views

- Build your game from the top down by focusing on the plot and pacing first, and the minor details at the end.

- Use whatever medium you enjoy to build your ARG. There are no rules, so you can write, film, record, or create whatever you’d like.

- You can have as much story and narrative as you’d like. Some ARGs, like geocaching or Pokémon Go have no plot at all!

- ARGs are often very light on the “game” component. So long as your players are intrigued, you’re doing your job as the writer.

Familiarize yourself with what makes ARGs unique.

ARGs have unique layers that make them fascinating to build. Wondering what an ARG is? An alternate reality game (ARG), also known as an unfiction, refers to an interactive narrative that relies on the real-world player experience as the primary setting for events. Basically, picture a game that takes place in the real world. ARGs often employ multiple forms of media, like written text, websites, objects, video, or more to immerse players in a story or experience unlike traditional games or works of literature. Escape rooms, murder mysteries, and IRL treasure hunts are super simple examples of an alternate reality game. However, most ARGs tend to be a little more complex and mysterious. Junko Junsui is a famous example of an ARG. After watching a strange video, players must go to “174.133.240.117,” find “the enemy” and add a series of fake Facebook accounts to solve a cryptic mystery and defeat a fictional cult.

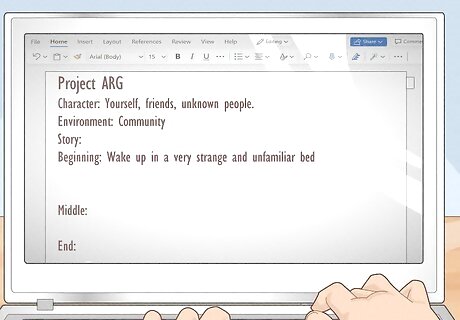

Sketch out the plot.

Start by figuring out what the story is going to be. You don’t need to write a novel if you don’t want to, but at least outline the beginning, middle, and end. What is the conflict? Why are the players called into action? Where does the story take place? It’s okay if the answer to all these questions is simple, but the core story should drive each writing decision and gameplay design choices. Your game doesn’t need a crazy complicated plot to be interesting. Geocaching is an ARG, and it’s got no plot whatsoever! For example, your plot could be about a secret organization trying to vet potential detectives by having them solve increasingly complex problems. You can also have a branching narrative where the player’s decisions or success/failure can change the story.

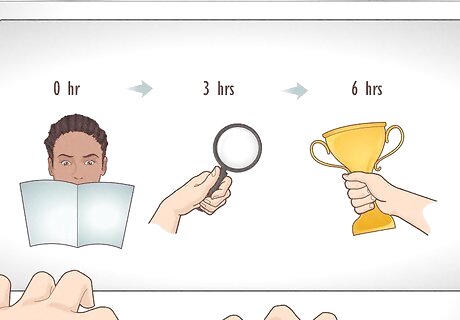

Keep the timeline in mind.

ARGs take place in real-time, so pace your story accordingly. You can’t hit the pause button on reality, so keep a mental model on how long your ARG will take players. Cicada 3301, the famous cipher and puzzle game, famously took its players 3 years to complete! You’re unlikely to keep a player’s attention for that long, so try to keep it under 6-10 hours if possible. Some ARGs don’t have time limits—it’s up to the user to determine when the story stops and starts. The video game Pokémon Go is a popular example. Many ARGS are played as archeological projects—every game element is present from the beginning and it’s the player’s job to solve or reassemble each piece. If you’re going to go for a nonlinear narrative, take the complexity of each task into account when you monitor the timeline.

Craft a riveting hook for the game.

Every ARG needs a trigger to send the player down the rabbit hole. You might invite players to begin playing by sharing a creepy paragraph that links to an app, crafting a QR code that links to a mysterious website, or setting up posters that provide instructions on how to play. Keep it intriguing, but provide enough context for the story to give players the info they need. Good examples of a precursor for an ARG might be: “They are communicating to us through the radio. Download the app and find the right frequency. More instructions will follow. We can fight them together.” “All around you are hidden messages. Signs that we are being invaded by body snatchers who look just like you or me are everywhere. Will you stand up for humanity?” Players are presented with a strange image of an octopus pointing at a stop sign in your city. If players go to that exact stop sign, they’ll find an ad seeking out underwater explorers with “take one” tabs containing a URL to the puzzle.

Select your mediums.

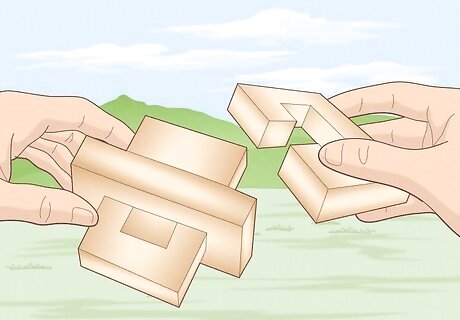

Choose what materials you’ll work in based on your skills and interests. You can create an ARG out of literally anything, so pick mediums that you find interesting to work with. You could create an ARG that’s entirely text-based, or use illustrations to tell the story without so much as a single line of instructions. The most popular options include: Building a website. Create a simple web page to share narrative bits, puzzles, or clues. Recording audio files. You might encrypt audio files with clues and puzzles, or use found snippets to tell a story. Making IRL objects. You could hide origami objects as clues, or make fake artifacts from a lost civilization for players to find. Writing false documents. False documents are a big part of many ARGs; they refer to letters, bank statements, legal documents, and other written materials that come from fictional characters.

Determine how the player collaborates.

Every ARG requires player engagement, so what will your player do? No ARG exists without a player participating in the narrative. Are your players going to solve word puzzles? Find clues? Translate morse code? Keep your players active and engaged by giving them choices to make in the game through the gameplay. If your story revolves around defeating an otherworldly demon, your player might need to find runes in an area and then place them in the right pattern to save the world. In this example, players are creating the story with you by either locating what they need and solving the puzzles, or failing and letting humanity collapse! While some ARGs are designed to be single-player experiences, most are meant to be played socially if the player so chooses. They might collaborate together on puzzles or share evidence they find. For example, The Backrooms is a popular narrative ARG about a hidden world people can “clip” into on accident. Players roleplay online by sharing new discoveries and pretending to be trapped there.

Keep things simple.

The open nature of ARGs makes complex tasks hard for players. It’s okay to craft complex puzzles that require some critical thinking, but the gameplay elements themselves shouldn’t be hard to parse or understand. In other words, don’t nest a puzzle inside of a clue that refers to another puzzle. Give players one task at a time and try to make your tasks intuitive. When you’re testing the game, ask your younger brother or sister to try it first if you have any siblings. They’ll give you a good sense for whether your game is too complicated. Since you aren’t going to be standing next to the player to answer questions or provide hints, you can’t help them if they get stuck. For example, you could have players to solve a puzzle where they have to solve complex equations to discover a passcode that they enter into a website to access secret files.

Develop any characters.

If you have any NPCs, use them to build tone or move the plot. NPCs may appear in videos, photos, or in written form. Since players can’t interact directly with NPCs (unless your ARG is a video game), you’ll get the most impact out of the characters you develop by making them vivid to enforce the tone of your work or to give players tasks, hints, or instructions to keep the game going. For example, if you’ve got a cyberpunk thing going on in your game, you might solicit friends to dress up for photos or videos and incorporate those in your game. Your ARG might have a villain. If it does, what do they want? Why are they in conflict with the player? ARGs rarely have traditional player characters. The player in each game is typically the biographical player.

Link the gameplay to the story.

Keep players involved by lining up player behavior with the theme. As you’re building your game, try to ensure that whatever the player is doing makes sense for the core message of the story. If the player’s tasks don’t make sense in the context of the story, they’ll lose interest. For example, if your players are fighting a pandemic virus, you might have their puzzles become increasingly confused or hard to solve as the player gets sicker and sicker. This is why escape rooms are such popular ARGs; the time limit combined with the fact that you’re locked in somewhere contribute to the feeling like you’re trapped! When gameplay and the theme of the story don’t line up, it creates ludonarrative dissonance—a feeling of being “lost” or “off” when mechanics don’t make sense. A good example of this is Michael in Grand Theft Auto 5. His character is supposed to be trying to reform himself as a family man, but he spends every mission killing people.

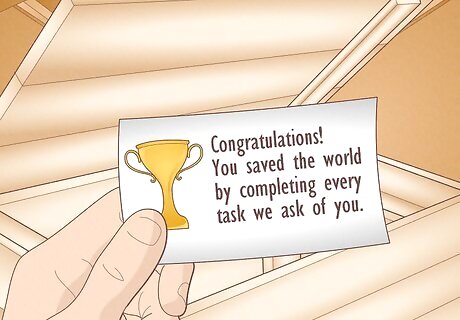

Include a win-state.

How will the player know they’ve won or lost? You might award the player with a paragraph of text explaining they’ve saved the world, rescued the president’s daughter, or whatever your story is about. Alternatively, you might give the player a physical token to demonstrate they’ve completed the game. In many ARGs, the loss state is simply not knowing what happens at the end of the story. It is totally okay to have no win or loss state if your ARG isn’t time-bound or the loop can be repeated infinitely. To go back to narrative resonance and gameplay for a second, if your game is mainly narrative, the win state should be narrative. If the game is about puzzles, the final task should be a super compelling puzzle.

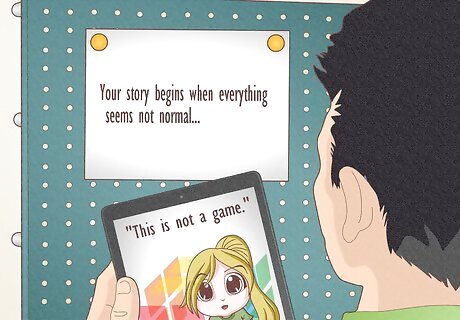

Aim to make your game not game-like.

Put your worldbuilding and storytelling first. There’s a popular acronym among ARG designers (also known as puppet masters), TINAG. It stands for “this is not a game.” Basically, remember that you aren’t making a video game or board game. The goal is to give your players a unique experience they won’t forget, so don’t try to gameify everything. In other words, if you’ve got a great idea for a plot point and you don’t know how to convert it into a player task, don’t even try! Give the player the material in written, video, or digital form and then move on. They don’t always have to be doing something. Many ARGs do not feel like games to players. They feel more like community storytelling or experiments with a puzzle element. Murder, for example, is basically just a choose-your-own-adventure story that involves you doing a few things at home.

Comments

0 comment