views

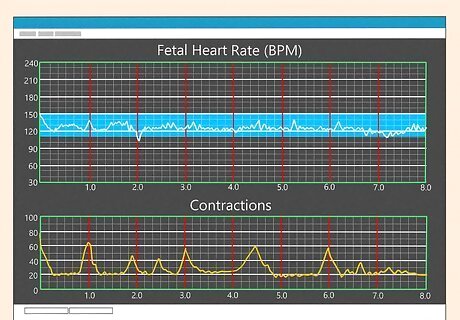

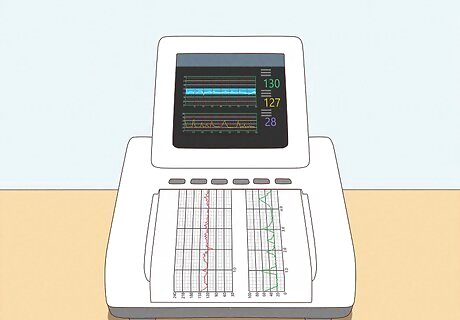

- An electronic contraction monitor displays 2 charts: 1 depicting your contractions, and another depicting your baby's heart rate.

- The X-axis on both charts indicates the time in minutes.

- On your chart, the Y-axis indicates contraction intensity. On the fetal heart rate chart, the Y-axis indicates your baby's BPM, or heartbeats per minute.

How to Interpret an Electronic Contraction Monitor

The monitor's graphs show the baby's BPM and your contractions. You’ll likely be continuously monitored from your hospital bed with the monitor beside your bed. On the screen there will be 2 graphs, 1 stacked on top of the other. Usually, the top graph will show the baby’s heartbeat, measured in BPM, or beats per minute, and the bottom one will show your contractions. The lines on the graphs move from right to left, meaning everything on the right is more recent. Because the charts are stacked, the baby’s heartbeats will line up with contractions that are occurring at the same time. If you're using an intermittent contraction monitor, your doctor will likely be there to interpret your chart, but when using a continuous monitor, you may be alone for a portion of the time. You may also receive printouts of the monitor’s recordings to interpret at home.

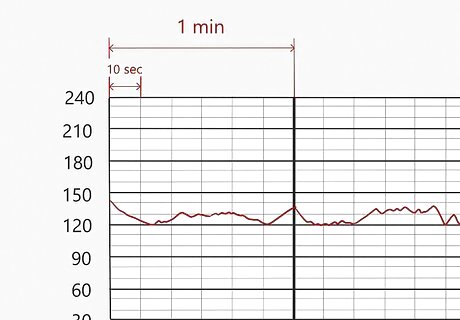

The X-axis times your contractions and your baby's heart rate. On both graphs, the X-axis—the horizontal line on the graph—indicates the time in minutes. As the lines representing the contractions and the fetal heartbeat move along the graph, you can use the X-axis to see how far apart each contraction or heartbeat is from the next. Each minute is depicted within bold lines, but between every minute are lighter lines measuring 10-second increments. There are 6 10-second sections for every minute. During labor, your contractions last around 30 to 70 seconds and usually come about 5 to 10 minutes apart. Contractions tighten the top of your uterus, applying pressure on your cervix; this causes your cervix to dilate and helps move your baby downward.

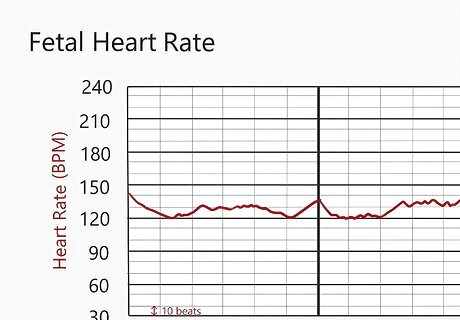

The Y-axis on the baby’s chart displays BPM. While the X-axis is the same for both charts, the Y-axis is different. The Y-axis of the baby's chart displays your baby’s heart rate in BPM, or beats per minute. The BPM are measured in increments of 10, with markings every 30 beats. A baby's BPM should be about 110 to 160, but minor fluctuations in BPM are normal. It can be scary to see your baby experience an abnormal BPM, but it doesn't necessarily mean there's a problem. Your doctor may perform tests just to be sure, and they may take certain steps to try to improve the BPM. Rest assured your doctor will try to do what's best for the health of you and your baby; in some cases, that may mean inducing labor, but it may be as simple as having you shift position to allow the baby more oxygen.

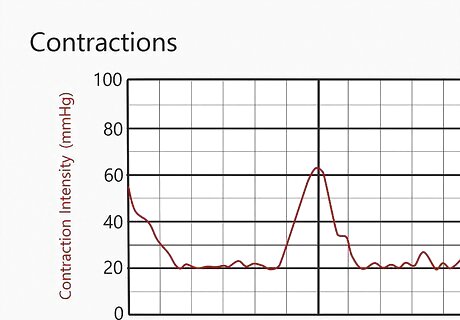

The Y-axis on your chart indicates contraction strength. On the contraction graph, the vertical Y-axis measures the intensity of your contractions in mmHg, or millimeters of mercury. The stronger the contraction, the higher the mmHg. Your contractions are represented as peaks or spikes. At the start of the active phase of true labor, the strength of a contraction is usually between 50 and 70 mmHg. The active phase is when your cervix dilates from 6 to 10 centimeters and your contractions become more intense, regular, and frequent. Once the cervix is fully dilated and you're ready to give birth, your contraction strength can reach 80 to 100 mmHg. Childbirth can be a beautiful, exciting, and meaningful experience, but it can also be scary and painful. You may be able to alleviate some discomfort or stress by doing some deep breathing, shifting position, or walking around, if you're able. Aromatherapy, soft music, soft lighting, and encouraging or soothing imagery, such as a family photo, can also assist in alleviating stress.

Types of Contraction Monitors

Continuous, or electronic A continuous contraction monitor, or an electronic contraction monitor, is the most common type. It measures the response of the fetus’s heart rate to contractions of the uterus, and displays the results continuously on a screen as you experience them. Every time you experience a contraction, it’ll be represented on the monitor as a peak—sort of like the peaks and valleys you’d see on a lie detector test. Continuous fetal monitors are usually external, but they can be internal, or both internal and external simultaneously. For external monitoring, a device known as an ultrasound transducer, also called a tocodynamometer, or a TOCO, is strapped over your belly to monitor the baby’s heartbeat, and a second monitor is placed over the top of your abdomen to measure your contractions. For internal monitoring, an Intrauterine Pressure Catheter, or IUPC, monitors the strength of your contractions. A tiny electrode is inserted into your vagina and positioned on the baby’s scalp to check their heartbeat. Your contractions will show up on the monitor even if you’re on an epidural and can’t feel them.

Intermittent, or auscultation Intermittent contraction monitoring, also called auscultation, refers to periodic, rather than constant, monitoring of the fetus. Intermittent monitoring is done with either a special stethoscope called a fetoscope or a device known as a Doppler transducer. Either device is pressed against your abdomen, allowing you to hear your fetus's heartbeat. Intermittent monitoring is more likely to be used during check-ups throughout low-risk pregnancies.

What type of contraction monitor is right for you?

Continuous monitoring is often used in labor and high-risk pregnancy. Because continuous contraction monitors present an ongoing record of your contractions and your baby’s heartbeat, they're a great tool to help you and your doctor check up on the health of your baby during high-risk pregnancies and other urgent situations to ensure you have the safest pregnancy possible. Intermittent monitoring is generally performed during routine physical check-ups throughout low-risk pregnancies, but keep in mind that your doctor may use a continuous contraction monitor even if your pregnancy is low-risk. Reasons you might need continuous or electronic contraction monitoring include: If you’re experiencing any fetal distress during labor. If you’re using an epidural. If labor is induced. If you have pre-existing medical conditions, such as hypertension or diabetes. If you’ve had previous children. If you’ve had a previous cesarean section. Some doctors prefer to use continuous monitors across the board, so if they recommend a continuous monitor, it doesn't necessarily mean something is wrong. If you have any concerns at all, though, be sure to ask your doctor for clarification or reassurance.

Comments

0 comment