views

The Covid-19 outbreak has put immense strain on the government, hospitals and law enforcement machinery. Under severe stress, the frontline workers are almost on a round-the-clock duty. In several cases, government officials, medical personnel, and policemen have themselves become victims of the pandemic.

As India mulls over various options to relax or completely lift the ongoing lockdown in the orange and green zones, any hasty decision runs the risk of escalating the rate of transmission, putting further strain on these frontline Covid-19 fighters. In Maharashtra, the state with the highest number of Covid-19 cases in India, chief minister Uddhav Thackeray has hinted that he will ask the central government to provide additional manpower to give some temporary phase-wise relief to the strained police force.

Realising this ordeal, a community in rural Vaijapur, a sub-district of Aurangabad in hinterland Maharashtra, has taken the lead in easing the strain on the frontline workers. The entire population of Vaijapur, of 375,000, strictly followed the “stay home” guidelines, almost as if the whole area had agreed to an unwritten social contract, embracing a self-imposed curfew.

By just staying put in their respective homes, the people created an environment for the frontline workers to go about their duties peacefully and without any disruptions. And while overstressed and sleep-deprived pictures of healthcare professionals and policemen went viral on social media, these frontline COVID-19 workers in Vaijapur were able to take a much-needed break from their perilous duties.

On May 9 and 10, local citizens and civil society groups pitched in with voluntary work giving the men and women engaged in the administration’s frontline taskforce to have a rare weekend break.

For the two days when the civil society took over the essential services, all shops and establishments were shut. Police constables were replaced by 80 volunteers at eight check posts. Under the supervision of just one government doctor each, the OPD at the Vaijapur sub-district hospital and six primary health centres were taken over by private doctors from the area.

The healthcare volunteers were provided with masks and sanitisers, while the private doctors were given complete personal protection equipment (PPE) kits.

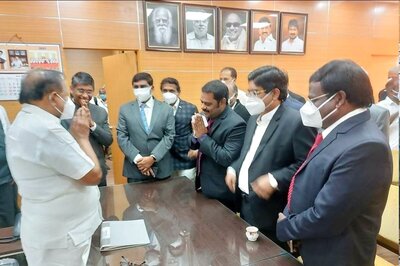

This unique participatory model was worked out by the people with help from the local legislator Ramesh Bornare. The entire planning of the model involved close collaboration with district officials and political workers from the district, municipal council, and panchayats. There were 3,000 WhatsApp groups created to reach out for emergencies and any distress calls.

Consisting of a big town of 60,000 people and 218 villages, Vaijapur itself does not have a single reported Covid-19 case. However, it is part of the Aurangabad district, which till May 11, had reported 602 cases and 14 deaths. Known as the Gateway to Marathwada, it is also a through point for migrants going from Mumbai towards North Maharashtra, which makes it vulnerable.

After this initial success, the model is slated to be tested on a larger scale and on two separate days of the week in Vaijapur, involving separate batches of community volunteers.

As the country prepares to brace for more difficult times despite partial relaxation of the lockdown and reactivation of the economy, the role of the community will gain even more importance in tackling the long-term effects of the outbreak. Vaijapur-like models will indeed provide the roadmap for the immediate future.

Internationally, Taiwan’s already existing neighbourhood warden system, which was put into use as a Covid-19 measure, received a lot of applaud.

The wardens, who are elected hyper-local representatives in small neighbourhoods, facilitated enforcement of the quarantines and helped deliver meals and other assistance to those who needed it.

A few Indian cities already have a well-established citizen participation system. The Area Locality in Management (ALM) groups in Mumbai and the Bhagidari groups in Delhi could be activated on the lines of the Vaijapur effort.

Already, there are several examples of housing societies and neighbourhoods pooling in to arrange for essential provisions, and these arrangements could be formalised by the urban local bodies. Like Vaijapur, several rural districts in India too have scores of citizens’ groups engaged in the drive to make villages open defecation-free under the Swachh Bharat Mission.

These networks must be considered to raise a small army of local citizen volunteers to become remote Covid-19 wardens. These volunteers could ensure that social distancing protocols are followed. With basic training, they can also supplement and complement the services rendered by the non-specialist front-line warriors.

There could be an initiative to create neighbourhood protocols that to could enable communities in mapping spaces for isolation, contact tracing, helping the vulnerable and high-risk groups. A second rung of healthy professionally-equipped volunteers could be listed who could move in to temporarily replace the frontline staff, if needed.

The government has done its bit to fight Covid-19, the private sector has pitched in with their individual and collective strength, and NGOs are working over-time to fulfil the community needs of food and shelter. Now it is the turn of the civil society to take over the baton and race ahead in this fight against Covid-19.

Comments

0 comment