views

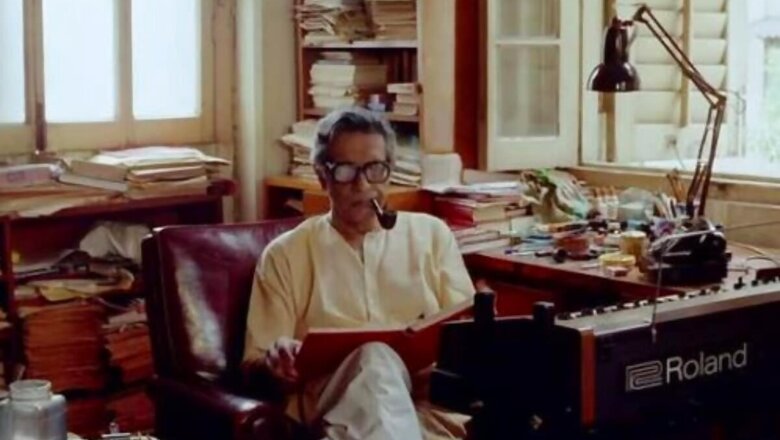

“Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon” – renowned Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa had said this in 1975 about one of the most influential and celebrated filmmakers of all time – Satyajit Ray.

A brilliant illustrator, proficient writer and a master composer, these are some of the terms that we associate with Satyajit Ray, whose centenary we are celebrating today. Even after 29 years of the master auteur’s demise, his films are still studied, analysed and criticised for the amount of detail that they contain. Names of filmmakers across the globe who have been influenced by his cinematic style include Wes Anderson, Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, and Francis Ford Coppola, among others, and rightfully so, because Ray’s mastery over the art of film-making was not only limited to storytelling.

The ambience created by him in his films were mostly accompanied by elements that he used to build from scratch. Elements starting from costume design, the way his characters interacted with each other, where his characters are placed to most importantly, music. Born in a creative Bengali family that boasts of legends like Upendra Kishore Raychowdhuri and Sukumar Ray, Satyajit Ray’s passion for music can be traced back to his childhood which was rich with both Indian and Western music. His passion for music was reflected in almost all of his films and his collaboration with maestro Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan, and his utilisation of classical music in his films is something that has resonated with filmmakers to date.

Ray’s use of certain musical themes was very crucial in building up his characters and depicting what his characters are going through. In Pather Panchali, the serene flute brings out the tranquil village life, whereas, in Jalsaghar, sombre and ominous sitar tones depict the impending doom on the lives of the ‘zamindars’. Or in Teen Kanya, where we see individual themes accompanying individual stories – Ray utilised this component of filmmaking accordingly.

Similarly, in Sonar Kella, the folk song in the local dialect that accompanies the story is successful in bringing out the tradition and culture of Rajasthan. In Joy Baba Felunath, the most poignant moments are accompanied by bhajan, which plays whenever the supposedly antagonist ‘machli baba’ appears on the screen. The soulful bhajan only connects with the idea of the mysticism of Varanasi and someway one can also hear a certain ghazal playing in the background as the movie progresses.

His music was not only limited to instruments as vocals formed a major part of the narrative in films like Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne or Hirak Rajar Deshe. The rhyming lyrics sung by the eponymous characters in the former lend a sense of joy but also conveys the message of the story, whereas, in the latter, songs convey more than words. Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne also has one of the most poignant and unique song sequences in Ray’s filmography, that is, the scene where the Bhooter Raja (King of Ghosts) appears on the screen and chooses eccentric songs as a form of his communication.

In Charulata, his rendition of Rabindra Nath Tagore’s song ‘Ami Chini Go Chini’ achieved the purpose of creating a nuanced relationship in the life of Charu.

A visionary, Ray not only knew the music of his time but also attempted to bridge the gap between Indian and Western styles of music by amalgamating both and creating something with a slightly modern touch but something that also retained its original qualities.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment