views

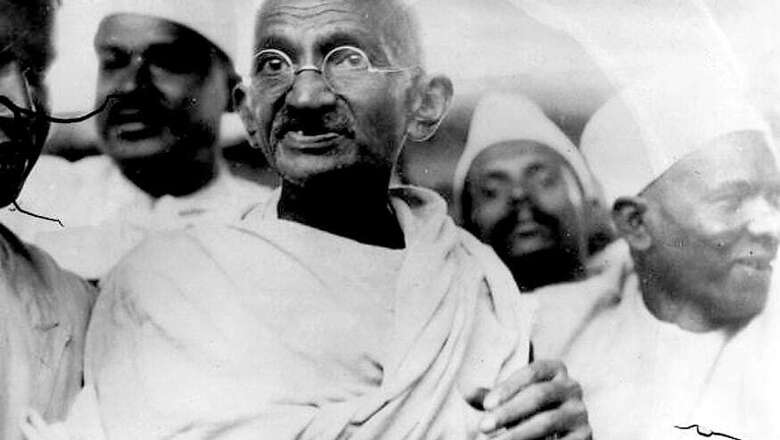

If politics is about symbols and percepts, then Mahatma Gandhi was perhaps its finest connoisseur. The movements he presided over, the milk that he consumed, the charkha that he spun, his clothing, his sandals or just about everything around him had a distinct Gandhi insignia — a colophon of sorts.

Not that Gandhi gave a call for political mobilisation every other day. In fact, just three in his entire career at the helm of Indian Freedom Movement. But in all three instances, he knew precisely the intended objective of a protest and the exit route when the purpose was achieved.

But what set him apart among all his contemporaries, or even among those who followed him, was Gandhi’s sense of aesthetics in political mobilisation. The de rigueur of a Mahatma, up against the might of the British government.

‘World’s Last Englishman’, Nirad Chaudhuri in his memoirs gives a rare glimpse of the rigours involved in procuring goat milk during Gandhi’s visit to the Bose household in Kolkata.

Chaudhuri was then working as personal secretary to Subhash Chandra Bose’s elder brother Sarat Chandra. The elaborate exercise involved Gandhi’s formidable secretary Mahadev Desai choosing from a herd of goats which one would have the “privilege of serving as the foster-mother”.

Chaudhuri took goats for goats, wherein the entire ritual was about cows- underscoring Gandhi’s Hindu credentials. Both in form and content, Gandhi carefully chose to be more Hindu than a typical Hindu nationalist. He understood his people and their oracles, their articles of faith. And he seamlessly assimilated them in his discourse as a thoroughbred politician would do.

Gandhi’s symbolism rubbed on friends and foes alike. His staunchest critic and fellow barrister Mohammad Ali Jinnah in his avatar as the proponent of the two-nation theory had to make some sardonic adjustments — from three-piece suit to sherwani and Aligarhi pajama. Jinnah called Gandhi a Hindu agent and Congress a party espousing the majoritarian cause. By default, Gandhi and Congress were the choice of the overwhelming majority.

Gandhi preached what he practised. Cleaning toilets for him was part of the larger sanitation drive. But it also had political undertones with a powerful message to the ‘untouchables’. So despite having convoluted and complex views on caste system, Gandhi could still confront the tallest Dalit leader at that time, Dr. BR Ambedkar and tire him out to sign the Poona Pact.

Leaders rooted strongly in their core constituency are more apt at managing contradictions. Vajpayee, before Modi leading a Right-wing government, it is said, was better placed to seek stable solution on Kashmir. Similarly, Gandhi could forcefully espouse a secular because he had high Hindu credentials. Gandhi’s visibly Hindu mien gave him manoeuvring space like no one else.

His pilgrimage to Noakhali in the face of communal carnage and his views on the division of assets between India and Pakistan irked many. But the allegations could never really stick. Not even in the surcharged atmosphere of partition and thereafter.

Politically one could never really beat Gandhi. So, he had to be eliminated, physically.

Comments

0 comment