views

X

Research source

Understanding Half-Life

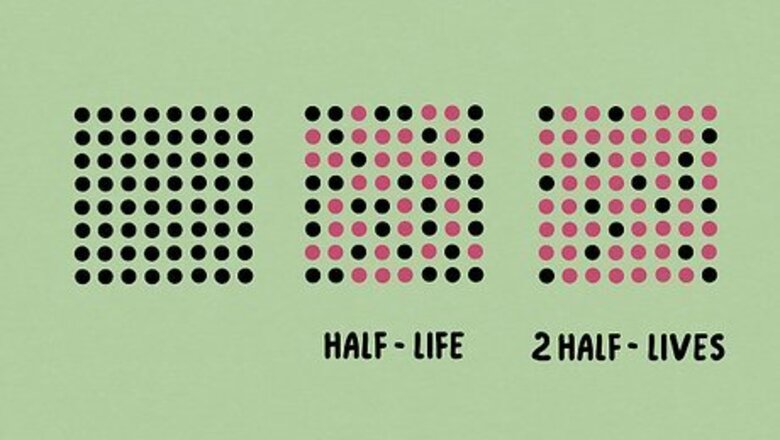

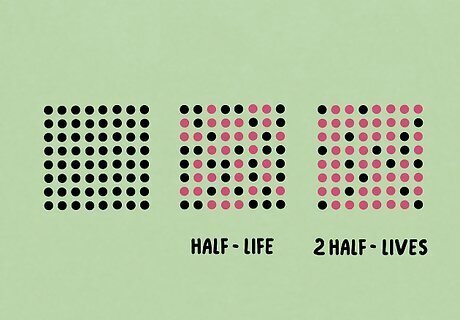

What is half-life? The term “half-life” refers to the amount of time that half of the starting substance takes to decay or change. It’s most often used in radioactive decay to figure out when a substance is no longer harmful to humans. Elements like uranium and plutonium are most often studied with half-life in mind.

Does temperature or concentration affect the half-life? The short answer is no. While chemical changes are sometimes affected by their environment or concentration, each radioactive isotope has its own unique half-life that isn’t affected by these changes. Therefore, you can calculate the half-life for a particular element and know for certain how quickly it will break down no matter what.

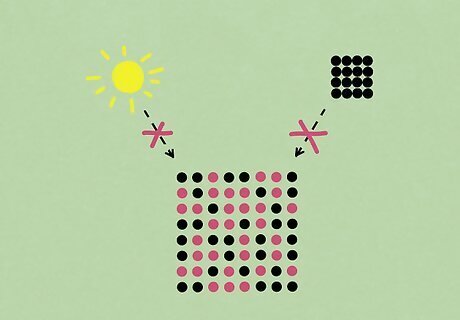

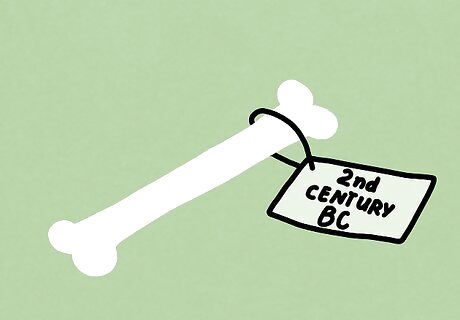

Can half-life be used in carbon dating? Yes! Carbon dating, or figuring out how old something is based on how much carbon it has, is a very practical way to use half-life. Every living thing intakes carbon while it’s alive, so when it dies, it has a certain amount of carbon in its body. The longer it decays, the less carbon is present, which can be used to date the organism based on carbon’s half-life. Technically, there are 2 types of carbon: carbon-14, which decays, and carbon-12, which stays constant.

Learning the Half-Life Equation

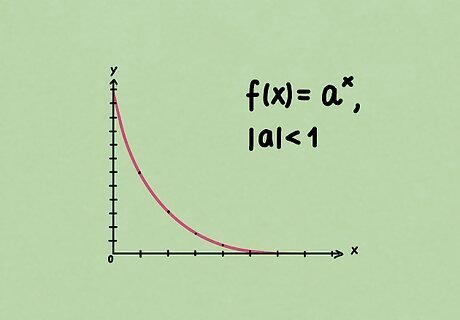

Understand exponential decay. Exponential decay occurs in a general exponential function f ( x ) = a x , {\displaystyle f(x)=a^{x},} f(x)=a^{{x}}, where | a | < 1. {\displaystyle |a|<1.} |a| In other words, as x {\displaystyle x} x increases, f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} f(x) decreases and approaches zero. This is exactly the type of relationship we want to describe half-life. In this case, we want a = 1 2 , {\displaystyle a={\frac {1}{2}},} a={\frac {1}{2}}, so that we have the relationship f ( x + 1 ) = 1 2 f ( x ) . {\displaystyle f(x+1)={\frac {1}{2}}f(x).} f(x+1)={\frac {1}{2}}f(x).

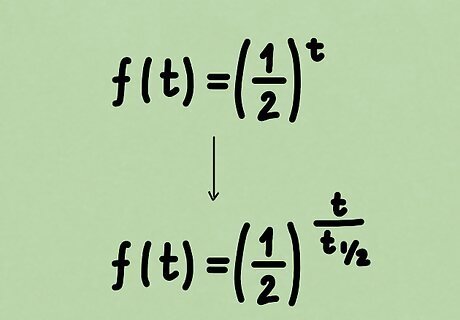

Rewrite the function in terms of half-life. Of course, our function does not depend on generic variable x , {\displaystyle x,} x, but time t . {\displaystyle t.} t. f ( t ) = ( 1 2 ) t {\displaystyle f(t)=\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{t}} f(t)=\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{{t}} Simply replacing the variable doesn't tell us everything, though. We still have to account for the actual half-life, which is, for our purposes, a constant. We could then add the half-life t 1 / 2 {\displaystyle t_{1/2}} t_{{1/2}} into the exponent, but we need to be careful about how we do this. Another property of exponential functions in physics is that the exponent must be dimensionless. Since we know that the amount of substance depends on time, we must then divide by the half-life, which is measured in units of time as well, to obtain a dimensionless quantity. Doing so also implies that t 1 / 2 {\displaystyle t_{1/2}} t_{{1/2}} and t {\displaystyle t} t be measured in the same units as well. As such, we obtain the function below. f ( t ) = ( 1 2 ) t t 1 / 2 {\displaystyle f(t)=\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{\frac {t}{t_{1/2}}}} f(t)=\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{{{\frac {t}{t_{{1/2}}}}}}

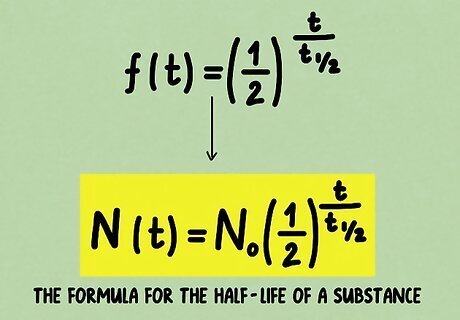

Incorporate the initial amount. Of course, our function f ( t ) {\displaystyle f(t)} f(t) as it stands is only a relative function that measures the amount of substance left after a given time as a percentage of the initial amount. All we need to do is to add the initial quantity N 0 . {\displaystyle N_{0}.} N_{{0}}. Now, we have the formula for the half-life of a substance. N ( t ) = N 0 ( 1 2 ) t t 1 / 2 {\displaystyle N(t)=N_{0}\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{\frac {t}{t_{1/2}}}} N(t)=N_{{0}}\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{{{\frac {t}{t_{{1/2}}}}}}

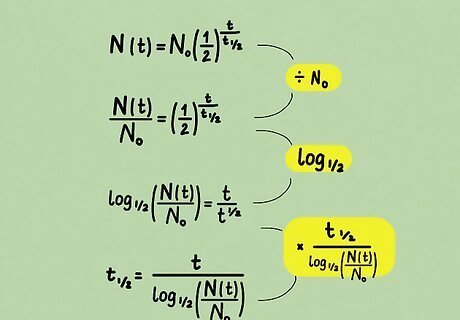

Solve for the half-life. In principle, the above formula describes all the variables we need. But suppose we encountered an unknown radioactive substance. It is easy to directly measure the mass before and after an elapsed time, but not its half-life. So, let's express half-life in terms of the other measured (known) variables. Nothing new is being expressed by doing this; rather, it is a matter of convenience. Below, we walk through the process one step at a time. Divide both sides by the initial amount N 0 . {\displaystyle N_{0}.} N_{{0}}. N ( t ) N 0 = ( 1 2 ) t t 1 / 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {N(t)}{N_{0}}}=\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{\frac {t}{t_{1/2}}}} {\frac {N(t)}{N_{{0}}}}=\left({\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{{{\frac {t}{t_{{1/2}}}}}} Take the logarithm, base 1 2 , {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}},} {\frac {1}{2}}, of both sides. This brings down the exponent. log 1 / 2 ( N ( t ) N 0 ) = t t 1 / 2 {\displaystyle \log _{1/2}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{0}}}\right)={\frac {t}{t_{1/2}}}} \log _{{1/2}}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{{0}}}}\right)={\frac {t}{t_{{1/2}}}} Multiply both sides by t 1 / 2 {\displaystyle t_{1/2}} t_{{1/2}} and divide both sides by the entire left side to solve for half-life. Since there are logarithms in the final expression, you'll probably need a calculator to solve half-life problems. t 1 / 2 = t log 1 / 2 ( N ( t ) N 0 ) {\displaystyle t_{1/2}={\frac {t}{\log _{1/2}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{0}}}\right)}}} t_{{1/2}}={\frac {t}{\log _{{1/2}}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{{0}}}}\right)}}

Calculating from a Graph

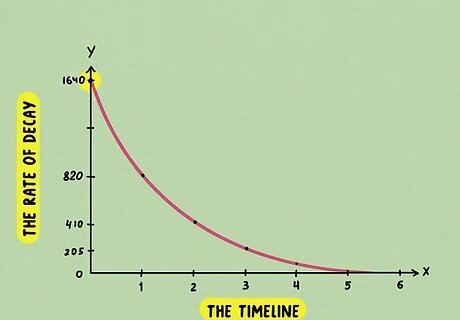

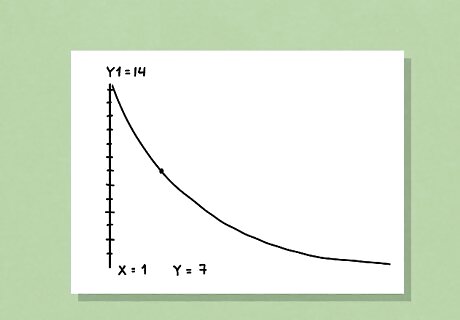

Read the original count rate at 0 days. Take a look at your graph and find the starting point, or the 0 day mark, on the x-axis. The 0 day mark is right before the material starts decaying, so it’s at its original point. On half-life graphs, the x-axis will usually show the timeline, while the y-axis usually shows the rate of decay.

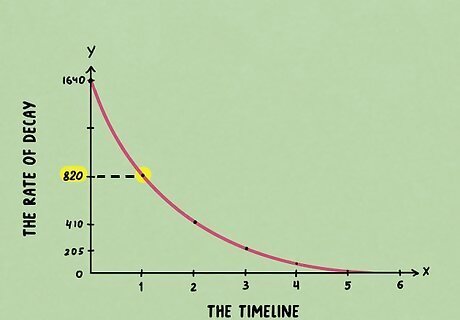

Go down half the original count rate and mark it on the graph. Starting from the top of the curve, note the count rate on the y-axis. Then, divide that number by 2 to get the number at the halfway point. Mark that point on the graph with a horizontal line. For example, if the starting point is 1,640, divide 1,640 / 2 to get 820. If you are working with a semi log plot, meaning the count rate is not evenly spaced, you’ll have to take the logarithm of any number from the vertical axis.

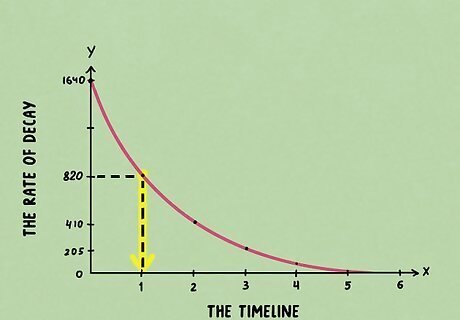

Draw a vertical line down from the curve. Starting from the halfway point that you just marked on the graph, draw a second line going downward until it touches the x-axis. Hopefully, the line will touch an easy-to-read number that you can identify.

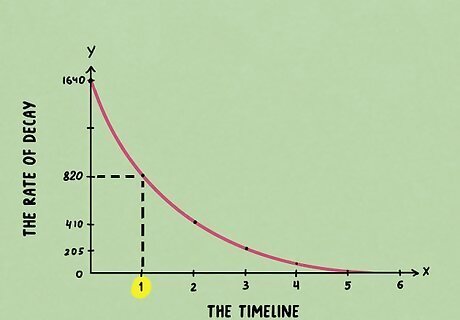

Read the half-life where the line crosses the time axis. Take a look at the point that your line touched and read where on the timeline it hits. Once you identify the point on your timeline, you’ve found your half-life.

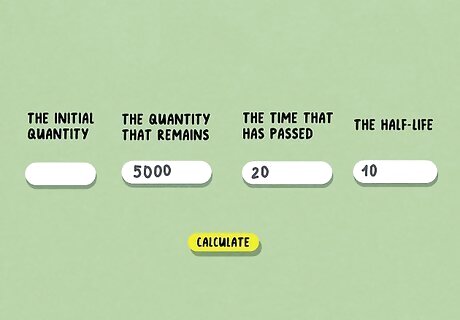

Using a Calculator

Determine 3 of the 4 relevant values. If you’re solving for half-life, you’ll need to know the initial quantity, the quantity that remains, and the time that has passed. Then, you can use any half-life calculator online to determine the half-life. If you know the half-life but you don’t know the initial quantity, you can input the half-life, the quantity that remains, and the time that has passed. As long as you know 3 of the 4 values, you’ll be able to use a half-life calculator.

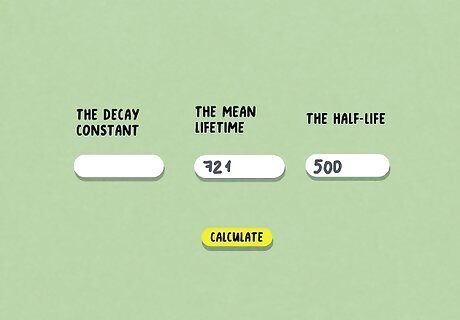

Calculate the decay constant with a half-life calculator. If you want to calculate how old an organism is, you can input the half-life and the mean lifetime to get the decay constant. This is a great tool to use for carbon dating or figuring out the lifespan of an organism. If you don’t know the half-life but you do know the decay constant and the mean lifetime, you can input those instead. Just like the initial equation, you only need to know 2 of the 3 values to get the third one.

Plot your half-life equation on a graphing calculator. If you know your half-life equation and you want to graph it, open up your Y-plots and input the equation into Y-1. Then, hit “graph” to open up your graph and adjust the window until you can see the whole curve. Finally, move your cursor above and below the midpoint of the graph to get your half-life. This is a helpful visual, and it can be useful if you don’t want to do all of the equation work.

Example Problems

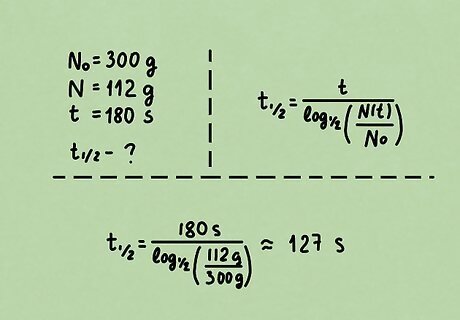

Problem 1. 300 g of an unknown radioactive substance decays to 112 g after 180 seconds. What is the half-life of this substance? Solution: we know the initial amount N 0 = 300 g , {\displaystyle N_{0}=300{\rm {\ g}},} N_{{0}}=300{{\rm {\ g}}}, final amount N = 112 g , {\displaystyle N=112{\rm {\ g}},} N=112{{\rm {\ g}}}, and elapsed time t = 180 s . {\displaystyle t=180{\rm {\ s}}.} t=180{{\rm {\ s}}}. Recall the half-life formula t 1 / 2 = t log 1 / 2 ( N ( t ) N 0 ) . {\displaystyle t_{1/2}={\frac {t}{\log _{1/2}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{0}}}\right)}}.} t_{{1/2}}={\frac {t}{\log _{{1/2}}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{{0}}}}\right)}}. Half-life is already isolated, so simply substitute the appropriate variables and evaluate. t 1 / 2 = 180 s log 1 / 2 ( 112 g 300 g ) ≈ 127 s {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}t_{1/2}&={\frac {180{\rm {\ s}}}{\log _{1/2}\left({\frac {112{\rm {\ g}}}{300{\rm {\ g}}}}\right)}}\\&\approx 127{\rm {\ s}}\end{aligned}}} {\begin{aligned}t_{{1/2}}&={\frac {180{{\rm {\ s}}}}{\log _{{1/2}}\left({\frac {112{{\rm {\ g}}}}{300{{\rm {\ g}}}}}\right)}}\\&\approx 127{{\rm {\ s}}}\end{aligned}} Check to see if the solution makes sense. Since 112 g is less than half of 300 g, at least one half-life must have elapsed. Our answer checks out.

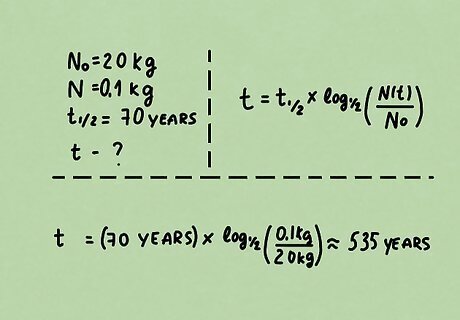

Problem 2. A nuclear reactor produces 20 kg of uranium-232. If the half-life of uranium-232 is about 70 years, how long will it take to decay to 0.1 kg? Solution: We know the initial amount N 0 = 20 k g , {\displaystyle N_{0}=20{\rm {\ kg}},} N_{{0}}=20{{\rm {\ kg}}}, final amount N = 0.1 k g , {\displaystyle N=0.1{\rm {\ kg}},} N=0.1{{\rm {\ kg}}}, and the half-life of uranium-232 t 1 / 2 = 70 y e a r s . {\displaystyle t_{1/2}=70{\rm {\ years}}.} t_{{1/2}}=70{{\rm {\ years}}}. Rewrite the half-life formula to solve for time. t = ( t 1 / 2 ) log 1 / 2 ( N ( t ) N 0 ) {\displaystyle t=(t_{1/2})\log _{1/2}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{0}}}\right)} t=(t_{{1/2}})\log _{{1/2}}\left({\frac {N(t)}{N_{{0}}}}\right) Substitute and evaluate. t = ( 70 y e a r s ) log 1 / 2 ( 0.1 k g 20 k g ) ≈ 535 y e a r s {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}t&=(70{\rm {\ years}})\log _{1/2}\left({\frac {0.1{\rm {\ kg}}}{20{\rm {\ kg}}}}\right)\\&\approx 535{\rm {\ years}}\end{aligned}}} {\begin{aligned}t&=(70{{\rm {\ years}}})\log _{{1/2}}\left({\frac {0.1{{\rm {\ kg}}}}{20{{\rm {\ kg}}}}}\right)\\&\approx 535{{\rm {\ years}}}\end{aligned}} Remember to check your solution intuitively to see if it makes sense.

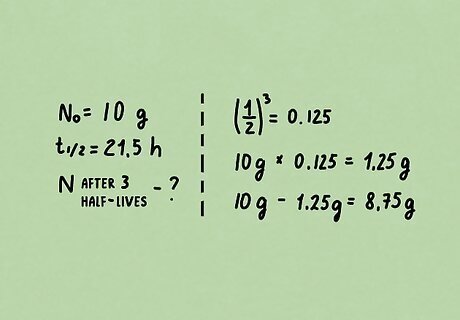

Problem 3. Os-182 has a half-life of 21.5 hours. How many grams of a 10.0 gram sample would have decayed after exactly 3 half-lives? Solution: ( 1 / 2 ) 3 = 0.125 {\displaystyle (1/2)^{3}=0.125} {\displaystyle (1/2)^{3}=0.125} (the amount remaining after 3 half-lives) 10.0 g x 0.125 = 1.25 g {\displaystyle 10.0gx0.125=1.25g} {\displaystyle 10.0gx0.125=1.25g} remain 10 g − 1.25 g = 8.75 g {\displaystyle 10g-1.25g=8.75g} {\displaystyle 10g-1.25g=8.75g} have decayed For this particular equation, the actual length of the half-life did not play a role.

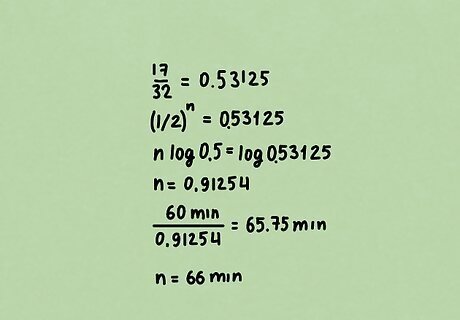

Problem 4. A radioactive isotope decayed to 17/32 of its original mass after 60 minutes. Find the half-life of this radioisotope. Solution: 17 / 32 = 0.53125 {\displaystyle 17/32=0.53125} {\displaystyle 17/32=0.53125} (this is the decimal amount that remains) ( 1 / 2 ) n = 0.53125 {\displaystyle (1/2)n=0.53125} {\displaystyle (1/2)n=0.53125} n l o g 0.5 = l o g 0.53125 {\displaystyle nlog0.5=log0.53125} {\displaystyle nlog0.5=log0.53125} n = 0.91254 {\displaystyle n=0.91254} {\displaystyle n=0.91254} (this is how many half-lives have elapsed) 60 m i n / 0.91254 = 65.75 m i n {\displaystyle 60min/0.91254=65.75min} {\displaystyle 60min/0.91254=65.75min} n = 66 m i n {\displaystyle n=66min} {\displaystyle n=66min} (to 2 sig figs)

Comments

0 comment