views

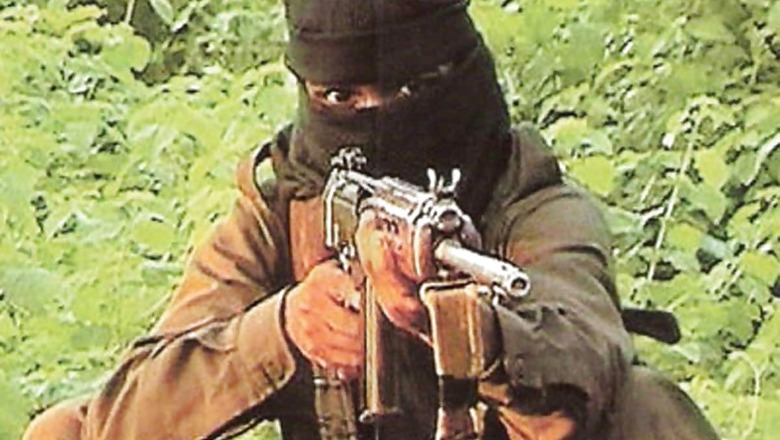

It was a daring leap of faith for 28-year-old Kalmu Raju, to leave the prospects of a well-paying job and return to his village to fight panchayat elections. It was a difficult choice, and not just professionally. He put his life at risk when he decided to fight the polls in Bastar’s Gangaloor area, which, because it was dominated by Maoists, hadn’t seen elections in the previous 15 years. In January this year Raju fought and won the election, becoming the sarpanch of a village in Bijapur area.

Raju is not alone. He is one among a new batch of people, Bastar’s own youth, who despite the adverse circumstances and unimaginable violence, went on to become engineers, lawyers and post-graduates in science. And when panchayat elections were announced, they returned to fight the polls and serve their villages. Local authorities say these young people “have raised the morale of the entire administration”. And Bastar’s Lok Sabha lawmaker Deepak Baij says these grassroots public representatives have turned the backward seeming place into “a beacon of hope for the entire state”.

News18 met six such young faces, who are quietly, despite being in the cross hairs of the Maoists, strengthening India’s democratic structure at its most fundamental level.

The journey so far has not been easy for any of these young public representatives. In the area from where Raju was elected, which comes under the list of places that have been marked as ‘highly sensitive’, Maoists have murdered 36 civilians in the last two months, three of which were public representatives. Twenty of these murders have happened in the past one month alone. Besides suffering this brutal violence, residents of this area are also forced to drink contaminated water, Raju told News18.

”In our area there is a huge problem of water contamination. The contaminated water does not only affect the health of people and the farm animals here. It also corrupts our farmlands, the area under cultivation. Facilities in the health and education sectors were almost non-existent when I took charge. I have been trying to work on these areas right now,” said Raju.

He wanted to go to a city to find a good job in the private sector, he admits, but changed his mind after returning to his village and observing the suffering of his people. So far, he says, he has been able to build a hospital with a capacity of 100 beds in his constituency which has three doctors on 24/7 rotating shifts.

”The hospital is helping the villagers a great deal, who otherwise had to travel 50 kilometres just to get to the district hospital in Bijapur to get basic health treatment. We have also enabled and put together a team of 25 local women who have started work on building an Anganwadi school and are going to be working on several other projects as well,” Raju told News18.

Several kilometres away from Raju’s village, in Kalyan district of Dantewada, Phooleshwar Mandavi, who also fought and won panchayat elections, is working in an area marked ‘highly sensitive’ because of Maoists’ dominance in the area. He is a postgraduate, MSc (Physics).

”My focus since getting elected has been to work on the education facilities in the area. The lack of solid educational facilities, I believe, has been the greatest source of weakness for our people. Because of being a ‘highly sensitive’ area my Bhuusa Raas block never got schools which resulted in most of the public remaining illiterate. I want to create a new model of education here,” 24-year-old Mandavi told News18.

As a public representative who wanted to develop educational facilities in the area, her biggest challenge was the lack of high-speed internet. She was forced to utilise the facility that she had – a dusty-old school building.

”When we started our classes we realised that we had been teaching, and we ourselves had been taught, the alphabet in a language that was incomprehensible. ‘A for Aeroplane’, for instance, doesn’t make sense to us because none of us has really seen an aeroplane. So we started reworking the syllabus. We taught them the alphabet with examples like ‘A for Arrow’, which the children could relate to,” Mandavi said.

She wants to save the children from the abyss of uncertainty; “anishchitta ki khai”, as she puts it. If the children of a place as backward as Bhuusa Raas get at par with the children of cities in terms of education, Mandavi says, “It could become a new self-sustaining model of development.”

Like Raju and Mandavi, Vimla Sori, who finished her LLB course from Jagdalpur last year, is a first-time public representative who is fighting battles on behalf of her people. In the case of Vimla, the main battle is to give ownership of land, where several generations of tribals have been practising farming, to the people.

”People here have for ages been expanding the cultivable land by going into forests, in order to get food and earn some money. But this land, which these people have cultivated with their blood and sweat, still on paper does not belong to them. If people get ownership of the land, it will bring a sea change in their lives. It will give them their deserved rights and help them rise out of poverty,” Vimla said.

Jitendra Sodi, a 27-year-old engineer, has been working among his people for the past five years. After winning the elections in January he has been trying to rebuild the schools that were demolished by Maoists. Shanti Mandavi, a graduate working in Jangala area of Bijapur, is trying to do the same thing.

Among the most vulnerable of this lot of public representatives is 22-year-old Rajesh Kumar Gota, who is a panchayat member Aadar panchayat area of Abujmarh, where Maoists are believed to have set up their base camp for the past several years. Gota, who is a diploma holder, also was elected to the panchayat through elections that were held in his area after 15 years. He says that setting up hospitals is his biggest priority, since women in labour find it very difficult to access health facilities in time of need.

The mere presence of these first-time public representatives has strengthened the hand of the local administration, officials say. Deepak Soni, the district magistrate of Dantewada, told News18, “We have seen a positive attitude in this batch of educated young panchayat members, which has raised the morale of the entire administration. We are planning to come up with several schemes to encourage these public representatives, to create a model out of this unique experiment.”

Alok Shukla, secretary, department of technical education, Chhattisgarh, told News18, “We are doing everything within our means to help the panchayat members in strengthening the education system. For instance in the challenging times of Covid-19, we decided to hold classes in Narayanpur district through loudspeakers as well as through the phone.”

The Lok Sabha representative of Bastar, Deepak Baij, described how the ground situation in an area believed to be among the most backward in the country, is changing through these young panchayat members. “We owe a great deal to our young people who, instead of pursuing lucrative career options in cities, decided to return to their villages and change the ground situation from within. Their commitment to the democratic system, their unity and their devotion towards the people has changed Bastar, from a backward place, to a beacon of hope for the entire state,” Baij told News18.

Comments

0 comment