views

At first glance, Inside is simply a video game, and for those who still think video games are surficial pixels of entertainment and addiction, often leading to violent outbursts, it could be a path of reconsideration and revelation. This game could change how one looks at video games forever. For the uninitiated, video games have been progressing over the last decade not only as an art form, but as something more, as a tool of political and social change, as a commentary on how we see the world around us, as a mirror, reflecting society and our absurd boundaries back at us.

Inside isn’t as overtly political as, say Papers Please or This War of Mine (rare gems), but it certainly manages to get the job done. The job here would be to make one think, to give one a moment of breathing space, to let one assimilate the visuals and sound into something definite; an idea, a statement. Video games aren’t just about shooting enemies anymore, and Inside doesn’t demand quick reflexes and headshots from the player—just the fact that you play, and absorb what you see. The controls of this game are simple, and it’s a good game to start off with if you’ve ever been curious.

You play as a child, a young boy on a journey. While the exact nature of the journey is not clear, one can attempt to guess, and there are many assumptions you will be called to make. The most beautiful thing about the narrative in Inside is that it is silent, wordless; the visuals you see will leave lasting impressions, the sounds you hear will come back to you at other times, when you least expect it. There is no dialogue, and like any epic, the storytelling itself is so raw and powerful that the absence of spoken words is brandished like a weapon, becoming an advantage to the treatment.

The world is bleak, and colors are dim and muted. Something that comes across is the dark red shirt of the boy you play as, the one tone of resilient hope, fading away but still there, in a largely monochromatic world. You start from the woods, onwards to the farms, and finally make your way to factories, and through them, into secret laboratories. The visuals are both aesthetically astounding and downright chilling; this is a world where things are very, very wrong. Something is indeed brewing, and you catch glimpses of it as you progress, until, in the stunning climax, it rears its ugly, monstrous head.

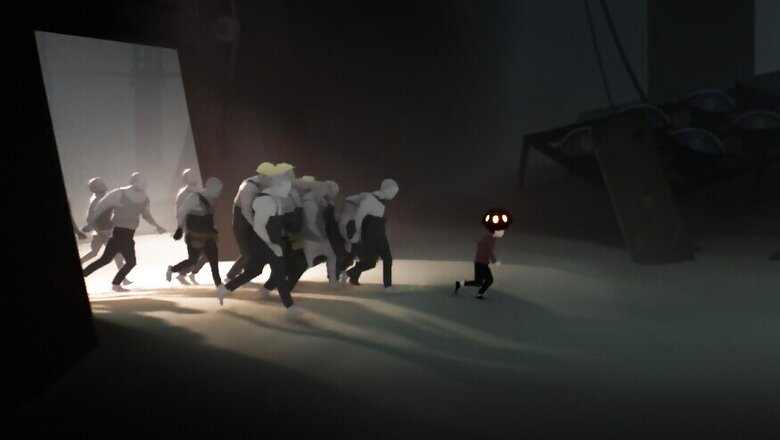

It starts small, with people and guard dogs coming after you, and advances fast to unquestionable metaphors of a surveillance state; beams of searchlight from the sky, stationary robots acting like watchdogs, ready to prevent any so called illegal activity, abandoned genetic experiments, dead things moving in the water. And onward you must push. The child is not equipped to harm anyone. You must, instead, hide, run and use your wits to outsmart those who choose to stop you. If you fail, the result is grisly—the child is drowned, strangled, injected with wires loaded with deadly electricity, ripped apart by dogs, soft splatters of blood spilled time and again.

What is the child heading towards? At first you think it’s a game about escape (and it is, though not in any way you might have imagined)but then you realize the child is heading inwards, towards the heart of this facility of unspeakable experiments and scientists playing God. You notice the workers soon, and something is wrong with them—they’re like zombies, shuffling with their heads downcast, staying in line, moving in perfect accordance to the established order. It is a pure dystopia, and Inside manages to take it a level deeper with elegant touches of science fiction; we’ve all seen mind control before (even Hirok Rajar Deshe, made in our own country by the talented Satyajit Ray comes to mind), but never like this. What Inside does differently, is create a meta-narrative. It takes into account that you, the gamer, are controlling the child through your keyboard or controller, and adds a beautiful and creepy layer to the politics of control, and the ethics of it. There are moments when you slip on a device and control others in the game (adding a layer), and then the person you’re controlling controls another, a layer beneath a layer. It’s a statement to control itself, and the ends of it, and to put it simply, towards the illusion of who’s really in charge, the myth of the puppet master.

I love the game because the interpretations are left to you. I can’t say much without giving away spoilers, unfortunately, but I will say this; my own interpretations have to do with the refugee crisis, history being written by the victors/hosts, and people whose lives have just been torn apart still processing information, blindly obeying orders in a new and unfamiliar land, following orders like sheep, often led to slaughter. The mind control is an allegory to the complete absence of choice, to having one’s hands bound, to falling in line and going where told, shipped off like cattle in train compartments, eerily bringing back the Holocaust in a new time and age, one in which we are supposedly past our barbaric past.

And you see it, you see all of it in the game, through brilliant production and stellar art direction, through the lens of breath taking visualizations and cinematography and life-granting animation. You see things you won’t forget, and it gets you thinking.

Play this game. It speaks on many levels in a time where violence and bloodshed and surveillance are everyday trivialities. It is a beam of light in the darkness, a proud and clear voice in the night and fog.

Comments

0 comment