views

Major trade supply chains stand disrupted by ongoing conflicts around the world. The economies of developing states, in particular, have been hit hard with unabated increases in the cost of basic commodities and the associated cost of living. Turmoil and uncertainty best describe today’s situation as the world transitions from a unipolar to a multipolar order.

As we navigate this evolving world order, the term “strategic autonomy” resonates even more strongly. This concept involves a state adopting a neutral or intentionally ambiguous stance within the global order, transacting in global trade solely in the best interest of its own constituents. Yet, even this approach is proving tenuous, especially for smaller developing economies facing the threat of economic sanctions imposed by larger powers.

The ASEAN Development Outlook reports that ASEAN, a regional grouping of 10 Southeast Asian nations, boasts a combined GDP of $3.6 trillion, effectively making it the fifth-largest economy in the world. This economic powerhouse is projected to become the fourth-largest by 2030. ASEAN offers a wealth of raw commodities and a vast talent pool of nearly 700 million people. Geographically strategic, its member states straddle two of the world’s most significant trade routes: the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

To the east lies the South China Sea, a 3-million-square-kilometre body of water bordered by several ASEAN states, China, and Taiwan. This vital shipping route, carrying trillions of dollars in cargo, serves as a gateway to the Indian Ocean. Moreover, the South China Sea is rich in oil and gas deposits and boasts thriving marine life, providing a crucial food source for the burgeoning East Asian population. China undeniably dominates the Asia-Pacific economic sphere through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest trading bloc. Established in 2022 as an economic alternative to the US-led Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), RCEP encompasses 15 Asia-Pacific countries. China is ASEAN’s largest trading partner by far, with over $447.3 billion in two-way trade.

And on the western front, several ASEAN states border the Indian Ocean. This body of water stretches from Africa’s east coast to Australia’s western coast and is home to 33 nations and over 36 per cent of the total global population, totalling 2.9 billion people. Annual trade across this region stands at over $6.17 trillion (in 2020, and this figure could well be over $7 trillion in 2023 – Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), with over 80 per cent of the world’s maritime oil and close to 10 billion metric tons of cargo ranging from food and precious metals to manufactured goods. The Indian Ocean region is also critical for the global movement of liquid energy, with about 65 per cent of the world’s oil reserves belonging to ten of the Indian Ocean’s littoral states. Unmistakably, this region handles close to half of the global trade, which amounts to around $14 trillion.

While ASEAN is located on the cusp of these two colossal trade routes, it also forms a central part of the Asian economic community. Although not currently a formal economic trading bloc, the Asian GDP stands at $42.7 trillion (according to the International Monetary Fund), which represents a significant trade opportunity that should not be underestimated.

Furthermore, Malaysia and Thailand’s individual expressions of interest in joining the rapidly expanding BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) add another layer of trade possibilities. BRICS, originally formed as an alternative economic alliance in 2006 and further formalised in 2010 with the entry of South Africa, recently announced the participation of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. The potential collaboration or formal entry of ASEAN as a comprehensive economic bloc into this fast-expanding grouping would certainly enhance trade and security opportunities.

While Malaysia continues to be a close trading partner with the US and European Union, it must also maintain its strategic trade relationship with China, given that a significant portion of Malaysia’s base commodities, such as food products and other essential goods, are primarily sourced from there. As a result, Malaysia faces a trade deficit of over $22.8 billion with China.

However, Malaysia is uniquely positioned on both the Indian Oceanic route and the South China Sea. The country clearly needs a balanced foreign and trade policy that leverages other strategic neighbours. For instance, India, with its geographic proximity to Malaysia, is a prime partner that could be further leveraged. The existing trade balance of $4.77 billion in Malaysia’s favour highlights this potential. As the second-largest food-producing country, India offers Malaysia added opportunities for food security and other technological advancements.

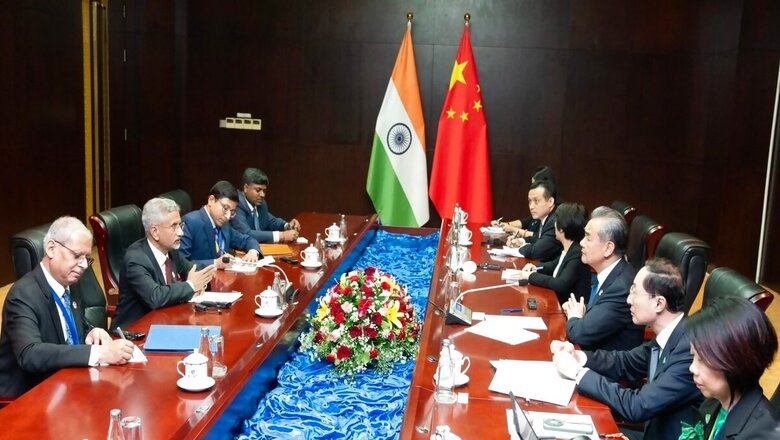

Furthermore, in this current geopolitical and geo-economic environment, India and China are in the midst of redefining their trade and security relationship. As asserted by the Vice Chairman of NITI Aayog, “It is not easy to cut the Indian economy off from that of the Chinese economy. There needs to be more clarity to India’s relationship with China as it remains an important trading partner for India.”

This may offer Malaysia an interesting opportunity to help bridge this partnership. Malaysia holds unique geopolitical significance for both India and China as major economies. It has civilisational linkages to both countries that date back many centuries, in addition to current people-to-people relationships among its diaspora with ancestral ties to these nations. In addition, it has a one-of-a-kind strategic positioning, both on the Straits of Malacca, which is the entry point to the Indian Ocean Trade Route, and directly on the South China Sea. Furthermore, Malaysia also forms part of the trans-Asia rail network.

As ASEAN Chair in 2025, Malaysia has a unique opportunity to strengthen trade and supply chain security within the region. Moreover, Malaysia could adopt a more strategic role in fostering partnerships between ASEAN and emerging economic blocs like BRICS, contributing to a more balanced and secure trading environment in the Indo-Pacific.

The question is: while acknowledging and reasserting its strategic geopolitical positioning, could Malaysia become the fulcrum that helps craft an ASEAN-India-China relationship, reaching greater heights in 2025 and beyond?

The author is Senior Correspondent on Foreign Policy and Politics, Malaysia Gazette. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment