views

Peter, 23, used to enjoy hitting Kampala's bars with his boyfriend until a draft bill dubbed "kill the gays" forced him into hiding.

"I'm so, so afraid. I just live indoors," he says, sitting in the semi-darkness of the cramped two-room dwelling where he has lived since his family and friends turned on him after the bill was introduced in 2009.

In this conservative east African country, the bill that initially proposed hanging gays has pitted veteran President Yoweri Museveni's government against two influential but opposing forces: the evangelical church and western donors.

Existing legislation already outlaws gay sex. The new legislation introduced by David Bahati, a backbench lawmaker in Museveni's ruling National Resistance Movement party, would go much further.

It would prohibit the "promotion" of gay rights and punish anyone who "funds or sponsors homosexuality" or "abets homosexuality".

Denounced as "odious" by US President Barack Obama, the first draft, which threatened the death sentence for what it called "aggravated homosexuality", languished in parliament for two years, never making it to the chamber's debating floor.

Bahati re-introduced a mildly watered-down second draft in February and is confident of a "yes" vote even though the bill's progress has stalled at committee level.

The death sentence clause is gone, as is the demand Ugandans report gays to the authorities, he told Reuters.

But the damage has been done, gay rights campaigners in Uganda say. A vitriolic homophobia is rising in Ugandan society, they say, pointing to the meteoric rise of the evangelical church as a driving force.

In the most recent clampdown, Uganda said last week it was banning 38 non-governmental organizations it accused of promoting homosexuality.

Two days before the announcement, police raided a gay rights conference outside Kampala, briefly detaining activists from around east Africa.

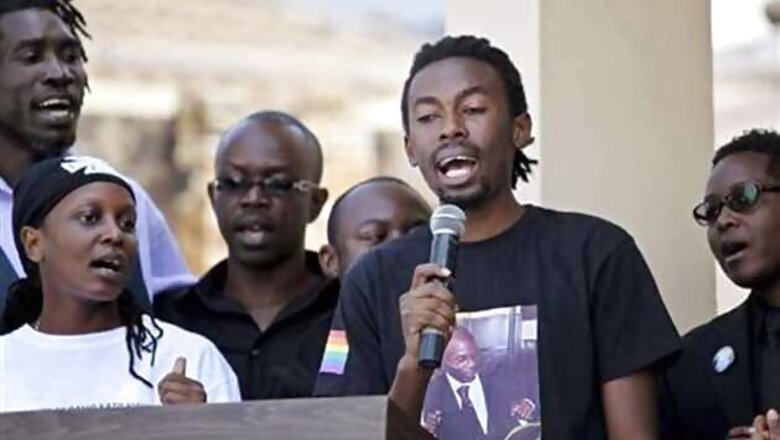

"Things were much better before the evangelical movement," said Frank Mugisha, director of the gay rights group Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG). He accuses Uganda's born-again pastors of spreading propaganda, including that homosexuals are "recruiting" young children.

EVANGELICAL INFLUENCE

Mugisha and other prominent gay rights campaigners say Bahati's initial bill was introduced directly after a March 2009 conference in Kampala that hosted representatives from the U.S. "ex-gay" movement.

US evangelical pastor Scott Lively, who spoke at the conference, said it focused on the "recovery from homosexuality" and warned Ugandans the gay movement sought to "homosexualise society" and undermine the institution of marriage.

Ugandan activists have filed a civil complaint against Lively in the United States, alleging he incited the persecution of gays in Uganda, violating international law.

A former lawyer who is now pastor of the Redemption Gate Missionary Society in Springfield, Massachusetts, Lively said his legal team has filed a motion to dismiss the complaint.

"The narrative of their case is that my speaking against homosexuality in Uganda led to a climate of hate and fear that led the government to take actions they wouldn't otherwise have taken," he told Reuters.

"The list of things they have put in their complaint do not amount to anything close to crimes against humanity."

Lively said he received a copy of the draft anti-gay bill from an anti-gay activist in Uganda ahead of its introduction, and disagreed with language included in it.

"It was very harsh," he said, referring to the proposal to execute homosexuals.

Lively, a reformed alcoholic who sees homosexuality as a "behavioral disorder" akin to alcoholism, said he sent back alternative language urging a focus on prevention and rehabilitation.

Some of Uganda's pastors have been some of the bill's most outspoken supporters.

"Would you accept that a thief should be licensed, that a prostitute should be licensed? There is no difference between a thief, a robber, a prostitute and a homosexual," said Pastor Joseph Serwadda, who heads Kampala's 6,000 member-strong Victory Christian Centre Church.

A wave of persecution followed the introduction of Bahati's bill.

One local publication, Rolling Stone, embarked on a campaign to out Ugandan gays, publishing photos of more than two dozen of them and their names, sometimes under the banner "Hang them".

"People didn't pay much attention before. When the bill came out, they started noticing gays," said Peter, whose three-year relationship ended when his partner became afraid to be associated with him after another tabloid outed Peter's roommate.

Peter's extended family called a meeting when they got suspicious.

"My sisters, my brothers, my aunties, my uncles, my grandpas, everybody needed me to change. They asked, 'What seduced you to do that?'," Peter said.

"(They said) if I didn't change from what I am to what they called normal, I should just get out of the family."

He withdrew from the outside world. Home alone for hours at a time, Peter reads the Bible he keeps by his bed for comfort. A wall decoration reads: "Jesus cares".

PRAYED FOR HELP

While the proposed legislation has pushed many like Peter underground, for others it had the opposite effect.

"Biggie" Ssenfuka knew she was attracted to women from the age of seven. When she read the word lesbian in a dictionary, she says she immediately recognized herself.

Raised a Christian, Ssenfuka prayed to God and fasted in a desperate bid to alter her sexuality. She burned every letter she had received from other girls and tried dating a man.

"But still I didn't change. I woke up and told myself this is life, be what you want to be and let people say what they want to say," said Ssenfuka, who sports dreadlocks and baggy, boyish jeans.

"People thought that homosexuals are these beasts ... they didn't expect people from next door," said Ssenfuka.

The 29-year-old finally came out of the closet in 2009 after the bill was introduced. "I said, now I am going to be open."

Still, activists like Ssenfuka are in the minority. The majority of gays are too afraid to go public.

Sitting in an open-air bar in Kampala on a Saturday afternoon is her girlfriend of one year, a woman with long braids who has children from a previous relationship.

Asked about her relationship with Ssenfuka, Patience was evasive. "I'm not exactly her friend," she said, and refused to elaborate.

Ssenfuka and Patience are careful not to act like a couple openly.

"It's tricky. You have to watch out, especially in public. You can't just kiss, you can't just touch and be happy," Ssenfuka said.

"BLACKMAIL"

The bill's floundering in parliament since 2009 signals Museveni is reluctant to proceed.

Stephen Tashobya, who chairs the parliamentary legal affairs committee tasked with scrutinizing the bill before a vote, said the committee had been "busy with other affairs".

"The president made general remarks sometime back, more than a year ago, (that) he didn't think that the bill was very urgent," Tashobya said.

The one-time rebel leader is widely regarded as a shrewd political operator who knows how to curry favor from Western powers, as he has by sending troops to Somalia, and when feathers ought not be ruffled.

John Nagenda, among Museveni's top advisers, told Reuters the president believed it was evil to indulge in homosexual acts.

"But on the other hand ... while he himself doesn't agree with it himself, he thinks that there must be a fair way of going about (things)," Nagenda said.

Museveni's gripe, Nagenda said, was with donors threatening to cut aid to impose moral values.

"It treats us like children," he said.

In October, British Prime Minister David Cameron threatened to cut aid to countries that did not respect gay rights. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton followed up in December.

"That is blackmailing, that is neo-colonialist and oppression. Attaching sharing of resources to a lifestyle of people is completely unacceptable," said Uganda's Minister of Ethics and Integrity Simon Lokodo.

"If you want to give (aid), you give it irrespective of our customs and cultures."

London appears to have since softened its rhetoric. The British High Commission in Kampala told Reuters in a statement that the UK government had no plans to cut aid in connection with the bill.

However, the statement also said Britain's diplomats were raising concerns over the proposed legislation "at the most senior level of the Ugandan government".

Bahati is optimistic his bill will prevail in parliament.

"There is no amount of pressure, no amount of dirty tricks, that will prevent the parliament of Uganda from protecting the children of Uganda," he said.

"We are not in the trade of values."

Comments

0 comment