views

Hope is ebbing away, a gnawing despair is increasingly eroding confidence in the system. If our governments and public administration do not recognize their inadequacies, many more people will die. Any crisis, especially a once-in-century one such as the current pandemic, can overwhelm and freeze decision-making; to survive the immediate becomes the only goal. But like in a war, a battle cannot freeze decision-making; to win the war, the preparation should be for the duration of the war and effort has to be multifold. There could be many reasons for the lack of preparation but nothing justifies the deaths due to lack of preparation.

The immediate future demands that there be a plan to manage the coming surge in rural and small towns. While the system is overwhelmed by the second wave in big cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, it is also time to prepare for the inevitable shift in this surge to other geographies as well as small-town India.

The objective should be to shift the decision-making to district, block and panchayat levels. Decentralization means the freedom to take decisions and fill the gaps on a war footing at the levels of: District Commissioner, Block Development Officer and Sarpanch.

Rope in Defence Forces

This contingency planning cannot be done in Delhi but should be led by the health secretary of states. They should not try micromanaging but should prepare the SOP for procurement and let the lower staff take the lead for the coming rural and small town surge. Flexibility at the local level should be given to meet the demands of an area. One size will not fit every district centre. The district administration should be allowed flexibility as well as seek it to reach out to defence forces in the vicinity for support. This local level delegation of decision-making is crucial now.

It’s important to align the defence forces, paramilitary units and home guards also to take over districts where the civil administration does not have the wherewithal to contain the virus upsurge. This has been done in the past; the Army has a well laid-down drill for a war-like situation. All that needs to be done is to customize it for a medical emergency. Egos should not come in the way. Hubris combined with the inability to learn from the experiences of other countries have caused the current crisis—a shortage of oxygen, medicine, beds, doctors, nurses and hospitals.

The shortage of healthcare services in small towns and rural areas is more acute than in big cities. With big cities drowning under patients, what will be the strategy for the larger population? What will happen if a small-town COVID patient with 2-3 caregivers each starts rushing to a big city looking for an ICU bed and oxygen? As of now, in cities, only Level 3 patients are being admitted under the three-level demarcation system for treating patients. The challenge in small towns and rural India will be larger. As both public and private sector healthcare services in small town India exist mostly in name, and certainly not with adequate supplies of oxygen, ventilators, doctors and nurses. State-owned district hospitals have poor infrastructure; they will not be able to withstand the coming second-wave tsunami.

The strategy of a better home isolation and treatment model with adequate support has to be developed on a war footing. Since civil administrations are not geared for war, district-wise COVID management must be handed over to the defence and paramilitary forces. The Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) has to be prepared to set up temporary COVID hospitals in remote districts where healthcare services are poor or non-existent. This has to be activated as quickly as possible at the ground level. We cannot wait for the surge in the small towns to further overwhelm the already overcrowded healthcare system in the cities. Punjab has already started coordinating with the Army and the Punjab health minister confirmed this to me in a conversation.

The oxygen shortage is a logistical problem: with the demand growing exponentially, the new plants that are being established will not come up overnight. The small plants will take up to 10-15 days and even more to set up. The capacity of each plant is important; every bed in every hospital should have an oxygen backup and every permanent bed capacity that is being created should have oxygen back-up. This is the minimum requirement. Until now, hospitals have avoided this extra expenditure to cut down capital costs; now that COVID will perforce make this a mandatory requirement in each hospital, the government should provide financial and tax incentives to hospitals so they don’t worry about this capital expenditure.

Shortage of critical drugs such as Remdesivir could be easily met by invoking compulsory licensing provisions and issuing government orders. While the impact of Remdesivir on COVID is not clear, it appears to be palliative for patients who think it will help them get well.

Vaccination Faces Capacity Challenge

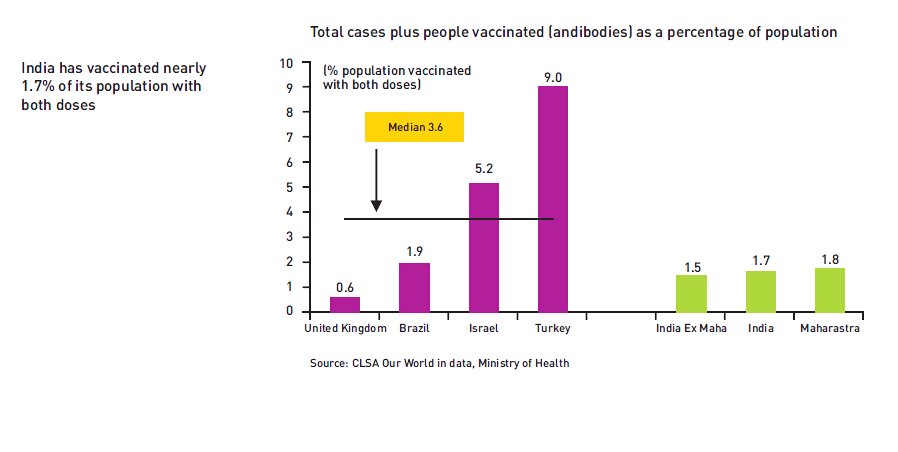

The second front on the COVID battle is the pace of vaccination. Currently, India is targeting 400 million vaccine shots by July 2021, according to a statement by Union Health Minister Harsh Vardhan. As on April29, India has administered 15,22,45,179 doses of the vaccine. Of these, only 2,67,58,250 people have been fully vaccinated, roughly accounting for 1.95 per cent of the total population. Additionally, we have only been able to achieve 13 per cent of the vaccination target.

Currently, India is administering two vaccines, Covishield by Serum Institute of India (SII) and Covaxin by Bharat Biotech. Recently, the government has also approved the import of Sputnik V. At the moment, India administers about 20 lakh doses every day, of which 90 per cent are of Covishield. At this rate, India will only be able to meet a little over half its target by July 2021. The country will have to increase its vaccination capacity to meet its modest target.

With the recent announcement of opening of vaccination for 18+ citizens from May 1, there is an evident shortage of vaccines in the country. To meet the targets, SII needs to increase its capacity to 90million, Bharat Biotech to 12million along with an intake of 50 million doses of Sputnik V every month. Although even in this case, we will fall short of the target.

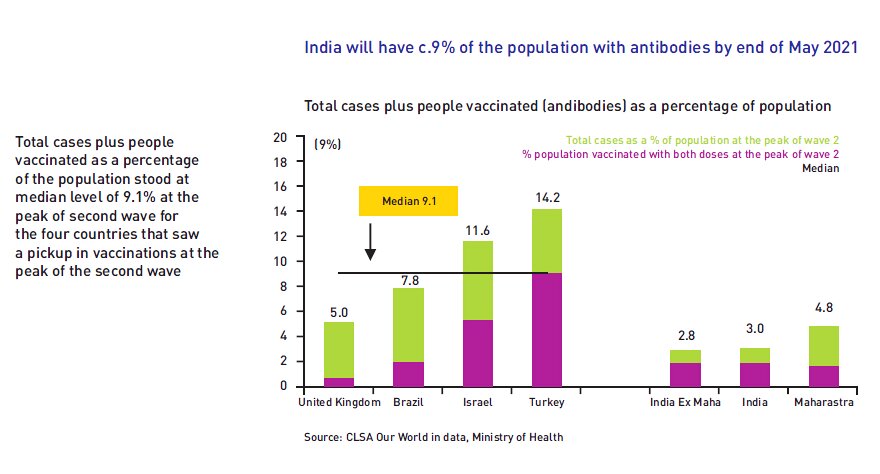

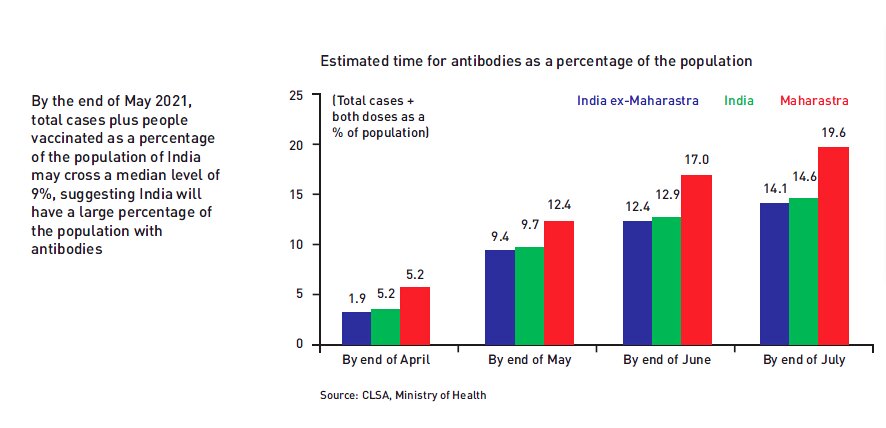

If you see the attached graph on the growth of the virus, experts believe that it has to infect at least 2 per cent of the population in an area before it starts peaking off. This means that it will start peaking off in Maharashtra soon but it is yet to reach that level in other parts of the country. Hence, to break this chain vaccination is the only way. As chart 1 shows, at least more than 9 per cent of the population has to be covered under vaccination for the second wave to stabilize. Israel, a small country, covered 11.6 per cent of its population during the second wave and was able to flatten the curve. Turkey covered 14.3 per cent of its population.

The country can develop a higher delivery capacity by first increasing the number of people at each hospital who can give a simple injection. Primary health centres can be roped in across the country as they have paramedical staff capable of giving injections. Every state is not even utilizing their full capacity nor can they increase it till they have a schedule for the delivery. Punjab is using one third of its capacity and is awaiting a full schedule so that it can scale up. This is the situation in every state.

The bottleneck is the limited manufacturing capacity of the existing manufacturers, as the drugs have been licensed by only two manufacturers in India. Instead of waiting for just two manufacturers to deliver, who are also controlling the supply chain, more companies should be allowed to manufacture. The government can either buy out the patent from Bharat Biotech or SII and go in for compulsory licensing. Compulsory licences are issued by governments after compensating patent holders for their intellectual property rights. Government has to negotiate quickly with global vaccine producers to enable compulsory licences for local production. It is important to ensure that patent holders of vaccines do not become the reason for the rising death rates in India.

Custom-built refrigerated mobile units could provide the shots in housing societies, RWAs, and locations that are not near formal facilities Now is not the time to bicker over patenting as vaccination is the only way to control the second wave and prevent a third surge. The next few months, as Chart 3 shows, are going to be crucial in managing the second wave as it will shift regions and begin its journey of death, mayhem and peaks in rural and small town India.

Rural and small town India needs a more exhaustive management and it cannot be centralised at state or central government level. Planning for adequate supply and delivery of oxygen, ICU beds, medicines and vaccination has to be done on a war scale. It is better to be over prepared now than to repent later.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment