views

- Make character sheets and choose a story setting. Then, create a plot outline to guide you through the story-writing process.

- Set the scene, introduce the characters, and establish a problem for the characters to solve in the first 2-3 paragraphs.

- Fill the middle of the story with action that shows the character(s) working on the problem. Present 2-3 new challenges to keep things interesting.

- Create dialogue that reveals something about your characters and keeps readers' eyes move down the page.

Developing Characters and Plot

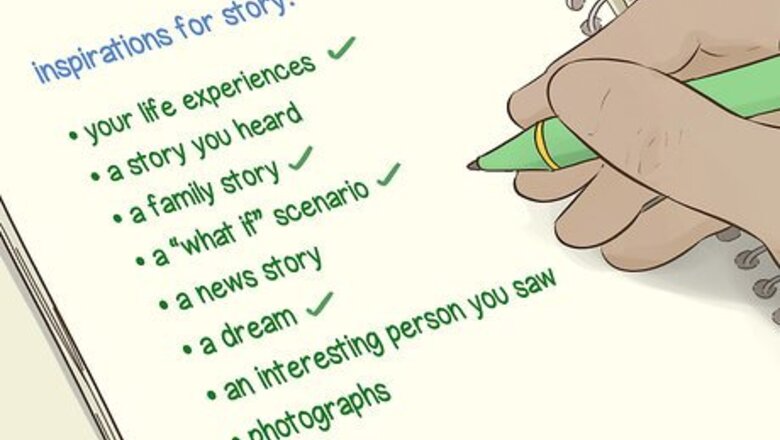

Brainstorm to find an interesting character or plot. The spark for your story might come from a character you think would be interesting, an interesting place, or a concept for a plot. Write down your thoughts or make a mind map to help you generate ideas. Then, pick one to develop into a story. Here are some inspirations you might use for a story: Your life experiences A story you heard A family story A “what if” scenario A news story A dream An interesting person you saw Photographs Art

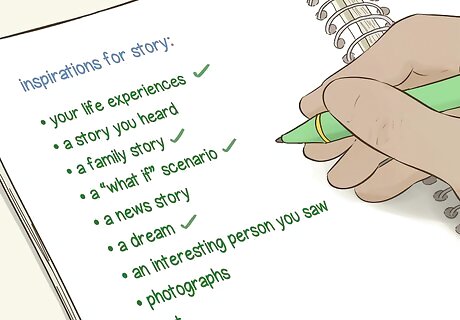

Develop your characters by making character sheets. Characters are the most essential element of your story. Your reader should relate to your characters, and your characters should be driving your story. Make profiles for your characters by writing their name, personal details, description, traits, habits, desires, and most interesting quirks. Provide as much detail as you can. Do the sheet for your protagonist first. Then, make character sheets for your other main characters, like the antagonist. Characters are considered main characters if they play a major role in the story, such as influencing your main character or affecting the plot. Figure out what your characters want or what their motivation is. Then, base your plot around your character either getting what they want or being denied it. You can create your own character sheets or find templates online.

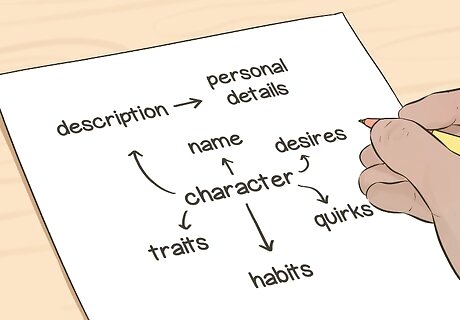

Choose a setting for your story. The setting is when and where your story takes place. Your setting should influence your story in some way, so pick a setting that adds to your plot. Consider how this setting would impact your characters and their relationships. For example, a story about a girl who wants to become a doctor would go much differently if it were told in the 1920s instead of 2019. The character would need to overcome additional obstacles, like sexism, due to the setting. However, you might use this setting if your theme is perseverance because it allows you to show your character pursuing her dreams against societal norms. As another example, setting a story about camping deep in an unfamiliar forest will create a different mood than putting it in the main character's backyard. The forest setting might focus on the character surviving in nature, while the backyard setting may focus on the character's family relationships.Warning: When you pick your setting, be careful about choosing a time period or place that's unfamiliar to you. It's easy to get details wrong, and your reader may catch your errors.

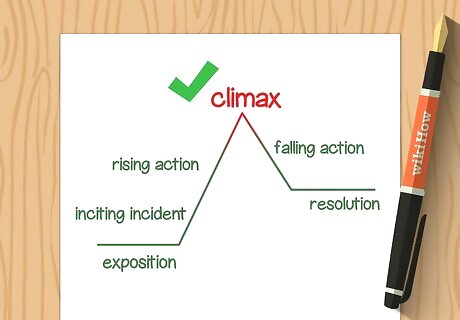

Create an outline for your plot. Making a plot outline will help you know what to write next. Additionally, it helps you fill in any plot holes before you begin. Use your brainstorming exercise and character sheets to plot out your story. Here are some ways you can make your outline: Create a plot diagram consisting of an exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. Make a traditional outline with the main points being individual scenes. Summarize each plot and turn it into a bullet list.

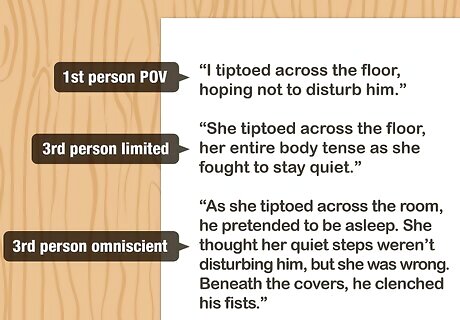

Choose a first person or third person point-of-view (POV). POV can change the entire perspective of the story, so choose wisely. Choose 1st person POV to get really close to the story. Use 3rd person limited POV if you want to focus on one character but want enough distance from the story to add your own interpretations to events. As another option, pick 3rd person omniscient if you want to share everything that’s happening in the story. 1st person POV - A single character tells the story from their perspective. Because the story is the truth according to this one character, their account of events could be unreliable. For instance, “I tiptoed across the floor, hoping not to disturb him.” 3rd person limited - A narrator recounts the events of the story but limits the perspective to one character. When using this POV, you can’t provide the thoughts or feelings of other characters, but you can add your interpretation of the setting or events. For example, “She tiptoed across the floor, her entire body tense as she fought to stay quiet.” 3rd person omniscient - An all-seeing narrator tells everything that happens in the story, including the thoughts and actions of each character. As an example, “As she tiptoed across the room, he pretended to be asleep. She thought her quiet steps weren’t disturbing him, but she was wrong. Beneath the covers, he clenched his fists.”

Drafting Your Story

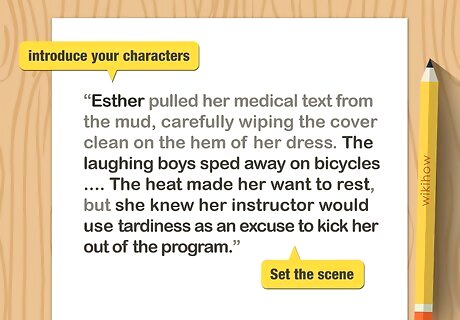

Set the scene and introduce your characters in the beginning. Spend the first 2-3 paragraphs immersing your reader in the setting. First, place your character in the setting. Then, give a basic description of the place, and incorporate details to show the era. Give just enough information for your reader to paint a picture in their mind. You might start your story like this: “Esther pulled her medical text from the mud, carefully wiping the cover clean on the hem of her dress. The laughing boys sped away on bicycles, leaving her to walk the last mile to the hospital alone. The sun beat down on the rain-soaked landscape, turning the morning’s puddles into a dank afternoon haze. The heat made her want to rest, but she knew her instructor would use tardiness as an excuse to kick her out of the program.”

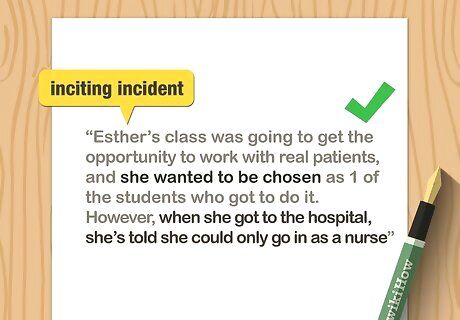

Introduce a problem in the first few paragraphs. Your problem will act as an inciting incident that triggers your plot and keeps your character reading. Think about what your character wants, and why they can’t have it. Then, create a scene that shows them encountering this problem. For example, let’s say that Esther’s class is going to get the opportunity to work with real patients, and she wants to be chosen as 1 of the students who gets to do it. However, when she gets to the hospital, she’s told she can only go in as a nurse. This sets up a plot where Esther tries to earn her spot as a doctor-in-training.

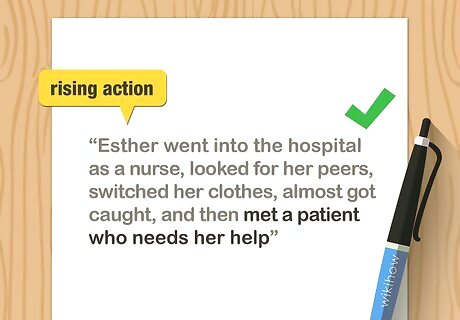

Fill the middle of your story with rising action. Show your character working on their problem. To make your story more interesting, incorporate 2-3 challenges they face as they move toward the climax of your story. This builds the reader’s suspense before you reveal what happens. For example, Esther might go into the hospital as a nurse, look for her peers, switch her clothes, almost get caught, and then meet a patient who needs her help.

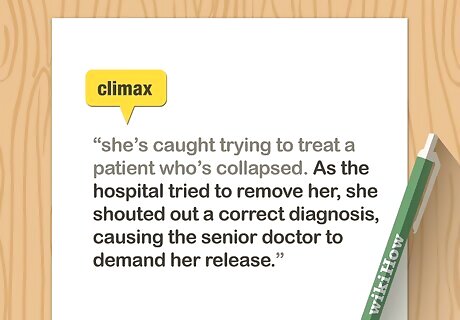

Provide a climax that resolves the problem. The climax is the peak of your story. Create an event that forces your character to fight for what they want. Then, show your character either winning or losing. In Esther's story, the climax might occur when she’s caught trying to treat a patient who’s collapsed. As the hospital tries to remove her, she shouts out a correct diagnosis, causing the senior doctor to demand her release.

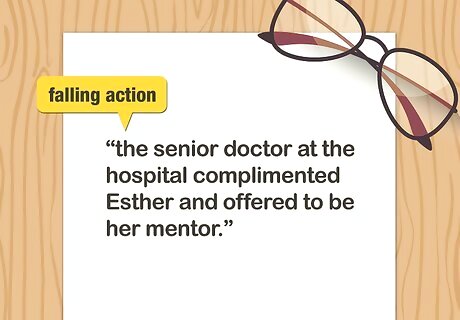

Use falling action to move the reader toward your conclusion. Keep your falling action brief because your reader won’t be as motivated to keep reading after the climax. Use the final couple of paragraphs to wrap up the plot and summarize what happened after the resolution of the problem. For instance, the senior doctor at the hospital might compliment Esther and offer to be her mentor.

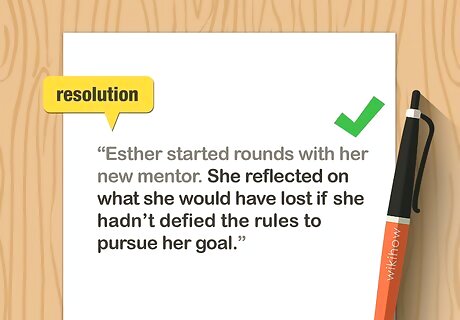

Write an ending that gives the reader something to think about. In your first draft, don’t worry about making your ending good. Instead, focus on presenting your theme and suggesting what your character might do next. This will leave the reader thinking about the story. Esther’s story might end with her starting rounds with her new mentor. She might reflect on what she would have lost if she hadn’t defied the rules to pursue her goal. Malcolm Gladwell Malcolm Gladwell, Writer Your words should have an impact. "Good writing does not succeed or fail on the strength of its ability to persuade. It succeeds or fails on the strength of its ability to engage you, to make you think, to give you a glimpse into someone else's head."

Improving Your Story

Begin your story as close to the end as you can. Your reader doesn’t need to read about every event that leads to the problem your character is dealing with. They only want to see a snapshot of your character’s life. Pick an inciting incident that gets the reader into the plot quickly. This will help you ensure your story doesn’t move too slowly. For example, starting with Esther walking to the hospital is a better place to start than when she enrolled in medical school. However, it might be even better to start when she arrives at the hospital.

Incorporate dialogue that reveals something about your characters. Dialogue breaks up your paragraphs, which helps your reader’s eyes move down the page. Additionally, dialogue lets you present what your characters are thinking in their own words without having to include a lot of internal monologue. Use dialogue throughout your story to convey your character’s thoughts. However, make sure each piece of dialogue is driving the plot. For example, this piece of dialogue shows us that Esther is frustrated: “But I’m the top student in my class,” Esther pleaded. “Why should they get to examine patients but not me?”

Build tension by having bad things happen to your characters. It’s hard to do mean things to your characters, but your story will be boring if you don’t. Give your characters obstacles or hardships that keep them away from what they want. That way, you’ll have something to resolve in order for them to reach their desires. For example, Esther being denied entry to the hospital as a doctor is a horrible experience for her. Similarly, being grabbed by security would be frightening.

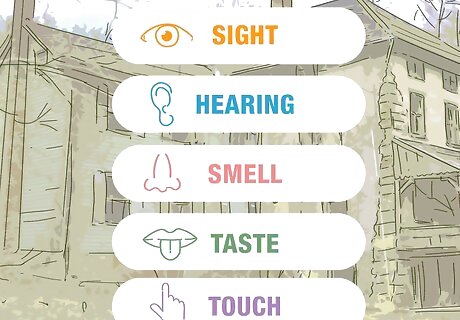

Stimulate the 5 senses by including sensual details. Use the senses of sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste to bring your reader into the story. Make your setting more dynamic by showing your reader what sounds they would hear, the smells they would notice, and the sensations they’d feel. This will make your story more engaging. For example, Esther could react to the smell of the hospital or the sound of beeping machines.

Use emotion to help the reader relate to your story. Try to make your readers feel what your character is feeling. Do this by connecting what your character is going through to something universal. The emotions will draw readers into your story. For instance, Esther has worked really hard for something only to be denied it based on a technicality. Most people have experienced a failure like this before.

Revising and Finalizing the Story

Set your story aside for at least a day before revising it. It’s difficult to revise your story right away because you won’t be able to notice your errors and plot holes yet. Leave it alone for a day or longer so that you can look at it with fresh eyes. Printing out your story may help you see it from a different perspective, so you might try that when you go back to revise it. Setting your work aside for a little while is a good move, but don't set it aside for so long that you lose interest in it.

Read your story aloud to listen for areas that need improvement. When you read your story aloud, you get a different perspective on it. This will help you identify passages that don’t flow well or sentences that sound choppy. Read your story to yourself and make notes where you need to revise it. You can also read your story to other people and ask them for advice.

Get feedback from other writers or people who read often. When you’re ready, show your story to a fellow writer, instructor, classmate, or friend. If you can, take it to a writing critique or workshop. Ask your readers to provide their honest feedback so you can improve your story. The people closest to you, like your parents or best friend, may not provide the best feedback because they care about your feelings too much. However, you may be able to find a writing critique group on Meetup.com or at your local library. For feedback to be helpful, you have to be receptive to it. If you think you've written the most perfect story in the world, then you won't actually hear a word anyone says. Make sure you're giving your story to the right readers. If you're writing science fiction but have handed your story to your writer friend who enjoys literary fiction, you may not get the best feedback. EXPERT TIP Lucy V. Hay Lucy V. Hay Professional Writer Lucy V. Hay is a Professional Writer based in London, England. With over 20 years of industry experience, Lucy is an author, script editor, and award-winning blogger who helps other writers through writing workshops, courses, and her blog Bang2Write. Lucy is the producer of two British thrillers, and Bang2Write has appeared in the Top 100 round-ups for Writer’s Digest & The Write Life and is a UK Blog Awards Finalist and Feedspot’s #1 Screenwriting blog in the UK. She received a B.A. in Scriptwriting for Film & Television from Bournemouth University. Lucy V. Hay Lucy V. Hay Professional Writer If you're getting good feedback, consider submitting your story to a short story contest. Some short story contests have prizes, like being published in an anthology or having a chance meet an agent. Those types of things can be valuable to you later on. For instance, if you get published in several anthologies, you can utilize that when you're making submissions to agents. Some competitions, like the Bridport Prize and the Bath Short Story Award in the UK, are very prestigious—if you can win one of those, you'll actually be seen as a writer with some significant chops.

Eliminate anything that doesn’t reveal character details or advance the plot. This may mean cutting passages that you think are well-written. However, your reader is only interested in details that are important for the story. As you revise your work, make sure every sentence you save shows something about your character or pushes the plot forward. Cut any sentence that doesn’t. For instance, let’s say there’s a passage where Esther sees a girl in the hospital who reminds her of her sister. While this detail might seem interesting, it doesn’t advance the plot or show something meaningful about Esther, so it’s best to cut it.

Comments

0 comment