views

Asking a Question and Researching

Start with a question. This question is not your hypothesis. Rather, it will give you a topic and let you start making tests and observations so that you can arrive at an educated hypothesis. The question should be about something that can be studied and observed; think about it as if you were preparing a project for a science fair. For example, a question could be something like, “Which brand of stain remover will remove stains from fabrics most effectively?”

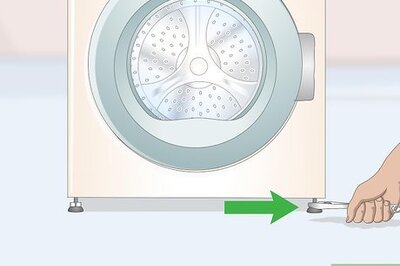

Develop an experiment to answer your question. The most common way to test a hypothesis is to create an experiment. A good experiment uses test subjects or creates conditions where you can see if your hypothesis seems to be true by evaluating a broad range of data (test results). For the stain-remover experiment, you could dirty 4 types of fabric (e.g. cotton, linen, wool, polyester) each with 4 different types of stains (e.g. red wine, grass, mud and dirt, grease), and then test the top four or five brands of stain remover (e.g. Mr. Clean, Tide, Shout, Clorox) to see which removes the largest number of stains.

Start gathering data to answer your question. At this point, you should start actually running your experiment. In any scientific test or hypothesis evaluation, a larger data pool will result in more accurate results. In the case of the stain-remover experiment, you’d need to purchase a bottle of each of the major stain-remover brands and dirty a variety of fabrics with a variety of stains. Then, test out each type of detergent on each of the stained fabrics. (If you live at your parents’ house, you’ll need to get permission to use the laundry room for most of a day.)

Making and Challenging Your Hypothesis

Create a working hypothesis. Your working hypothesis should be a statement about what you think is happening with what you’re observing. No starting hypothesis is 100% true, but it can be improved with continued testing. A good hypothesis should be your best guess after having conducted several initial tests. For instance, if you’ve run some loads of laundry (maybe testing which brand of stain remover works best on removing different stains from linen), you can use your results to take a stab at a hypothesis. A good working hypothesis would look like: “If fabrics are stained with common household items, Tide stain remover will remove the stains most effectively.”

Continue to perform more tests. Once you have a working hypothesis, you should continue to test in in order to improve your hypothesis. You’ll most likely find that your initial stab at a hypothesis was not entirely incorrect, but didn’t account for the full range of data. In our example, since you only tested 1 type of fabric (linen), you’ll need to repeat the laundry test with the other 3 fabrics (cotton, wool, polyester) and note which stain remover most effectively eliminates the stains.

Analyze the data that you’ve collected. In our example, once you’ve tested every combination of fabric, stain, and stain remover, you’ll have 64 individual results to look at. Look at all of the data that your experiment has produced (the results of how well each stain remover has removed each stain from each type of fabric). From here, you can draw a general inference from your analysis. While it can be tempting to only accept data that supports your hypothesis, it’s not scientific or ethical. You must accept all the data and watch for whatever patterns appear, even if it proves your hypothesis to be likely false. Note that significant results don’t mean your hypothesis is proven, but rather that based on the data you collected, the differences you observed are likely not due to chance.

Revising Your Hypothesis

Use inductive reasoning to note patterns among your data. This type of reasoning (also called “bottom-up” thinking) allows you to look for patterns and similarities in all of the data that you’ve observed. Let the data guide you as you make your hypothesis, and avoid deliberately misinterpreting data to support the outcome that you prefer. For example, if you began the experiment thinking that Tide would have the most effective stain remover, but you’ve noticed that Tide does a poor job of removing stains from red wine and mud, you likely need to change your working assumptions.

Make alterations to your hypothesis. If the data doesn’t support what you thought was true, then you can make a new hypothesis based on what you know now. This is a crucial part of the scientific method: everyone who tests a hypothesis should, by inductive reasoning, be able to revise their hypothesis according to the results that come from observing a large amount of data. So, if Tide turns out to be ineffective at removing certain types of stains, your early working hypothesis will have been incorrect.

Draw a revised hypothesis. Once you’ve tested, revised, and tested some more, you can draw a conclusion about your hypothesis. If your initial hypothesis needed improvement (or was flat-out wrong) now is the time to fix that. A good concluding hypothesis should incorporate what you learned from observing and analyzing the full body of data from your experiments. A final, tested hypothesis would look like: “Shout is the most effective stain remover for removing a variety of household stains from a variety of common fabrics.”

Comments

0 comment