views

The Global Nutrition Report tracks progress on six global nutrition targets identified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and aims to be achieved by 2025. In 2021, it noted that India is ‘on course’ to meet three of these targets – those for maternal, infant and young child nutrition. However, it also observed that 34.7 percent of children under five years of age continue to be affected with stunting. This rate is higher than the average for the Asia region. In addition, it reported that “India has made no progress towards achieving the target for wasting, with 17.3 percent of children under five years of age affected, which is higher than the average for the Asia region (8.9 percent) and among the highest in the world.”

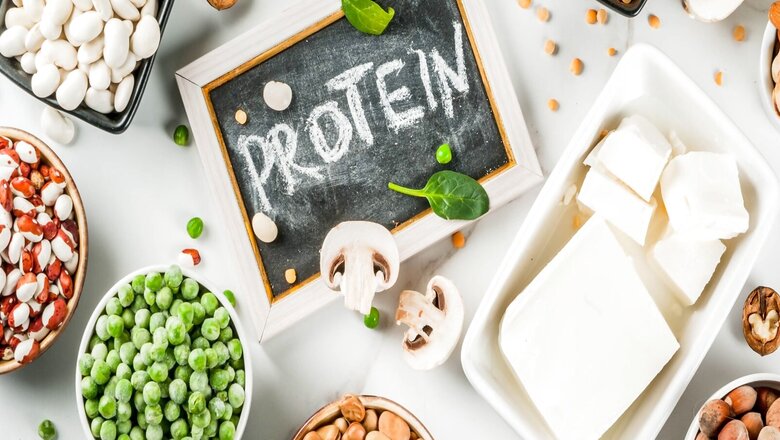

Protein malnutrition can be an underlying cause of both stunting and wasting. Indeed, surveys have demonstrated that the majority of Indians lack both awareness of protein in Indian diets and consumption of adequate amounts of protein. This likely translates into low inclusion of protein in diets at critical stages – during pregnancy and lactation for the mother and growth stages for infants and young children. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) recommends protein intake of ~1gm/kg/day for adults, ~1.5gm/kg/day for pregnant women and ~1.5gm/kg/day for infants and young children. However, the average daily intake is about 0.6 gm per kg body weight.

Back in the 1960s, the presence of a ‘protein gap or crisis’ in the diets of developing world economies was noted. The United Nations (UN) constituted an ‘International Action to Avert the Impending Protein Crisis’ with seven policy objectives. The programme also suggested recommendations to address the protein gap – these included adding essential amino acids to ordinary plant proteins and formulating food mixes with essential amino acid content for supplementation of diets. In its ‘Strategy Statement on Action to Avert the Protein Crisis in Developing Countries’, the UN observed that protein malnutrition is an important cause of infant and young child mortality, stunted physical growth, low work output, premature ageing and reduced life span in the developing world. However, the focus on protein malnutrition, in the context of larger food security challenges, was eventually challenged. This led to reduced attention and funding for protein malnutrition in the later years.

However, seminal work in the mid-1990s rejuvenated interest in protein malnutrition with studies attributing over 50 percent of child deaths in developing countries to protein malnutrition. There is an increasing emphasis on including protein and particularly essential amino acids in diets. In this context, access to good quality protein becomes an important lever for achieving a balanced diet for India’s population.

There are cultural barriers to including more protein in Indian diets, which are predominantly cereal-based. Though cereals contain proteins, these have poor digestibility and quality. The Indian consumer market 2020 showed that Indians have a high monthly expenditure on cereals and processed foods. However, we spend only one-third of the food budget on protein-rich foods. Access to high-protein non-vegetarian food is an issue because of its associated high cost and the low-cost vegetarian options disseminated through the public distribution system (PDS) are poor in protein provisions. There has also been resistance to providing eggs and other non-vegetarian protein sources by partners of the government-sponsored mid-day meal programmes.

These challenges highlight the need for innovation in policy governing the inclusion of protein in Indian diets. The first policy intervention has to centre around awareness of protein sources in the diet. These should include both vegetarian (for example soy) and non-vegetarian protein sources. The importance of protein intake, particularly for pregnant and lactating women and growing children, needs to be emphasised. Protein deficiency in adults may lead to weakness and delays in wound healing and, in the long term, can drive lifestyle diseases such as diabetes. The lack of appropriate protein intake puts children at risk of poor brain development, low immunity, and increased infections. Poor nutrition for a pregnant mother and infant can have inter-generational impacts, hampering proper growth for future children as well. These risks have to be communicated to families so that they can prioritise nutrition and protein intake in their diet.

The second policy intervention is to enable access to protein – this can include more protein sources in the PDS system, facilitating supply of more protein-rich products and researching safe meat protein substitutes for those who may not be eating meat protein. The mid-day meal programme, in particular, should include protein sources – both vegetarian and non-vegetarian – as this is a critical age group to target. Similarly, schemes targeting pregnant women and lactating mothers should include appropriate protein sources.

As we marked Protein Day on February 27, it is important to remember that essential amino acids are critical to human development. The health and productivity of our future generations hinge on their proper growth. Hence, it is important to enable access to good quality protein as part of everyone’s balanced diet.

Shambhavi Naik is Head of Research at the Takshashila Institution, Bengaluru. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment