views

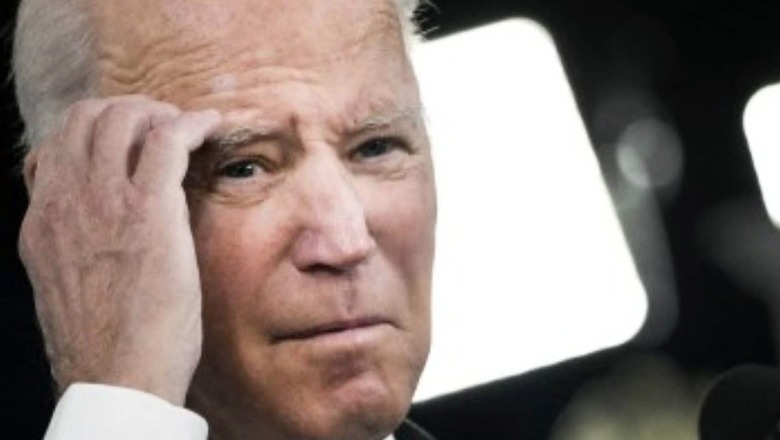

President Biden, as promised, has announced a Summit for Democracy on December 9 and 10 in order to “galvanise commitments and initiatives across three principal themes: defending against authoritarianism, fighting corruption, and promoting respect for human rights”. He is seeking once again to assert US leadership in promoting democracy and human rights worldwide although America’s own credentials on both fronts have been damaged by the exposure of the deficiencies of its own electoral process that were exposed during the last presidential election when the losing incumbent challenged the integrity of the election, called the result illegitimate and allegedly instigated his supporters to occupy and desecrate the Capitol Hill, and so on. Biden himself in his inaugural address acknowledged the depth of the crisis facing America’s democracy because of sharpened political polarisation and racism in society, the severity of the latter erupting subsequently in the Black Lives Matter movement.

Biden believes that he could take this initiative as he had reinvigorated American democracy by vaccinating 70 per cent of its population, passing the American Rescue plan, advancing bipartisan legislation to invest in its infrastructure and competitiveness, rebuilding alliances with America’s democratic partners and allies, rallying the world to stand up against human rights abuses, addressing the climate crisis, and fighting the global pandemic, including by donating hundreds of millions of vaccine doses to countries around the globe.

Many would be sceptical about some of these claims. The US still has not succeeded in controlling the virus in some parts of the country, its vaccine generosity has been late in coming and still leaves large parts of the developing world effectively untouched. Handing over the country to the Taliban that has scant respect for human rights, especially that of women and minorities, has been a failure on the human rights front. The Summit for Democracy is being convened at a time when the US still has not sufficiently removed the taints on the functioning of its democratic institutions and the fissures in its society. What also detracts from the impact of this initiative is the state of democracies in the West in general, the public sentiment about their having become dysfunctional and the sense of alienation this has bred, along with the growth of right-wing nationalism, both in the US and Europe.

US vs Russia and China?

The Summit for Democracy represents an enduring element of US foreign policy, namely, the promotion of democracy worldwide, almost as a crusade. The Cold War was fought as a struggle between democracy and communism. After the Soviet Union’s collapse and that of communism as an ideology, a triumphant US advanced its democracy agenda by regime changes in West Asia, the colour revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine and some Central Asian states and the Arab Spring phenomenon. In Venezuela and some other Latin American states, democracy promotion has been pursued with political and economic means. It is currently being pushed in Belarus.

The political motivation behind this democracy initiative is to forge a front under US leadership against authoritarianism, which essentially means China and Russia. Moscow has been under great pressure on democratic freedoms and human rights over treatment meted out to the political opposition as in the case of Alexei Navalny in particular, the prolongation of President Putin’s grip over power through constitutional amendments, LGTBQ issues and the like. China is under attack for its authoritarian model and violations of human rights of the Uighurs and Tibetans and suppression of freedoms in Hong Kong etc.

The US is now treating both Russia and China as adversaries. That China is presenting its model of political and economic governance as superior to that of western democracies for the developing countries is seen as a challenge. If the Summit for Democracy is intended to isolate China and Russia on democracy and human rights issues at the international level, that objective is hardly likely to be achieved. At the March 2021 meeting in Alaska between Secretary of State Antony Blinken and the Chinese Communist Party’s foreign affairs chief Yang Jiechi, the latter upbraided the former on the state of democracy and human rights in the US itself. At the November 2021 Biden-Xi virtual meeting, the Chinese president lectured the US president on the issue of democracy, reminding him that democracy was not mass produced with a uniform model for everyone, and that dismissing forms of democracy that are different from one’s own was in itself undemocratic.

China is not on the defensive on the issue of democracy or human rights. It has shown its clout both in the Human Rights Council in Geneva and the UNGA Human Rights Committee in New York when it mobilised support from a large number of countries, including several leading Islamic states, on the Uighur issue on which the US-led western countries sought to condemn China.

Nor is Russia defensive. Putin believes that “Russian democracy is the power of the Russian people with their own traditions of national self-government, and not the realisation of standards foisted on us from outside” and that “democracy cannot be exported to some other place. This must be a product of internal domestic development in a society”. In fact, Putin believes that the ideology that has underpinned Western democracies for decades has “outlived its purpose”.

Will This be a Moral Class?

Both Russia and China feel that the Summit for Democracy is a divisive initiative and they have criticised it. The Russian and Chinese ambassadors in the US have published a joint article in the publication The National Interest on November 26 calling the initiative a product of America’s Cold War mentality that is intended to stoke up ideological confrontation and a rift in the world and creating new “dividing lines”. It added that democracy can be realised in multiple ways, and no model can fit all countries. The article claimed that democracy is the fundamental principle of Russia’s political system and that the development of democracy there is closely connected to its culture and traditions.

The two ambassadors further said that democracy is not just about domestic governance; it should also be reflected in international relations, noting that “interfering in other countries’ internal affairs—under the pretext of fighting corruption, promoting democratic values, or protecting human rights… wielding the big stick of sanctions, and even infringing on their sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity go against the UN Charter and other basic norms of international law and are obviously anti-democratic.” They said further that “no country has the right to judge the world’s vast and varied political landscape by a single yardstick, and having other countries copy one’s political system through colour revolution, regime change and even use of force.” There is no need to worry about democracy in Russia and China, the ambassadors said, and called “on countries to stop using “value-based diplomacy” to provoke division and confrontation”.

America’s policies on the spread of democracy and protecting human rights have always been controversial as they are seen as marked by double standards and geopolitical objectives. The list of countries invited to the Summit reflects this criticism. The problem in drawing up such a list is that if one goes by strict selection criteria not many countries would be eligible, but if the criteria is not strict then those left out would feel doubly resentful, especially the leaders of those countries where the domestic opposition may use the exclusion to validate their accusation that the government was suppressing democracy at home. The US has invited 110 countries, with many anomalies. Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Bhutan have been excluded but Pakistan has been invited. Singapore, an ally and pivotal as a partner in ASEAN, has been excluded. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is in. Numerous island states have been invited for geopolitical reasons and not as examples of democracies: Tonga (population 106,000), St Kitts and Nevis (53,732), St Vincent and the Grenadines (110,000), St Lucia (184,000).

The net gain for the US to launch this initiative at this point in time is not too apparent. The US has announced that following a year of consultation, coordination, and action, President Biden will then invite world leaders to gather once more to showcase progress made against their commitments. Fighting corruption has also been included in the summit’s agenda. To seek commitments from participating countries implies that they would recognise their democratic and human rights deficit and promise improvement. Will this be a moral class?

Both the Summits “will bring together heads of state, civil society, philanthropy, and the private sector, serving as an opportunity for world leaders to listen to one another and to their citizens, share successes, drive international collaboration, and speak honestly about the challenges facing democracy so as to collectively strengthen the foundation for democratic renewal”. What will be the criteria for selecting civil society and private sector representatives? Will the US select them on behalf of other countries or it will be an open forum? Will the leaders have to listen to the criticism of elements of the civil society of their own countries in an international forum? These aspects of this initiative are unclear.

The author is Former Foreign Secretary. He was India’s Ambassador to Turkey, Egypt, France and Russia. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment