sex only affect growth rates to a minor extent and how nutrients are allocated to bodily tissues: either as muscle or fat. For example, if growth rate between a group of steers and heifers was the same, and they were fed the same ration, the heifers would be likely to lay down more fat than steers will. The only concern with sex is the actual diet formulating in regard to reproduction, especially when it comes to cows. Females, especially mature cows, are probably the most difficult to formulate for because they have different requirements that are associated with where they are in their reproductive cycle (i.e., how many months into pregnancy they are, or how far along in their lactation cycle they are).

Weight and Body Condition

Determine the weight of your cattle. Probably the most important thing to know when determining the right feed for your cattle is how much each animal weighs. If you know how much each individual weighs, then you can create a diet that can either keep them at their weight or make changes to their diet that will impact their size. It makes no difference if the weight is in pounds or kilograms.

Body condition score (BCS) your cattle. Body condition scoring is judging the level of fat the animal is carrying. Condition scoring is done by looking and feeling the latter half of the animal, from the ribs to the pelvic region. Then you use a chart to assess the animal's number score in relation to its physical condition. The lower the score, the thinner the animal. In the Canadian system, the score goes only up to 5 (1 to 5 scoring). In the American System, it goes from 1 to 9. You will need to compensate and adjust what you're feeding lower scoring animals in your herd so that those animals can gain weight. Thinner animals tend to have higher requirements for nutrients than those that have a moderate score or higher. This can translate into higher consumption levels. This also means that you need to invest more in higher-quality feed to bring those animals up to a desired body condition by a certain amount of time (calving, breeding, or even as meat cattle for sale). It's different with fatter or moderate-framed cattle. With these, you have to manage feed so that they're either maintaining their weight, or losing some of it. It's actually easier to make a cow lose weight than for her to gain it, economically and metabolically speaking, which will be explained in more detail in the section on ration creation below.

Take the pecking order into consideration. Body condition score is an especially good indicator of where particular individual cattle may be in the pecking order. Thinner cows may be the hard-keeper cows that need more energy and protein than the rest of the herd, but they may actually be those that are being bossed around too much and can't get the nutrients that they need for themselves. The fatter cows, too, may either the bossy cows or the easy keepers or both. Cattle on the lower end of the pecking order tend to be less competitive for food than those that are considered the "boss" animals. The bigger bulls, bigger/stronger cows, more robust animals, etc. The "bossy" or "bully" cattle tend to come in when the weaker ones try to get at the feeder first to get what they can, and push those weaker cattle out so they can eat what they like until they are full. The lower-pecking-order cattle don't get what the need themselves, so become thinner than the bossier cattle. Separating the two groups into different pens can help remediate this. Or, spreading feeding stations around may also help because it gives those lower down in the pecking order a chance to get what they need with lowered competition from the bovine bossies in the herd.

Determine the desired average daily gain (ADG) you would like to see. Average daily gain is how much weight an animal, no matter the class or type, is expected to gain or even lose during the feeding period. Target ADG is really important with growing cattle, regardless of whether they are meant for the meat market or for the breeding herd. Young cattle should be growing and gaining at least 1.5 to 3 pounds per day. ADG of 3 pounds per day is pretty high, and optimum for feedlot cattle, but probably not so practical for either feeders and replacement heifers and bulls. Thinking about average daily gain is actually a good way to determine feed efficiency, residual feed intake, foraging ability, etc. of your cattle. Those animals that can maintain their weight on feed that may typically cause a dairy cow to quickly lose condition, would be considered as having good feed efficiency. On the other hand, those that need a little extra "boost" with some grain or extra pellets are those that need to be watched for potential weight loss. One of the primary reasons for taking ADG into consideration is to avoid too much fat deposition in and around the reproductive tracts of cattle, which will impair fertility, milking ability, and calving ease, the latter 2 being crucial for heifers.

Reproductive Needs

Keep track of the reproductive phase of all of your cattle. This is not nearly so important in bulls and steers as it is in cows and heifers. However, bulls have nutritional requirements that surround and affect their breeding ability and fertility. With females though, both timing in the gestation and lactation period will determine where cows and heifers are in nutritional requirements. Gestation and Lactation—The average length of gestation is 285 days, or about 9.5 months, three stages of pregnancy are apparent: first, second, and third trimester. Also, a cow is most likely also lactating during her pregnancy. Dairy cows lactate for a full 10 months, beef cows may be lactating (suckling a calf) for 6, 8 or even 10 months after calving. Females are usually bred back 2 to 3 months after they have calved. Because these dates and times coincide so closely together, nutrient requirements are mainly affected by whether the cow is in fact lactating, versus in pregnancy. Replacement and Bred Heifers—Heifers need a little more attention because they are still growing, replacing their baby-calf teeth, and also are feeling the strain with becoming new mothers for the first time (or new to the milking dairy herd). Their nutritional requirements with regards to gestation and lactation are no different from the mature cows. However, energy supplied must be limited so that they are not putting on too much fat, which will compromise milking ability and calving ease later in life. Cull Cows or Heifers—Feeding requirements for cull females are no different than if they were a part of the breeding herd. They may be destined for slaughter, but nutrition shouldn't be compromised just because they're suddenly culls. Herd Bulls—Fertility of the bull is of most importance when considering nutrition and feeding. Since you will likely have few bulls, fertility of bulls is much more imperative than for cows. Body condition of the bull plays a large part, because they can't be overly thin or too fat or they will lack the energy to service every opportune estrogen-hyped cow in a short period of time. Bulls often come out of the breeding season thinner than when they went in, so the time they have to rest up is the best opportunity to feed them up so that they gain back what they lost.

Increase nutrition in cattle that are at the end of a pregnancy. Nutritional requirements associated with pregnancy do not begin to increase until a cow is in her last trimester (last three months of pregnancy). Her nutritional requirements continue to climb after she has given birth. Requirements of the heavy-pregnant cow increase because the fetus in her is growing and needing more energy and protein to grow. Careful consideration needs to be made with either essential, and often limiting, nutrients because of the fear of cows having problems giving birth (dystocia). However, note that there is some data correlating with how genetics for calf size at birth (in terms of birth weight) is more determined by the genetics of the bull, very little by the dam. Once a cow has given birth, she begins to suckle a calf (beef cows), or lactate to be put as part of the milking cow herd (dairy cows). Both types of cows will experience a climb of nutritional requirements until they reach 2 months after calving, and some won't reach the peak until 3 months after calving.

Increase key nutrients for pregnant and nursing cows. Nutritional requirements emphasize need for more energy, protein, calcium, phosphorus, and other vitamins and minerals. And since a lactating cow is producing milk for either her calf or for all those cow-milk-hungry humans out there, she also needs more water.

Decrease feed as milk production decreases. After she has passed the 2- or 3-month lactation and re-breed mark, nutritive requirements decrease along with milk production. By the time the beef cow weans her calf at usually 6 or 8 months post-calving (she should be into her second trimester by then), her nutrient requirements dip significantly until she begins her third trimester again. Dairy cows' nutritional requirements decrease less dramatically because they are not "dried off" (milk production is slowed to nothing by stopping regular twice-per-day milking) until they have reached 10 months post-calving and are a third of the way into their last trimester. All of these timings of gestation and lactation are why it is important to keep records on your animals. The better records you keep on calving, breeding, lactating, and weaning (the latter especially for beef herds), the more accurate you can get with keeping on top of a healthy ration for your cows and heifers.

Environmental Concerns

Consider the type of operation you run. The feeding requirements of cattle raised in a dry-lot or "feedlot" environment need to be viewed differently than cattle on pasture. Cattle in a dry-lot have their feed harvested, stored, and brought to them compared with cattle on pasture who have to find it themselves. Pastured cattle may actually be more picky about what they eat (depending on pasture system set up), than the choice they have with the bale of hay. Cattle in a dry-lot also have mud to contend with, and if straw or sawdust is not offered as bedding, this will affect their consumption and requirement levels. Pastured cattle usually do not have this problem, and if they do, it's only briefly when they need to get a drink of water. As far as consumption levels and nutrient requirements, the difference between feeding cattle in a drylot versus grazing them on pasture is minimal to insignificant.

Assess what you can feed your cattle. Your location plays a very big role in feed availability, as well as the environmental conditions your cattle may experience. These conditions will affect how much they eat and what their nutritional needs are. The types of winters and summers you get, length of grazing season (which translates into length of feeding period), average ambient temperature, and other environmental factors should influence what you can feed your cattle and how much they're even expected to eat. There are crops that are more available to some producers than others depending on their location. Lespedeza, for example, is a forage introduced from Central Asia that is adapted to grow from Missouri and parts of the more moist Great Plains east to much of New England and south to Florida and Texas. You won't find this forage growing further west in Montana or north in Alberta or British Columbia. This primarily because of moisture limitations and freezing winters. Alfalfa, on the other hand, is found all over North America. Corn can be grown as a feed in much of the United States and now even the southern and a few central reaches of Canada (especially Ontario, and into the Prairie Provinces) because of the ideal heat units available for it to get 8 to 12 feet tall. Where it can't be harvested as grain, it can be used for winter grazing cattle, or harvested as silage.

Take environmental factors into consideration. The climate you live in and the seasons you experience, no matter how short, long, or pronounced they are, have a real impact on the feeding of your animals. Environmental stressors are what you are going to be most concerned with because they will affect how and what you need to feed your animals. Consider the following factors: Current temperatures—Nutritional requirements, and how much cattle eat, can be greater or less than average if the temperature is at -20ºC or 30ºC. Generally speaking, a moderate-conditioned cow is expected to have a 1 percent increase in maintenance energy requirements for every degree lower than 20ºC. If, for instance, a thin cow is trying to keep warm at -20ºC, it will eat more and need more energy. Previous month's temperature—It takes time for a cow to acclimatize to a new or different temperature it is experiencing. Night cooling—This is only accounted for in hot summers. If night cooling is a factor, then intake is reduced by only around 10 percent. If not, intake is reduced a lot more (around 35 percent) because cattle are almost unable to dissipate heat accumulated during the day. Wind speed (average)—The higher the wind speed, the more the insulating capabilities of the hair coat and body condition are going to be compromised, especially in cooler seasons like autumn and winter. In fact, wind can have a greater affect on weight gain and animal performance than ambient temperatures alone. Mud—A muddy lot can decrease dry matter intake levels by 15 to 30%. The extent and duration of the mud can make determining dry matter intake difficult. Heat stress—Heat stressed animals have an increase in maintenance energy requirements because they are trying to dissipate excess heat built up from ambient temperatures greater than 30ºC. A 7% to 18% increase in maintenance requirements is expressed when the animal is showing rapid, shallow breathing, and when the animal is open-mouthed panting. Remember, prolonged heat stress can be lethal. Over-conditioned, lactating, and dark-haired cattle are more susceptible to heat stress than any others.

Feed Type and Quality

Determine what feeds are available. You will likely have a wide variety of different types of feeds to choose from for your animals. These can vary from different types of hay to by-products to grain. The main feed types and their ingredients include, but are not limited to: Mix—A combination of hay, silage, grain, supplement, mineral, salt, by-product, salt, vitamin, etc. Hay—A grass, legume, or grass-legume mix. Pasture available for grazing may be also included in this feed type, even though pasture isn't sun-cured harvested forage like hay is. Grain—Includes corn, oats, barley, wheat, rye, and triticale. Silage—Includes corn (referred to as ensilage), barley, winter wheat, rye, winter rye, triticale, oats, and pasture grass. Straw—Typically includes cereal grain chaff baled, barley, oats, triticale, rye, and wheat. Legume or pulse straw also includes pea, flax, lentil, and greenfeed. Chaff—Similar to straw. By-Product—Can be distillers grains (wheat or corn, wet, dry, solubles), wheat middlings, brewers yeast, bakery product, corn gluten, cottonseed meal, soybean meal, alfalfa pellets or cubes, barley malt sprouts, beet pulp, canola meal, canola cake, and oat hulls. Supplement—Is usually in the form of protein as a percentage with a mix of other minerals and grains. It also includes non-protein nitrogen (urea) that can be used for cattle older than 6 months old. Salt—Comes in block or loose form. Most blocks are 95 to 98% salt and 5% or 2% mineral respectively. Vitamins—Vitamins A, D, and E are sold in various forms as a feed-mix supplement. Minerals—Are calcium [Ca], phosphorus [P], sodium [Na], chloride [Cl], potassium [K], magnesium [Mg], and sulphur [S]. Microminerals are cobalt [Co], iodine [I], iron [Fe], molybdenum [Mo], manganese [Mn], copper [Cu], zinc [Zn], and selenium [Se]. Mineral bags with Ca and P are usually sold as a ratio of 1:1 or 2:1. Less common are mineral sold as greater than 2:1, though 7:1 is still appropriate for cattle. Macrominerals are labelled as a percentage while microminerals are labelled as mg/kg or parts per million [ppm]. Milk—Used for calves only and comes as cow's milk or milk replacement formula in powder form. Fats—Includes tallow, sunflower oil, and canola oil.

Obtain the feed you need. Various feeds can be obtained from other producers, the local feed store, or that are made yourself. In many cases, you will use a combination of buying and making your feed, depending on the specific ingredients you want to feed your cattle. If you are considering making your own feed, determine whether you have sufficient money, land, equipment, labor, and time to do so.

Assess your feed by smelling it and looking at it. Sight and smell are much less accurate means of judging quality feed that scientific testing. However, you can use them to judge whether feed is generally acceptable. For instance, smelling and looking at the feed determines how dusty, moldy, or even smelly the feed is. Hay and straw that are a little dustier and smell or look moldy may be lower quality, however if this is only appearing on the outside, the inside may be better quality. Mold and dust are unavoidable, especially if bales are stored outdoors, or forage is baled up wetter than it should be. Moldy hay will have to be fed to cattle, but it can reduce palatability or reduce feed intake to the point that cattle may refuse the feed altogether. Certain fungal molds can produce mycotoxins, which can cause health problems like infertility and abortions in breeding females. Since not all molds produce mycotoxins, the ones that do produce amounts that can be unpredictable. Silage that has a putrid smell to it is obviously feed that is getting spoiled. Not only will it smell like rotten bananas, but it will has have a dark, slimy look to it instead (and feels slimy when handled). Like with moldy hay, this can reduce palatability. Good silage has a brownish color that gives a sweet, fermented smell and, if tasted, the grains have a tangy, sharp, almost sweet taste. Grains with mold can be cause for concern too. They'll have the same musty, moldy smell like hay, and may have potential for the same problems. Hay, especially, that looks green is usually an indicator of good quality. But, green hay can still be had when it's tested to be as good quality forage as straw. Higher than normal precipitation with high temperatures, cutting mature forages, poor soil fertility, and improper curing and/or storing of bales can impact hay quality, even though the hay may look green and is not that stemmy. Usually stemmy hay or hay with a lot of stems is deemed poorer quality hay than that with more leafy material. The reason is that stems are often less palatable and retain less energy and protein than leaves do. But, if hay is harvested during a time of a lot of moisture and a lot of heat, even hay with less stemmy material is going to be poorer quality than you'd think.

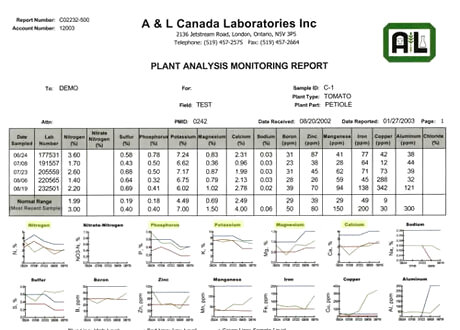

Have your feed tested. The best time to test your feed is right before it is fed to your animals. Forage samplers, probes, or corers, which are long hollow tubes designed to "core" into a bale of hay, straw, etc. Then send your sample to be analyzed at your local feed lab. Do not test your feed right after it has been harvested, although there's nothing wrong with sticking in a probe in a hay bale to test for moisture, as is often done (or should be) when making hay. Bale corers have widths that vary from 1/2 or 3/8" to over 1" or 1-1/8". Typically the larger diameter ones work best especially if you have hay or straw that is more stemmy. Where these large corers will cut through the stems, the smaller diameter samplers might slip past them and give misleading results when the samples are sent in. Take at least 10 to 20 samples per "forage lot," or the silage or hay that came from one field. That means taking a sample from at least 10 or 20 bales that came from that same field to get a representative sample. For silage, that means at least 10 or 20 samples from the same pile. Core each bale 12 to 15 inches in. The cores should be taken from the string- or netting-side of the bale, not the flat side, and pushed straight in (parallel to the ground), not at an angle. For silage, samples taken from 3 to 5 feet in. Options are to bag each sample, or to collect a set of samples from one lot in a clean, dry 5-gallon pail so they can be mixed and stored in plastic bags. Squeeze all the air out when you put the sampled forage in the bag, and send it to your local feed lab.

Use feed analysis results to determine how good (or poor) quality the feed is. Energy content and protein are especially important to pay attention to when considering which diet or what feed will contribute to weight loss or weight gain, meet requirements for lactating cows or growing calves, or be at maintenance requirements. Ideally, energy and protein should be at the optimum requirements, never too much nor too little. Pay attention to NDF (neutral detergent fibre), ADF (acid detergent fibre), TDN (total digestible nutrients), and DE (digestible energy) values for energy (carbohydrate/sugar) and fibre content, CP (crude protein) for protein content, CF (crude fat) or Ether extract (fat) for fat content, and Ca (calcium), P (phosphorus), K (potassium), S (sulphur), Mg (Magnesium), Na (Sodium), and Salt (NaCl) for macrominerals, and Fe (Iron), I (Iodine), Co (Cobalt), Cu (Copper), Mn (Manganese), Mo (Molybdenum), and Zn (Zinc) for microminerals. If you're seeing tests that of a feed that exceeds or falls short of requirements, consideration will be needed to limit the amount fed and/or include another feed to offset the amounts. Macrominerals, also called "major minerals, are minerals that are needed in large quantities or concentrations in the diet, usually on a per-gram (or per-ounce) basis. Microminerals, also called trace minerals, are needed in smaller concentrations, often as parts per million (ppm), milligrams (mg) or nanograms (µg).

Rationing

Understand the complexity of feed rationing. Creating a feed ration is a very complex process. A rough estimate on how much feed to give your cattle can be done by hand, but you are better off working with a dairy or beef nutritionist or veterinarian. It's also good to have a feed formulation software program available to you so you know exactly what to feed, how much to feed, and how it will impact your cow herd. Please contact your local extension beef specialist or veterinarian if you need help formulating your feed rations. A ruminant nutritionist (beef or dairy) can help you determine whether you are doing the right thing or see improvements that need to be made to your feeding operation.

Utilize feed tables to get a general idea of the nutrient content. Various beef and dairy publications through magazines, agricultural extension services via universities, colleges, and government agricultural ministries, and books on ruminant nutrition, will or should have feed tables available to look at. Generally, these tables will give you a good idea of what feeds to consider as supplementation or alternatives for your animals. These are only general nutrient content values for many feeds that are listed. For specific nutrient content of the feed that you have on hand, look at the contents on the feed bag and/or send in a sample to a feed lab to have it tested.

Calculate the ideal average dry matter intake (DMI) for your cattle. Average daily intake on a dry matter (DM) basis is a way to figure how much forage a cow will eat per day when that forage has all the water taken out of it. Dry matter weights are taken when a feed is sent to a lab and "cooked" or roasted until it's nothing more than crispy plant material. DMI is a way to take out the variation of moisture content of the feed so that how much a cow, bull, steer, heifer, or calf will eat can be calculated based on the quality of the feed and the animal's nutrient/energy requirements. Numerically, the amount a bovine will eat is on a percent body weight basis. The average rate of consumption is subjective. Many publications state "average" percent body weight consumption as between 2.0 and 2.5 percent of body weight. But many agree that the lowest percent body weight an animal should consume is 1.0 percent (straw and low-quality feeds), and the highest at 3.0 percent (excellent quality forage).. In order to calculate the estimate of a bovine's average daily dry matter intake, use the following formula: Body weight (in pounds [lb] or kilograms [kg]) x 0.025 = Daily Dry Matter Intake. For example: 1500 lb cow x 0.025 = 37.5 lb DM forage per day. To calculate how much a cow will consume on an as-fed basis, find out first what the moisture content of a feed is. For example, grass-hay is typically at 18% moisture. To get the dry matter content, subtract by 100: 100 – 18 = 82% DM. So, to find out how much a 1500 lb cow will eat on an as-fed basis per day, calculate it out this way: 1500 lb x 0.025 = 37.5 lb DMI; 37.5 lb DMI / 0.82 DM = 45.7 lb hay as-fed.

Determine the energy content of the diet. Energy content is expressed in terms of TDN (total digestible nutrients) or DE (digestible energy). ADG for growing and finishing cattle is determined by energy content of the diet. ADG is less important for mature cows and bulls, though when needing to understand how much energy in the diet is needed for dry, pregnant cows in the middle of winter versus lactating females in summer is certainly important. Energy needs can be exceeded (to a certain extent, and as long as fiber needs are also met) for all classes of cattle in order for them to meet their maintenance and productivity requirements. Maintenance energy needs should be exceeded if a cow is too thin, but energy has to be cut back if that cow is over her desired body condition score. The rule of thumb of energy requirements for breeding beef cows, in order to maintain their body condition score through winter, is 55-60-65: 55% TDN for mid-pregnancy, 60% TDN for late-pregnancy, and 65% TDN for after calving. Energy requirements for dairy cows is different because TDN isn't used to determine energy requirements so much as net energy (NE) is. Replacement heifers and stocker cattle should be fed a ration where energy is around 65 to 70% TDN so that they can achieve a rate of gain at around 1 to 2 lbs per day or higher. At minimum, for growing cattle TDN value should be no lower than 55% for maintenance and some growth. Any lower would mean loss in body condition, and possibly stunted growth. But on the flip side, diets that exceed 80% TDN can lead to problems like acidosis if there is not enough fiber to counter the effects of acidosis.

Look at the fiber content of the feed. Cattle are ruminants and cannot subsist without sufficient fiber in the diet. If fiber was minimal (less than 15 to 20% of the total dry matter ration), damage to the rumen wall would result, as well as other problems like acidosis. Optimum fiber for cattle all cattle should be at 40 to 50%. Lower quality feeds see fiber levels climbing up to 65% of DM ration or higher, potentially causing impaction and reduction in nutrient uptake. There are no rules of thumb for fiber content of different rations for different classes of cattle. Fiber in feed tests is expressed as neutral detergent fibre (NDF), or acid detergent fibre (ADF). NDF refers to fiber that is insoluble in neutral detergent and includes cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. It includes all plant cell wall material that is only partly digestible. Typically as NDF increases, DMI (dry matter intake) decreases. ADF refers to fiber (largely cellulose and lignin) that is insoluble in acid detergent. It is comprised of the highly indigestible portions of plant material, generally the lignified material. As ADF increases, digestibility of feeds decrease. Effective NDF (eNDF) is the amount of NDF that stimulates chewing and rumen motility. Long-stemmed forages stimulate more chewing and ruminating, which stimulates more salivation. As salivation increases, so does buffering capacity of the rumen. Buffering pH in the rumen is important for dairy diets and finishing rations because it helps reduce rumen pH levels from dipping below what's acceptable (i.e., pH 6 or higher). The higher the end of a feed, the greater the buffering capacity of the rumen.

Evaluate and determine protein requirements of your cattle. This should correlate to protein content of the feeds. Typically, younger and lighter-weight cattle have higher protein requirements than older, heavier cattle. Lactating cows also require more protein than dry cows and dairy cows need more protein than beef cows regardless of whether both are lactating or dry. Protein content in feeds and for livestock are denoted as crude protein (CP). Crude protein content should be on an dry matter basis when looking at feed labels or feed tests. Some feed tests also give CP in as-fed, but the more accurate measurement of protein content in the feed is by dry matter. A rule of thumb for feeder/stocker beef cattle is the 14-12-10 rule: 14% CP for weaned calves 550 to 800 lbs, 12% CP for calves 800 to 1,050 lbs, and 10% CP for feeder cattle 1,050 lbs to finish (1350 to 1400 lbs). A rule of thumb for an average pregnant to lactating/suckling beef cow (British-Continental-mix cattle excluding Simmentals) is the 7-9-11 rule: 7 percent CP for mid-pregnancy cows, 9 percent CP for late-pregnancy cows, and 11 percent for post-calving nursing cows. For instance, A 500 lb weaned steer with an ADG of 2 pounds per day requires 12.8 percent CP. If he has an ADG of only 0.5 pound per day, he will need 8.5 percent CP. Similarly, if a 300 lb steer where to have an ADG of 3 lb/day, he would require about 22 percent CP. Lower protein available (or lower requirements) begets a lower ADG. Another example could be: A 1100 lb cow with a low milking ability of only 10 lb of milk/day and 2 months post-calving requires 8.9% CP to maintain her body condition. However, if this same cow had a superior milking ability of 30 lb of milk per day, also calved 2 months ago and is having her body condition maintained, she will need around 12.5% CP.

Check what your calcium-to-phosphorus ratios are in the available feeds. An optimum Ca:P ratio should be 2:1, though ratios that are up to 7:1 aren't going to hurt cattle either. However, if phosphorus is in excess of calcium problems could occur from abnormally loose stools to inability to absorb calcium, since too much P can interfere with the body's ability to take in and utilize Ca for cellular and bodily functions. Calcium is really important for lactating cows and heifers. Limiting Ca can cause reduced milk production, but limiting Ca so the cow is forced to utilize calcium from her body rather than depending on the feed she's given before calving will also reduce incidence of milk fever, especially in dairy cattle. But, it can be a double-edged sword because milk fever is also caused by a sudden drop of calcium in the blood after calving, so calcium levels need to be watched closely in nursing or milking cattle. Calcium is a macro-mineral, so the NRC (Nutrition Research Council) suggests that a maximum level of 2% of a DM (dry matter) ration needs to be fed to cattle. However, dietary calcium levels in feeds vary as well as calcium needs in different classes of cattle. Not all cattle need the same amounts of calcium as the other. Calcium is readily accessible in legumes like alfalfa, and oilseed meals are also good sources. Supplemental sources include calcium carbonate, ground limestone, and dicalcium phosphate. Phosphorus is important for all classes of livestock, but nutrient requirements vary according to age, weight, and type and level of production. Deficiencies in phosphorus can cause a condition called pica which results in abnormal behaviours in normally herbivorous animals like cattle, which is a more severe condition coming out of depraved appetite. Cattle experiencing pica will chew wood, soil, and bones, and some serious pica cases have reported cattle eating other animals like chickens or chewing on carcasses, just so they can quench their craving for minerals like phosphorus. Pica also comes from a lack of salt, cobalt, and iodine in the diet. The NRC suggests that the maximum phosphorus level would be 1% of DM ration. Oilseed meals, grain, grain-by products and other high-protein supplements are typically high in P.

Analyze the mineral content available. In addition to the Ca:P ratio, other minerals like potassium (K) and magnesium are important to look at. Minerals like Selenium, Sulphur, Cobalt, Iodine, and Sodium need to be looked at so they don't go into toxic levels nor are deficient in the diet. This is where supplementation may be necessary with loose mineral and salt blocks or loose mineral-salt mixes. Mineral requirements are as follows: Magnesium (Mg) requirements—Growing and finishing cattle, 0.10% of DM ration; Gestating (pregnant) cows, 0.12% of dry matter ration; Lactating cows, 0.20% of DM ration. Potassium (K) requirements—0.6% of total DM ration. Maximum level is 3% of total DM ration. Sulphur (S) requirements—0.15% of DM ration. Maximum must be at 0.4% of DM ration. Cobalt (Co) requirements—0.10 ppm of DM ration. Maximum tolerable level is 10 ppm, or 300 times the recommended amount. Copper (Cu) requirements—10 ppm of DM ration. Maximum tolerable level is 100 ppm. Iodine (I) requirements—0.5 ppm of DM ration, or 1 mg/day for a 1100 lb (500 kg) cow. 50 ppm is maximum tolerable level for calves. Iron (Fe) requirements—50 ppm of ration DM. 1,000 ppm maximum tolerable for cattle. Manganese (Mn) requirements—40 ppm of DM ration for mature cows and bulls, and 20 ppm of DM ration for growing finishing cattle. Maximum tolerable level is 1000 ppm. Molybdenum (Mo) requirements—Not established. Copper and sulphate alter molybdenum metabolism, thus arriving at Mo requirements is impossible. However, maximum tolerable level is 5 ppm. Selenium (Se) requirements—0.10 ppm of DM ration, however the NRC suggests that 2 ppm of DM ration is maximum for all classes. Zinc (Zn) requirements—30 ppm of DM ration. High-milking beef cows have higher requirements, with milk containing 300 to 500 ppm of Zn. Maximum tolerable level is 500 ppm.

Check for vitamin levels in feed. Cattle outdoors on fresh forages typically do not need vitamin supplements unless there are conditions that will cause deficiency symptoms, such as a deficiency in a mineral that is closely linked with a particular vitamin, like Selenium to Vitamin E, or Cobalt to B vitamins. Certain conditions or feeds can limit vitamin availability to livestock, but typically healthy cattle that aren't grazed don't need to be supplemented regularly with nutrients like B vitamins or vitamin C, D, or K. Vitamins E and A are needed if feeds are sourced from soils that are deficient in selenium, and feeds are low quality with poor carotenoids, respectively. Vitamin requirements are as follows: Vitamin A requirements—Variable according to class, age, and weight of cattle. On a dry ration basis, the vitamin A requirements are about as follows: Growing finishing steers and heifers—1,000 IU/lb (2,200 IU/kg of boy weight), pregnant heifers and cows—1270 IU/lb (2,800 IU/kg of body weight), lactating cows and breeding bulls—1,770 IU/lb (3,900 IU/kg of body weight. Vitamin D requirements—125 IU/lb (275 IU/kg of body weight) of DM ration. Vitamin E requirements—dI-alpha-tocopherol acetate added to dry ration at level of 15 to 60 IU/kg of body weight of dry matter intake (DMI; or 0.31 to 1.25 IU/kg of body weight) in non-stressed beef cattle. Supplementation may be needed with selenium-deficient soils. Growing calves need higher vitamin E requirements when newly weaned and just received at a new farm because they are undergoing a lot of stressed. They should get 400 to 500 IU/day (1.6 to 2.0 IU/kg of body weight). This can be decreased down to around 300 IU/day (1.25 IU/kg of body weight). Once cattle are adapted to new conditions feedlot cattle should go back into recommendations of 25 to 35 IU/kg DMI or 0.52 to 0.73 IU/kg of body weight. Vitamin K requirements—None recommended. Abundant in pasture and green roughage, but deficiency symptoms come about when feeding moldy sweet clover hay high in dicoumarol. B Vitamin requirements—None, because no dietary B vitamins usually need to be supplied to cattle. Exceptions if ruminant system is adversely affected when an antagonist is present, or lack of precursors or other problems related to rumen health affect B vitamin synthesis.

Feed Containers

Separate your cattle, if necessary. Cattle that have different nutritional needs, based on body condition score, weight, sex, reproductive status, and stance in the pecking order, should eat separately. This is especially important if you have a herd that is diverse in different types of cattle. For instance, lactating cows won't do well on a ration that is suited for dry, mature cows. And growing steers and heifers could have a ration that could make a mature bull gain more weight than he needs going into the breeding season. Ideally a herd should be as uniform in nutrient needs as possible. It makes planning out what to feed and how to feed it easier. There's no avoiding having different groups of cattle to consider, like a group of bulls, a larger group of cows, some replacement heifers, and stocker steers, but to have a mix of cows especially that are in varying stages of lactation and gestation can make planning out rations harder than it needs to be.

Place the feed in appropriate containers. You can purchase containers for holding and feeding loose mineral, salt blocks, or grain for your animals. Most farm and ranch supply stores sell the kind of feeders you need. Hay feeders like cone or cylindrical feeders with slanted slots for the animals to fit their heads through are good for cattle. Hay feeders are ideal for reducing waste and to put large round bales in, and keeps the animals from climbing in and laying down in the feed and urinating/pooping in it further causing more waste. Large feed bunks that are not raised (typically those used in feedlots) are ideal for feeding silage. These bunks reduce waste apart from feeding silage on the ground, and prevents animals from laying in and pooping in the feed. You can limit how much silage is being fed in these bunks, because there's no need to fill it all up. Cattle can get really picky if they're fed too much silage, because they learn to pick through the more coarser material to get at the tastier grains. Use raised bunks for feeding cattle grain or supplemental mix apart from the hay or silage they're being fed to reduce waste and allow them to clean up as much as possible. Loose mineral should be fed in a sheltered unit where rain will not get into the feeder and ruin the mineral. Most farm and ranch supply stores sell mineral feeders, but you can make your own with things like an old rain barrel, a suspended tractor tire, a crafted wooden feeder, to even a modified futon or bed frame. Salt blocks can be put out on bare soil or grass, but should be put in a container that keeps it off the ground. An old tire rim, modified ATV tire with a flat iron or rubber bottom, or a purchased plastic or metal salt block holder can be used.

Consider making your own feed holders. While you can purchase all the pre-made containers you need, you can make your own (which may cost you less, not including labor) using various things around your home or your farm. Use things like 1 or more rain barrels, an old tire, a re-modified futon frame, large 4 inches (10 cm) PVC pipe, weeping tile, old flat-bed wagons, or anything else you can think of. With a bit of outside-the-box thinking and know-how with the tools you need, you can make anything you need to make for your animals. A tractor tire can be set vertical on a frame that stabilizes and elevates it for dispensing pellets or grain at set intervals as its pulled along by a vehicle or a horizontal-set ATV tire with a rubber bottom for holding a salt block. A 4 inches (10 cm) PVC pipe can be used for dispensing mineral that calves or cows lick. These feeders are gravity fed from an enclosed barrel or 5-gallon pail. You can even just craft traditional feeders yourself using wood planks and/or welded steel or iron frames. Just make sure that it's solid enough that it can take a lot of abuse from multiple hungry, jostling, feisty 1400 lb muscular bovines, but portable enough that you can move it around easily yourself without any trouble. Repairs are never going to be a matter of if (only when). Take into account how much space is needed for each animal and how high or low to the ground these feeders need to be. For example, 8 inches (20 cm) space for most cattle, and around 36 inches (91 cm) high from the ground to the top of the feeder.

Feed according to your calculations. Once you know the type of cattle you have, their daily intake, their nutrient requirements, and their average daily gain (if you are feeding growing cattle), then you can form a diet based on where you live, what's available and what you wish to feed them. Of course, what you should use to feed your animals is just as important.

Forage should always be the primary feed for any cattle. Forage comes in the form of pasture, hay, or silage. What species that are in the mix depends on your area and what's available. You can have pasture and hay forage that is all grass or all legume or a mix of both. Silage is primarily grass-based. No matter what class or production-type of cattle your feeding, forage needs to be the most important part of the ration. This is so that it stimulates rumination, chewing, and buffering capacity of the rumen. Even feedlot cattle should have a dominantly forage ration that is largely high-quality silage with grain, grain by-product and other supplement mixed in. Cattle raised for DIY home slaughter do not need to be on a similar diet, rather free-choice pasture and/or hay (high quality) with 2% of body weight of grain as-fed per day. Pasture and/or hay forage or fodder is the best type of feed for your cattle, provided it contains enough nutritive value for your cattle to thrive off of. If not, please take note of the nutritive deficiencies and supplement according to your animals needs.

Diet Maintenance

Balance the ration and supply supplementation when necessary. If the hay is too low in quality, supplement with range cubes, grain, protein tubs or molasses licks to satisfy their needs for more energy and/or protein. If pasture or hay is good to excellent quality, there will be less to no need for any supplements to be supplied. However, salt and mineral must be readily accessible to cattle at all times.

Keep track of body condition. Keeping track of weight gain or loss and general response to a the type of feed you give to your cattle will help you maintain them throughout the year. Also keep track of your cows requirements based on their reproductive cycles. You may need to change what you're feeding when its necessary according to what's available and what's not, and what your animals need. Remember, any drastic changes to feeds needs to be made gradually, like if you are switching from hay to silage or from coarse hay to pasture.

Keep water and loose mineral accessible to them at all times. Water, salt and mineral is a very important part of a bovine's diet. Water should be clean and clear. If watering out of a dugout, have a piping and dugout-enclosure system that eliminates the animals from going into and fowling the water, and diverts them to a more cleaner system farther away. Salt and mineral should be off the ground and (typically) sheltered from the elements to reduce waste. This more so with loose mineral than blocks.

Adjust your feeding seasonally. Don't let your animals go into winter thin and test your feed before going into winter feeding. This way you know in advance whether you will need to supplement your cows in the wintertime or not.Your feed costs will increase drastically and so will your changes of losing these animals from a) cold stress or b) poor feed.

Do not suddenly switch diets on cattle. This is especially important when switching from hay to grain. Also, introduce grain or any high-energy diet slowly (at a rate of only 1 to 2 pounds (0.45 to 0.91 kg) per day) to avoid bloat, grain-overload, or acidosis. Acidosis is a common malady, caused when the diet is switched so rapidly that the microflora in the rumen have no time to "switch over." This causes a sudden decrease in pH level in the rumen and encourage lactic acid-producing bacteria to increase in population, further decreasing pH in the rumen. The animal will go off feed, have stinky grey foamy diarrhea, and can even die. Bloat is another malady that is dangerous to cattle when suddenly switched diets. Bloat is when the rumen is unable to release the gases that are formed from the process of fermentation, and cause discomfort to the animal, and even presses on the lungs and diaphragm leading to death by asphyxiation. Bloat needs to be treated immediately to avoid such consequences.

Comments

0 comment