views

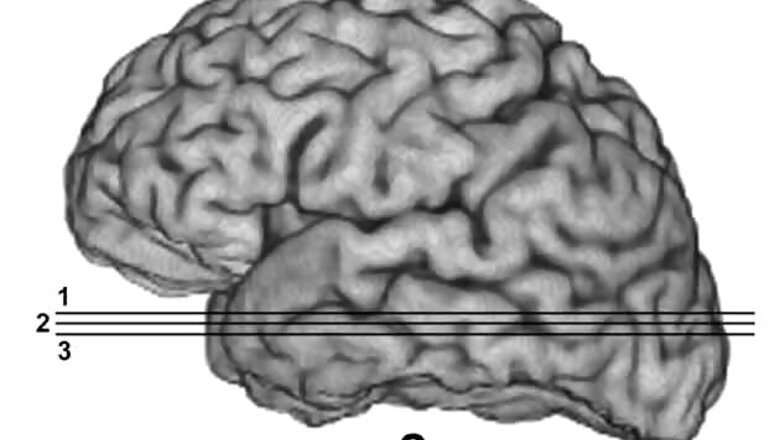

Washington: Women are able to carry higher levels of genetic defects without getting brain development disorders such as autism, a new study has found.

The study provides compelling evidence in support of the "female protective model", which proposes that women require more extreme genetic mutations than do males to push them over the diagnostic threshold for neurodevelopmental disorders, researchers said.

"This is the first study that convincingly demonstrates a difference at the molecular level between boys and girls referred to the clinic for a developmental disability," said study author Sebastien Jacquemont of the University Hospital of Lausanne in Switzerland.

"The study suggests that there is a different level of robustness in brain development, and females seem to have a clear advantage," Jacquemont said. Jacquemont teamed up with Evan Eichler of the University of Washington School of Medicine to analyse DNA samples and sequencing data set of one cohort consisting of nearly 16,000 individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Some of these people had autism spectrum disorders but they were not separated from the rest, 'ABC Science' reported. The defects researchers were looking for were large 'copy number variants' (CNVs) - sections of chromosomes carrying perhaps a dozen genes which are either missing, or present as multiple copies.

Surprisingly, the females in the sample had more CNVs than the males. Although both sexes in the study had neurodevelopmental disorders, the females were carrying a bigger 'burden' of genetic damage. Eichler said this fits with females somehow being better protected from the effects of the CNVs.

The team then focused on autism alone using a separate group of 762 families with autism spectrum disorders. The females in this group carried an even greater burden of CNVs. These women were also more likely to carry tiny harmful mutations, affecting just a couple of base pairs in the DNA, than the men in the group. "Overall, females function a lot better than males with a similar mutation affecting brain development," Jacquemont said.

"Our findings may lead to the development of more sensitive, gender-specific approaches for the diagnostic screening of neurodevelopmental disorders," he said. The study was published in The American Journal of Human Genetics.

Comments

0 comment