views

Bahu Begum was always supremely conscious that it was her extraordinary wealth and her exemplary behaviour as an elite Shia noblewoman which granted her a status and reckoning far beyond that of any other single woman in North India. This child of the court of Delhi, raised at the knee of Muhammad Shah Rangeelay himself, had the presence, and the power, that would now bring her into inevitable confrontation with the rising power in India at the time, the East India Company.

In 1780, by the age of around fifty, Bahu Begum was at the centre of a depleted but still impressive court. Decades of patronage had attracted nobility and gentry from Delhi, now older and slightly scuffed, but still a nostalgic symbol of a gilded and endangered way of life. There were people like Nawab Bani Khanam Sahiba, widow of Bahu Begum’s older brother, Najm-ud-Daula, and once a favourite of the Mughal emperor, who was so pious and chaste that she maintained a practically impenetrable purdah. When her own brother came to visit her, she would first bind her hands and feet so that nothing was visible of her save her face.

Rustling with secret decadence was a most precious relic in her trousseau—the coronation robe of Mohammad Shah Rangeelay himself, which he had presented to her husband, a glittering thing of beauty covered with flowers made of rubies, emeralds, and diamonds. She employed her own guards and escort, and maintained many relatives who had all fled to her side to escape the chaos of Delhi. Young women, especially, were sure to be able to count on her generosity when they were in need of help. There were a number of similarly celebrated widows and matrons who also lived with grandeur and elegance in Faizabad. And then there were all the relatives and descendants of Saadat Khan Burhan-ul-Mulk and their entourages, who had also gathered at Faizabad, generating work for all the artisans of the city for their filigree lives of refinement and beauty. Even Bahu Begum’s maidservants lived with the greatest decorum, prohibited from mingling with any male servants.

Lending a further layer of enamelled sheen to Faizabad were the great khwajasaras of Nawab Begum and Bahu Begum, who by now were well established men with grand retinues of their own, sometimes comprising thousands of soldiers and innumerable servants and hangers-on. When Jawahar Ali Khan rode out of the city for hunts, for example, he was accompanied by a glittering and colourful procession of soldiers—there was a Bundela unit in red turbans and belts, a ‘Sabit Khan’ unit in mango-green livery, irregulars in black livery, regulars in red, Mewatis in white—this procession preceded by heralds on horses loudly shouting out the Khan’s glory.

The severity of the purdah Bahu Begum observed brings us to the piquant question of her appearance. There are, of course, no known portraits or likenesses among the thousands of works commissioned, indeed no contemporary chronicler had the temerity or indecency to mention anything about her appearance at all. ‘The adab or etiquette of society’ wrote a historian, ‘demanded that they remain confined’. The closest likeness we might observe are the portraits of her brother, Salar Jang, to whom she was particularly close. In Zoffany’s famous portrait he is a golden-complexioned, elegant, and well-proportioned man, with an expressive and sensitive face. Interestingly, we know more about that most intimate of a purdah-bound woman’s feature—her voice.

For a veiled woman, not only was a glimpse of her features absolutely forbidden, but the very timbre of her voice was also never to be heard by any male outside the zenana. When communication was necessary, the begum would be seated behind a heavy curtain which would muffle all sound, and she would interact with the outsider via a khwajasara, or a woman attendant. The message spoken by the man sitting in front of the curtain, though perfectly audible to all, would be relayed to the waiting begum by her intermediary, and she would then whisper her response back to the woman servant or khwajasara.

But, when overcome by emotion, usually fierce anger, Bahu Begum sometimes dispensed with these niceties, and so we know she had a strong, loud voice which carried like that of a general’s in a war room. During the protracted imprisonment of her khwajasaras in 1782, she once sent for her brother Salar Jang to present himself to the door of her zenana for an explanation. Salar Jang was described by an Englishman as ‘not brilliant but experienced…mild and just in (his) administration and beloved by all’.

Entirely unequal to the task, therefore, and aware of the power of his sister’s fury, Salar Jang reluctantly presented himself and Bahu Begum ‘spoke to him with so loud a voice that everyone anywhere near the door could hear her.’ Salar Jang was so shaken that he was unable to utter a response, and ‘left in a few minutes trembling and alarmed, while the Bahu Begum shouted to his retreating back: “You may go; all that I looked for from you, I hope my God will do for me.”’

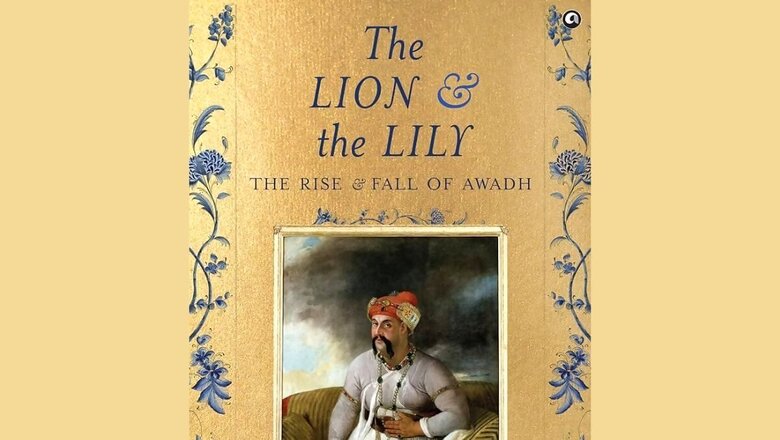

A Portrait of a Nawab

Scholars are uncertain when it comes to evaluating the legacy of Shuja as a patron of art. Unlike earlier emperors and patrons, there is a scarcity of clearly signed and attributable albums, and an identifiable stylistic imprint for Awadh in the second half of the eighteenth century. What is clear, however, is that the eighteenth century in northern Hindustan was often a very violent, chaotic, and turbulent time and this affected not only the artists and the art, but also the historiography of art. For in the eighteenth century, there are very few of the expansive and erudite treatises on art which flourished in the seventeenth century, or the steady production of exquisite muraqqas in impeccable taste and style that the earlier Mughal emperors had most felicitously ensured. Instead, in the eighteenth century and then in 1857, the great centres of Mughal art would be raided and destroyed time after time, with a violence that was visceral and all-consuming and the cities of Delhi, Faizabad, Lucknow, Murshidabad would be torn apart, brick by brick, and set ablaze, folio by folio.

Art was first ‘gifted’, then destroyed, looted, and hidden away, and even today, individual folios of beautiful late Mughal art appear on the market, their provenance unknown. Entire collections were seized from their patrons, taken to the West, and then confusingly rebaptised with the name of the British legator, such as the so-called Clive albums and the Douce albums so that the origins of these works remain shrouded in mystery and etymology. Even within the country, museums in India remain opaque in their dealings, and many priceless collections and paintings are hopelessly and pointlessly beyond the reach of any but the most intrepid scholars.

It is, therefore, not surprising that it is difficult to attribute entire muraqqas to individual patrons, or to trace the trajectory of individual artists with certainty. In contrast to this there are the impeccably catalogued, sealed and signed collections of Polier and Gentil, deposited in the safety of European museums, their enchanting images and personalized notes an irresistible counterpoint to the nawab’s apparent absence.

What is indisputable is that art flourished in Awadh in the second half of the eighteenth century like it had never done before. Artists experimented with great freedom with themes of naturalism, and detailed backgrounds were now carefully painted in. Calligraphers arrived in Awadh too, including the Persian-born Hafiz, who became a sarkari calligrapher as well a teacher of calligraphy.

Apart from being patrons themselves, the nawabs could also buy muraqqas and folios as soon as they appeared on the market, these gorgeous items of prestige sometimes coming straight from the ateliers of the emperors, as Delhi was despoiled time and again. And though no written records remain of the migration of these Mughal artists, scholars have studied the styles of paintings, to painstakingly piece together the history of some of the artistic legacy of Awadh.

Awadhi artists in the second half of the eighteenth century became deeply interested in light and shadow, and the creation of volume and space. Some of these ideas, naturally, were occasioned by exposure to European art. After all, in the sixteenth century under Akbar and then Jahangir, Mughal artists had studied European art extensively, absorbing ideas about space and depth and naturalism with great subtlety and craft. The presumption was that after this cataclysmic clash of Persianate and European art, Mughal artists would inevitably follow the path of greater realism in their paintings. This, however, was not the case, and the grumbling criticisms of scholars who found this baffling grew loud.

But as art historian Kavita Singh has so peerlessly shown, there was no smooth transition to European style realism because the Mughal artists chose not to do so and allowed themselves the liberty of using the Persian style, or the European one, or indeed a hybrid of both at once if the painting required it. Some scholars now see the style of artists as visual language, to be ‘read’ only by the discerning, using a subtle Morse code of signals.

Indeed, to be able to correctly understand or ‘read’ such a painting, explains Kavita Singh, the paintings needed to be understood alongside ‘poetry, rhetoric, philosophy and theology—and also astronomy, astrology, music, medicine, physiognomy and mathematics’ in addition to the dynastic history and political ideologies of the time. And as it was with the Mughal artists of the sixteenth century, so it was with Awadhi artists in the eighteenth century too.

The above article is an extract from the book, ‘The Lion and the Lily’, by Ira Mukhoty, published by the Aleph publication. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment