views

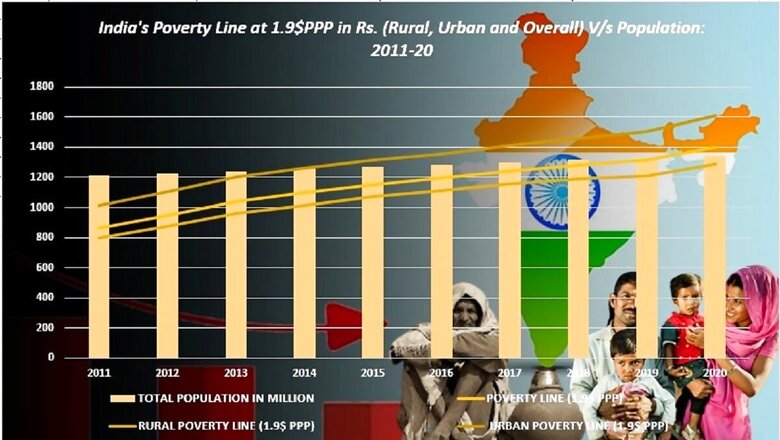

India’s poverty estimates have been a hot debate topic for quite some time now, with various agencies and individuals claiming different figures based on different computing methods. Recently, New York-based economist Karan Bhasin, along with Surjit Bhalla and Arvind Virmani, published all poverty-based estimates from the April 2021 IMF working paper at the state level in their paper named ‘State-Wise Poverty Estimates for India from Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality: Evidence from India’. The paper presents a quite progressive picture of India as far as poverty estimates are concerned. Here is what Bhasin says in an interview with news18.com. Edited excerpts:

What are some of the key findings and comments you would have with respect to India’s poverty estimates?

The Working Paper and subsequently the state-wise estimates were motivated by the lack of a recent consumption expenditure survey. In the absence of the survey, there were many claims that were made, in particular, related to the level of poverty and or pace of poverty reduction post-2011. What our data shows, and what even the World Bank authors’ April 2022 paper shows is that there is no evidence to argue that poverty did not decline since 2011.

The World Bank working paper stops its analysis in 2019, however, based on our estimates, we find two important things. First, there was not much increase in extreme poverty in India when one accounts for food subsidy transfers. Second, India’s extreme poverty line — the Tendulkar poverty line — is too low and it needs to be updated given that there are much less people under this poverty line than in 2011.

Since the present data is till 2020, as per your observations, how much change in poverty estimates can be seen during and post-pandemic?

Recent papers have found similar findings of no increase in poverty post the pandemic. This is not surprising given that the pandemic was a temporary shock and once that shock dissipated, household balance sheets improved. It is equally important to appreciate the strong policy support provided by governments to the people during the pandemic. That too, played an important role in absorbing a part of the economic shock.

How would you comment on India’s situation with other countries in terms of poverty estimates?

On the Living-Standards website, we intend to update gradually more data on fast-growing developing economies. However, one thing is certain — India remains the only large democracy to have successfully uplifted millions of people from extreme poverty at scale in recent memory.

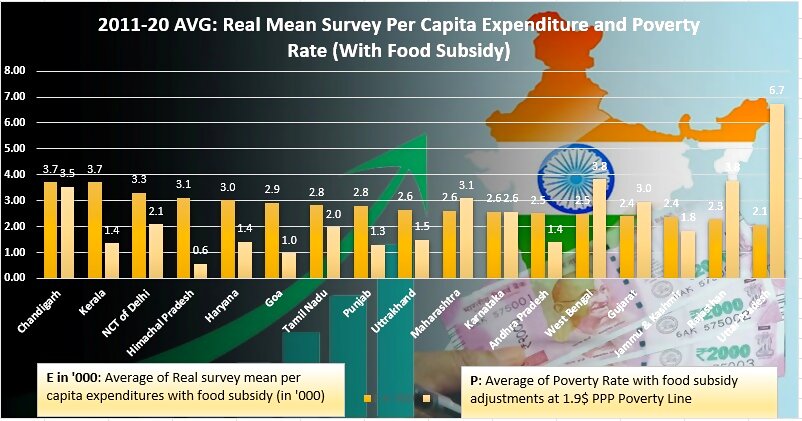

Given that now we have a state-wise bifurcation of the poverty estimates in India, which states as per you would be the role model for managing their poverty rate which other states should take an example from? And why?

The state-wise bifurcation of poverty estimates released on the Living-Standards website allows researchers to make use of these estimates and better understand how different states are contributing to poverty alleviation. There are several distinct models adopted by smaller states which have worked well for them, but they may not necessarily be appropriate for some of the larger and more populated states.

Peninsular states in general have done well on overall economic growth and improved standards of living and they would be a good model for larger and more populated states to emulate. Some resource-rich states can work on improving state capacity and encouraging private sector investment in those regions.

There are different papers on India’s poverty estimates like Rangarajan, Newhouse Vyas, Mehrotra and Parida, etc., which have huge differences in the poverty estimates made. How would you comment on this?

Several important points here. For starters, Newhouse and Vyas use the Uniform Recall Period method where households are asked to report their consumption over the last 30 days. They use what is the survey-to-survey imputation method to arrive at their poverty rate for 2014-15. Our URP-based estimates match well with their estimates for 2014-15 but it is important to stress that the Indian government adopted the MMRP, modified mixed recall period which is regarded as a more accurate method for capturing consumption, and the poverty estimates on the website are using the MMRP method.

The new survey was conducted in 2017-18, which has now been junked, and the ongoing consumption survey does not have a URP module. So, effectively, everyone will have to move to MMRP method going forward. Mehrotra and Parida used PLFS estimates and a recent paper by Arvind Panagariya documents how PLFS is not comparable with the NSS’ CES data from 2011. In any case, PLFS has a small consumption module, and it is not meant to capture consumption distribution. The ongoing survey and its results should hopefully help in concluding the second Great Indian Poverty Debate.

What according to you is the way forward for us at an organisation level and at the government level as well?

There are several policy choices that state governments should make given the success of reducing extreme poverty. Policy push towards faster economic growth is definitely desirable along with a recalibration of existing subsidy and welfare programmes to the poor in a more targeted manner.

Comments

0 comment