views

Nandita Das' second movie, Manto, like her first, Firaaq, talking about the pain and pathos which followed the 2002 Gujarat riots (some called it massacre, in which thousands perished), looks at four years during India's Partition and Independence from 1946 to 1950 through the eyes of one of the greatest writers of the subcontinent, Saadat Hasan Manto. Premiered at the ongoing Cannes Film Festival on Sunday, Manto was described to me by a friend and fellow journalist as the Garam Hawa of today's times, a movie made in early 1970s by M. S. Sathyu.

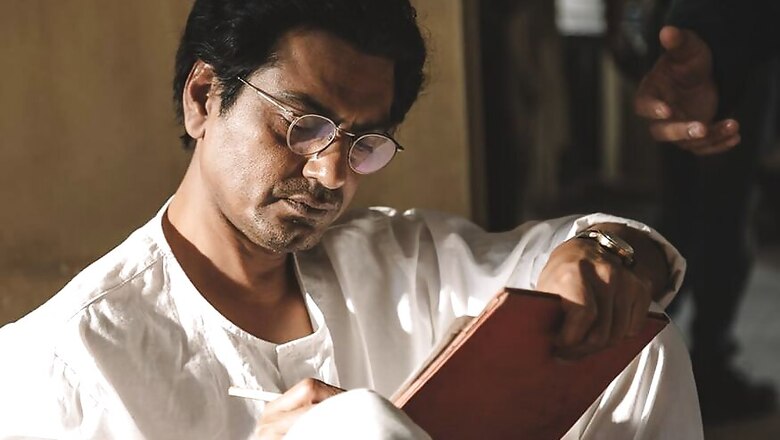

Comparisons may be odious, but it may not be fair to place both the films in the same slot. It may also not be quite right to compare the Garam Hawa protagonist, Balraj Sahani, with Nawazuddin Siddiqui, who certainly looks Manto, and infuses a degree of subtle strength into Das' work.

In fact, most of Das' cast is way above average: whether it is Raskia Duggal essaying the suffering wife of Manto or Tahir Raj Bhasin as the writer's close friend, Shyam, or even Rajshri Deshpandey (of S Durga fame) playing writer Ismat Chughtai, they all chip in with fine performances -- which could have in the hands of some other director turned into weepy, melodramatic affairs – so common in Indian cinema.

Manto manages to stay clear of an overdose of emotionalism, though India's Partition was an awfully painful process that uprooted thousands of men, women and children, often taking them away from what was their home for generations, taking them away from the familiar and the friendly.. This is what Das gets out best in her latest work, and Manto says time and again that he could never be the same if he were to leave his beloved Bombay. And that is where he grew up, where his father and mother and also his first son are buried. Bombay, for Manto, was the inspiration for some of the most powerful words that emerged from his pencil. He did not use a pen, though he was an avid collector of some of the most renowned brands of the writing instrument.

And out of his pencil flew the most brutal, the most acerbic words – words that said what he saw. And he saw some of the ugliest things, often the hostility towards prostitutes. And obviously, India and Pakistan, where Manto relocated, were the least equipped to handle such honest prose, which in one of the several court cases against Manto was finally given the tag of literature by a judge.

Several obscenity cases were slapped against Manto – much to the anguish of his wife – but till the end he continued to defend his own writings, calling them mirrors of society that exposed the ugly side of man. There is one heartrending scene of a child being taken away for the amusement of a few elderly/middle-aged men, and it was so disturbing to see the little girl playing on the seashore, oblivious of the leaching around her.

And this was one of the stories which Manto told his readers – a man who was a strange mix of courage and conviction, but overly wracked by sensitivity, which pushed him to take refuge in alcohol – straining his marriage (though Safia continued to stand by him) and forcing him to shirk his responsibility towards two of his young daughters. While one of them lays burning with fever, Manto is busy drinking, spending the few rupees he has on liquor, and not on medicines for her.

It was such a dichotomy that a man who was so attentive to the evils around him (the plight of prostitutes, for instance) was unbelievably callous towards his own wife and children.

Finally, when he sees the truth inside his home in Lahore, he decides to get rid of his addiction and admits himself into a mental hospital. But by then, his body had become a wreck, and he died, barely 42, leaving behind a rich legacy of extraordinary work, which minced no words while telling the truth.

Beyond all this, Das' work is a deeply moving narrative of how similar the world is today to Manto's times, how people are still getting uprooted and being turned into refugees, homeless and helpless. Manto felt the same pangs while leaving Bombay, a city he held dear. Till the end, he could never feel at home in Lahore, a place he was forced to flee when his best friend and actor Shyam, shaken by a Muslim attacking his cousin, blurts out to Manto that “even I could kill you”. Manto is shocked and shaken, and decides to get out of this atmosphere of hatred and violence.

Das must be lauded for creating a film which while talking about the desperation of Manto, underlines today's religious intolerance and geographical dislocations, placing them firmly well within the structure of her own outstanding work.

(Author, commentator and movie critic is covering the Cannes Film Festival for the 29th year, and may be e-mailed at [email protected])

END

Comments

0 comment