views

X

Research source

Amblyopia often runs in families. It is a treatable condition if it's caught early, but can cause vision loss if left untreated.[2]

X

Trustworthy Source

Mayo Clinic

Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals

Go to source

While in some cases a lazy eye is obvious, it can be difficult to spot in some children. Sometimes, even the child is not aware of the condition. An ophthalmologist or optometrist should be consulted as early as possible to diagnose and treat amblyopia. You can use some techniques to determine whether your child may have lazy eye, but you should always consult an eye care professional (preferably one who has training in children’s eye care).

Checking for a Lazy Eye

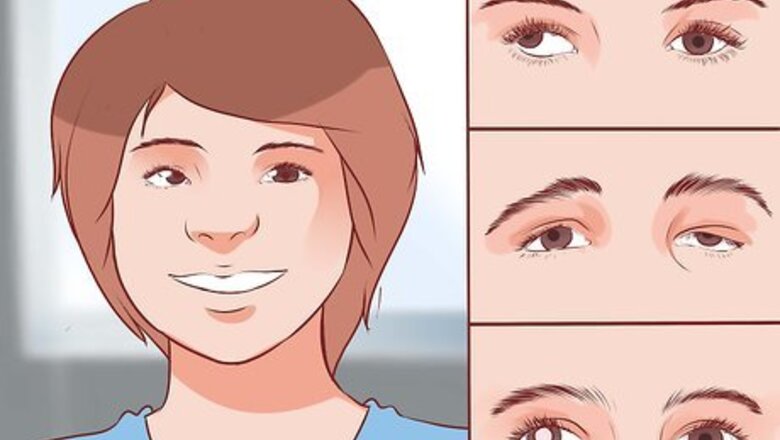

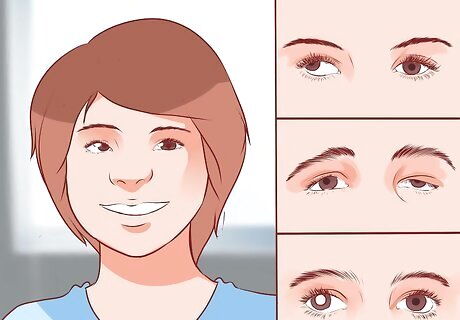

Understand what can cause a lazy eye. Amblyopia occurs when the brain has difficulty communicating with the eyes correctly. It may occur when one eye has significantly better focus than the other. On its own, amblyopia can be difficult to spot because it may not present with any visual difference or deformity. A visit to the eye doctor is the only way to accurately diagnose a lazy eye. Strabismus is a very common cause of amblyopia. Strabismus is a misalignment of the eyes where one eye turns inward (esotropia), outward (exotropia), up (hypertropia), or down (hypotropia). It is sometimes known as a “wandering eye.” Eventually, the “straight” comes to dominate the visual signals to the brain, causing “strabismic amblyopia. However, not all lazy eyes are associated with strabismus. Amblyopia may also be the result of a structural problem, such as a droopy eyelid. Other problems in the eye, such as a cataract (a “cloudy” spot in the eye) or glaucoma, can also cause a lazy eye. This type of amblyopia is called “deprivation amblyopia” and usually must be surgically treated. Severe differences in the refraction between each eye can also cause amblyopia. For example, some people are nearsighted in one eye and farsighted in the other (a condition known as anisometropia). The brain will choose one eye to use and will ignore the other. This type of amblyopia is known as “refractive amblyopia.” Occasionally, bilateral amblyopia can affect both eyes. For example, an infant may be born with cataracts in both eyes. An eye care professional can diagnose and provide treatment options for this type of amblyopia.

Look for common symptoms. Your child may not complain about his or her vision. Over time, a person with amblyopia may become used to having better vision in one eye than the other. A professional eye exam is the only way to determine for sure whether your child has a lazy eye, but there are some symptoms you can look for. Becoming fussy or upset if you cover one eye. Some children may become fussy or upset if you cover one of their eyes. This could be a sign that the eyes are not sending equal visual signals to the brain. Poor depth perception. Your child may have trouble with depth perception (stereopsis) and may also have trouble seeing movies in 3-D. Your child may have trouble seeing distant objects, such as a chalkboard at school. Wandering eye. If your child’s eyes appear misaligned, she may have strabismus, a common cause of amblyopia. Frequent squinting, eye rubbing, and head tilting. These may all be signs of blurry vision, which is a common side effect of amblyopia. Difficulty at school. Sometimes, a child may have difficulty at school due to amblyopia. Speak with your child’s teacher and ask whether your child is making excuses when asked to read from a distance (e.g., “I feel dizzy,” or, “My eyes are itchy”). You should ask your eye care professional to check for misalignment or vision problems in children younger than six months. At this age, your child’s vision is still developing so much that at-home tests may be ineffective..

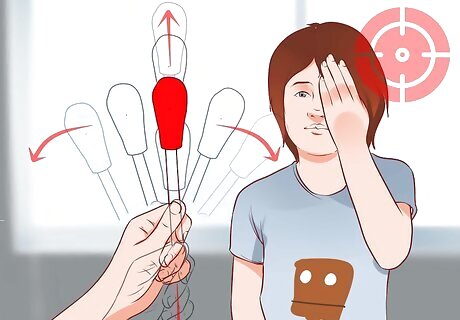

Do a moving object test. Test your child's response to movement to see if one eye responds more slowly than the other. Find a pen with a bright cap or a brightly colored object. Ask your child to focus on a specific part of the object (e.g., the pen cap, the “pop” part of a lollipop). Ask the child to focus on the same part of the object as he follows the colored object with his eyes. Move the object slowly to the right and then to the left. Then, move it up and down. Observe the child’s eyes carefully as you move the object. You should note if one eye is slower than the other while following the object. Cover one of your child’s eyes and move the object again: left, right, up and down. Cover the other eye and repeat the test. Make note of how each eye responds. This will help you determine if one eye is moving more slowly than the other.

Do a photo test. If you believe that your child's eyes are misaligned, it can help to check by examining photographs of the eyes. Working with photos gives you more time to scrutinize the indicators that may signal a problem. This is especially useful for infants and young children, who may not keep still long enough for you to examine their eyes. You can use existing photos if they show the eyes in clear detail. If you don’t have any photos that are suitable, ask someone to help you make some new photographs. Use the reflection from a small penlight to help rule out a lazy eye. Ask your assistant to hold a small penlight about three feet from your child’s eyes. Ask the child to look at the light. As the light is shining on your child’s eyes, take a picture of the eyes. Look for symmetrical reflection of the light in their iris or pupil area. If the light reflexes are in the same spot on each eye, then your child’s eyes are likely straight. If the light reflexes are not symmetrical, then one eye might be turned inward or outward. If you're unsure, take multiple photos at different times to recheck the eyes.

Do a cover-uncover test. This test can be used with children who are six months or older. The cover-uncover test can help determine if their eyes are properly aligned and working in equal measure. Have your child sit facing you or have her sit on a partner's lap. Gently cover one eye with your hand or a wooden spoon. Ask the child to look at a toy with the uncovered eye for several seconds. Uncover the covered eye and watch how it responds. Check to see if the eye snaps back into alignment because it drifted away. This can indicate an issue that should be checked by a pediatric ophthalmologist. Repeat the test on the other eye.

Visiting a Pediatric Eye Care Professional

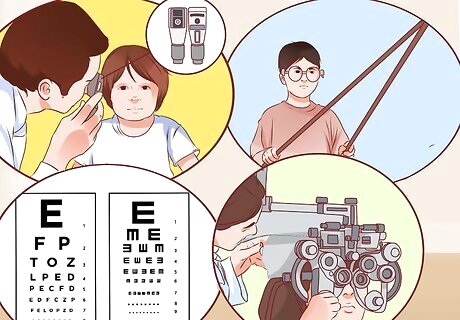

Locate a pediatric ophthalmologist. A pediatric ophthalmologist is a medical doctor that specializes in children’s eye care. While all ophthalmologists can treat pediatric patients, doctors with a pediatric specialty are highly trained in various eye disorders in children. Search online to find a pediatric ophthalmologist in your area. The American Optometric Association has a search feature that can help you locate an eye doctor in your area. The American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus also has a doctor locator. If you live in a rural or small city, you may need to look in a nearby city to find a specialist. Ask friends and family with children for recommendations. If you know people who have children with vision trouble, ask them to recommend an eye doctor. This may give you a sense of whether that doctor will be right for you. If you have health insurance, make sure that you choose a provider who is covered by your insurance plan. If you aren’t sure, you can contact your insurance company to verify whether they will cover the eye doctor you’re considering.

Familiarize yourself with some testing tools and exams. An eye care professional will assess your child’s eyesight and condition of the eyes themselves to determine if your child has a lazy eye. Understanding these will help you feel more comfortable during your visit. This will help you make your child feel more at ease as well. Retinoscopy. The doctor may use a handheld tool called a retinoscope to examine the eye. The retinoscope shines a light into the eye. As the beam moves, the doctor can determine the refractive error (e.g., nearsighted, farsighted, astigmatism) of the eye by watching the retina’s “red reflex.” This method can be very helpful in diagnosing tumors or cataracts in infants, too. Your doctor will likely use eye-dilating drops to examine your child with this method. Prisms. Your eye doctor may use a prism to test the eye’s light reflex. If the reflexes are symmetric, the eyes are straight; if they are not symmetric, the child may have strabismus (a cause of amblyopia). The doctor will hold the prism over one eye and adjust it to determine the reflex. This technique is not as accurate as some other tests for strabismus, but it may be necessary to use when examining very young children. Visual acuity assessment testing (VAT). This type of testing includes several types of exams. The most basic uses the familiar “Snellen chart,” where your child will read the smallest letters he can on a standardized letter chart. Other tests may include light response, pupil response, the ability to follow a target, color testing, and distance testing. Photoscreening. Photoscreening is used in pediatric vision exams. It employs a camera to detect vision problems such as strabismus and refractive errors by examining light reflexes from the eye. Photoscreening is especially helpful with very young children (under age three), children who have difficulty sitting still, non-cooperative children, or children with disabilities such as Nonverbal Learning Disorder or autism. The test usually takes less than one minute. Cycloplegic refraction test. This test determines how the eye structure displays and receives images from the lens. Your eye doctor will use eye-dilating drops to perform this test.

Tell your child what to expect. Young children may feel frightened in new situations, such as a doctor visit. Telling your child what may happen during her eye exam may help soothe and reassure her. It may also help her behave appropriately during the exam procedures. When possible, ensure that your child is not hungry, sleepy, or thirsty when you take her to the eye doctor, as these things can make the child fussy and more difficult to examine. The doctor will likely use eye-dilating drops to dilate your child’s eyes. This will help determine the level of refractive error in her eyesight during exams. The doctor may use a flashlight, penlight, or other light tool to help him observe light reflexes in the eyes. The doctor may use objects and photographs to measure eye motility and misalignment. The doctor may use an ophthalmoscope or similar equipment in order to assess if there is any eye disease or abnormalities in the eye.

Make sure your child feels comfortable with his eye doctor. If your child does have vision problems, he will probably spend a lot of time at the eye doctor’s office (or what feels like a lot of time to a child). Children who wear glasses will need at least an annual checkup. Your eye doctor and child should have a pleasant rapport (way of interacting). You should always feel as though your child’s doctors care about your child. If the eye doctor you have initially chosen is not willing to answer questions and communicate with you, find another. You should not feel rushed or harassed by any doctor. If you had to wait an excessively long time, felt rushed through an appointment, or felt like the doctor considered you a nuisance, don’t be afraid to try out another doctor. You may find one who suits your needs better.

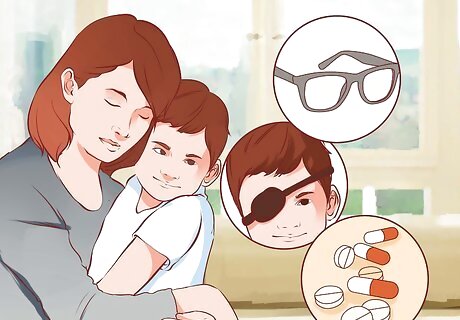

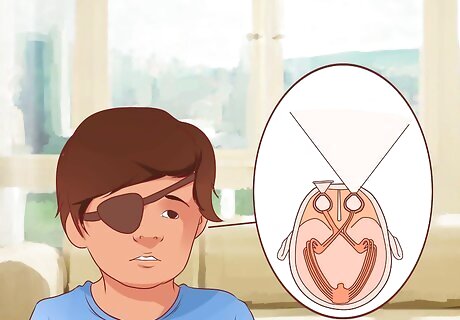

Learn about different treatments. After examining your child’s eyesight, the ophthalmologist can make recommendations about the appropriate treatments for your child. If the doctor has determined that your child has a lazy eye, therapies might include glasses, an eye patch or medication. It is possible that the doctor will suggest eye muscle surgery to realign the eye muscles to their proper position. This procedure is done under general anesthesia. The child will be given general anesthesia. A small incision will be made on the eye and an eye muscle will either be lengthened or shortened, depending on how the lazy eye needs to be corrected. Patching may still be required.

Treating a Lazy Eye

Put a patch over the good eye. Once the cause of amblyopia has been determined, patching will usually be part of the recommended treatment to force the brain to start seeing with the weaker eye. For example, even if surgery has corrected vision issues such as refractive amblyopia, patching may still be required for a short time to force the brain to start recognizing visual signals it had previously ignored. Ask for sample patches from your eye doctor. For patching to work, the patch must cover the eye entirely. Your eye doctor can ensure a proper fit. You can usually choose an elastic-band patch or an adhesive patch. The Amblyopia Kids Network has reviews of various eye patches, as well as information on where to purchase them.

Have your child wear the patch for two to six hours a day. In the past, parents were advised to have their child wear the patch all the time, but more recent studies have found that children can improve their vision by wearing a patch for as little as two hours per day. Your child may have to build up to wearing the patch for the prescribed amount of time. Start with 20–30 minutes, three times a day. Gradually increase the time until your child wears the patch for the correct length of time every day. Older children and children with severe amblyopia may need to wear the patch for a longer period of time each day. Your doctor can recommend when and for how long your child should wear the patch.

Check for improvement. Patching can produce results within as little as a few weeks. However, it may take several months of treatment to see results. Check for improvement by retesting your child’s eyes monthly (or as recommended by your eye care professional). Continue to check for improvement monthly as the condition has been known to get better with treatments lasting six, nine, or 12 months. The response time will vary depending on the individual child (and how faithfully s/he wears the patch). Have your child wear the patch for as long as you continue to notice improvement.

Engage in activities that require eye-hand coordination. Getting your child's weak eye to work harder while the strong eye is patched will make treatment more effective. Initiate art activities that involve coloring, painting, dot-to-dots, or cutting and pasting. Look at pictures in children's books and/or read with your child. Ask your child to focus on the details in the illustrations or to work through the words of the story. Be aware that your child's depth perception will be reduced because of the patch, so toss games may be extra challenging. For older children, video games are being developed to coordinate children’s eyes. For example, software developer Ubisoft has been collaborating with McGill University and Amblyotech to produce games like “Dig Rush” that treat amblyopia. Ask your eye doctor whether this is an option for your child.

Stay in touch with your eye care professional. Sometimes, treatments do not work as hoped. Your eye care professional is the best person to decide that. Children are often able to adapt to situations. Staying in contact with your eye care professional will keep you aware of whether new options may emerge for your child’s treatment.

Considering Other Treatments

Ask your doctor about atropine. Atropine may be an option if your child is unable or unwilling to wear a patch. Atropine drops blur vision and can be used in the “good” eye to force the child to use the “bad” eye. They do not sting like other drops. Some studies suggest that eye drops are as effective or more effective than patches for treating amblyopia. Part of this effect may be because using the drops is often less socially stigmatizing for children than wearing a patch. Thus, children are more likely to cooperate with their treatment. These drops may not need to be used for as long as patching. Atropine drops do have possible side effects, so do not use them without first consulting with your child’s eye doctor.

Consider Eyetronix Flicker Glass treatment. If your child’s amblyopia is refractive, flicker glass treatment may be an effective treatment alternative. Flicker Glass glasses resemble sunglasses. They work by rapidly alternating between clear and “occluded” (obstructed) at a frequency prescribed by your eye doctor. They may be a good choice for older children, or children who have not responded to other treatments. This treatment works best for children with mild to moderate anisometropic amblyopia (i.e., amblyopia caused by eyes with different strengths). The Eyetronix Flicker Glass treatment is usually completed in 12 weeks. It is not likely to be effective if your child has previously tried patching to treat amblyopia. As with other alternative treatments, always consult with your child’s eye doctor before trying any treatment.

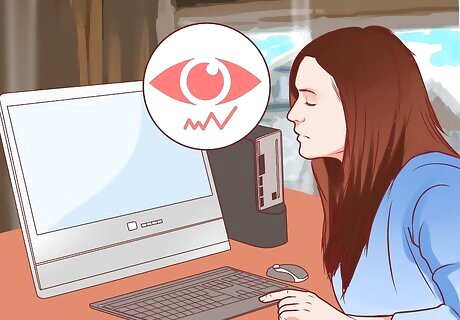

Consider RevitalVision for amblyopia. RevitalVision uses a computer to stimulate specific changes in your child’s brain to improve vision. The computer treatments (40 sessions of 40 minutes, on average) may be completed at home. RevitalVision may be especially helpful for older amblyopia patients. You will need to consult with your eye doctor to purchase RevitalVision.

Caring for the Eye Area

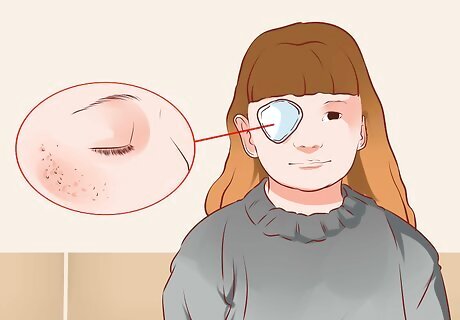

Monitor the eye area. The eye area can become irritated or infected during patching. Keep an eye on your child’s eye area. If you see rashes or cuts around the eye, consult with your doctor or pediatrician on how to treat them.

Reduce irritation. Both elastic band- and adhesive-style patches can irritate the skin around the eye and cause a slight rash. If possible, choose a hypoallergenic adhesive patch to reduce the risk of skin discomfort. Nexcare produces a line of hypoallergenic adhesive patches. Ortopad produces hypoallergenic patches in adhesive and glasses-fitting styles. You can also consult your child’s doctor for recommendations.

Adjust the size of the patch. If the skin under the adhesive part of the patch has become irritated, try covering an area around the eye that is larger than the patch with gauze. Attach the gauze to the child’s face with medical tape. Then attach the patch to the gauze. You can also try trimming away some of the adhesive part of the patch so there will be less of it touching the skin. The trick is to make sure that the normal eye is still completely covered and that the patch is secure.

Try a patch that can be attached to glasses. Since it won't come into contact with the skin, this style of patch prevents the problem of skin irritation. This could be a choice if your child has very sensitive skin. A patch that attaches to glasses can provide good coverage over the weak eye. However, you may need to attach a side panel to the glasses to prevent your child from trying to see around the patch.

Care for the skin. Wash the area around the eye with water to remove any traces of the irritant that may remain once the patch is removed. Use emollients or moisturizers on the affected area to help keep the skin moist. These will help the skin repair itself and help protect against future inflammation. Skin creams or ointments may reduce inflammation, but it's important to follow instructions carefully and not to overuse these products. In some cases, the best treatment is to do nothing and simply allow the skin to "breathe." Check with your physician for advice on treating your child's skin irritation.

Supporting a Child with a Lazy Eye

Explain what's going on. In order to make eye patch treatment successful, your child must keep it on for the prescribed amount of time. It'll be easier to get her to agree to this if she understands why she needs the patch. Explain to your child how it can help her and what might happen if she doesn’t wear it. Let your child know that wearing the patch will make her eyes stronger. Without frightening your child, let her know that not wearing the patch could cause result in worsened vision. If possible, let your child have input in scheduling her "patch time" each day.

Ask family members and friends to be supportive. Communication is the key to helping your child feel comfortable with patching. Children who feel self-conscious or embarrassed about wearing an eye patch are less likely to stick with the treatment successfully. Ask the people around your child to empathize and encourage him to stick to his course of treatment. Let your child know that he has several people he can turn to with any problems. Be open to answering questions your child may have. Let your family and friends know about the reasons for patching so they can support your child too.

Talk to your child's teacher or daycare provider. If your child must wear the patch during school time, explain the situation to the child’s instructor or caregiver. Discuss having the teacher explain to classmates why your child is wearing the patch and how they can be supportive. Make sure that the school officials and faculty are aware that teasing over the patch should not be tolerated. Discuss whether academic accommodations can be made for your child while she is wearing the patch. For example, ask whether teachers can give your child difficult assignments a little earlier, provide tutoring, offer a work plan, and/or check in with the student’s progress every week or so. These can all help your child feel more comfortable during patching and maintain good performance in school.

Provide comfort. Despite your best efforts, other children might tease your child or make hurtful comments. Be there to listen, soothe and reassure your child that this treatment is temporary and worthwhile. You could consider wearing an eyepatch in solidarity. Even if it’s just occasionally, your child may feel less self-conscious if he sees that adults can wear patches too. Offer eyepatches for dolls and stuffed animals too. Encourage your child to see the patch as a game, rather than as a punishment. Even if your child understands that the patch is for a good reason, he may see it as a punishment. Point out that pirates and other cool figures wear eye patches. Suggest your child compete with himself to keep her patch on. There are several children’s books that deal with patching. For example, My New Eye Patch, A Book for Parents and Children uses photographs and stories to explain what it will be like to wear an eye patch. Reading about others’ experiences may help normalize patching for your child.

Institute a reward system. Come up with a plan to reward your child when she wears the patch without complaints or difficulties. Rewards can help your child stay motivated to wear the patch. (Remember, young children don’t have a good sense of long-term rewards and consequences.) Post a calendar, chalk board or white board to keep track of your child's progress. Give small prizes like stickers, pencils or small toys when she has reached a certain benchmark, such as wearing the patch every day for a week. Use rewards as a distraction for very young children. For example, if your child pulls off the patch, replace it and give the child a toy or other reward to distract from the patch.

Help your child adjust each day. Every time your child puts the patch on, the brain needs about 10 to 15 minutes to adjust to having the strong eye covered. Lazy eye occurs when the brain ignores the vision pathway from one eye. Patching forces the brain to recognize those ignored pathways. This experience can be scary for children who are not used to it. Spend time with your child to comfort him. Do something fun during this time to help make the transition easier. Creating a positive association between the patch and a pleasant experience may make it easier for your child to handle the patching process.

Get crafty. If the patch is the adhesive type, let your child decorate the outside of the patch with stickers markers. Get a doctor's advice about the best decorations to use and how to apply them safely (you may not want to use glitter, for instance, as it could flake off and get in your child's eye). Never decorate the inside of the patch (the side that faces the eye). Design websites such as Pinterest offer a variety of ideas for decorating. Prevent Blindness also has suggestions on how to decorate patches. Consider hosting a decoration party. You can give your child’s friends novelty eyepatches to decorate. This may help your child feel less isolated during the patching experience.

Comments

0 comment