views

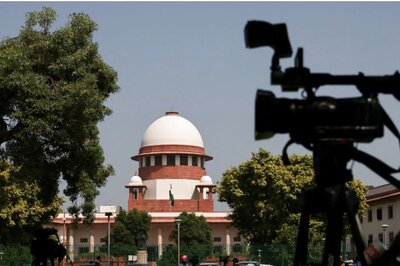

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) is a legislative enactment passed by the Parliament of India on 11 December 2019 to amend the Citizenship Act of 1955. This amendment allows Indian citizenship to be granted to religious minorities, including Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians, who fled from the neighbouring Muslim-majority countries of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan due to religious persecution, or fear thereof, before December 2014.

Under the CAA 2019 amendment, migrants who entered India by 31 December 2014 are eligible for fast-track Indian citizenship. The amendment reduced the residence requirement for naturalisation from eleven years to five. Its aim is to provide a dignified life to persecuted religious minorities who are unable to freely practise their faith in their home countries.

Under the Citizenship Act of 1955, illegal migrants were ineligible for Indian citizenship. They could apply for citizenship under Section 5 of the Citizenship Act, but if unable to provide evidence of Indian origin, they were required to pursue citizenship through naturalisation under Section 6. This often resulted in the deprivation of numerous opportunities and benefits.

The exclusion of Muslims from the amendment has been criticised by India’s Opposition parties, legal scholars, sections of civil society, leftist student groups, and others for being unconstitutional in light of India’s secularism, the right to equality, and democracy. In this article, I will assess whether the CAA violates international law, particularly concerning the right to a nationality and the principle of non-discrimination.

An analysis of India’s international obligations is relevant to the current litigation because Article 51(c) of the Constitution of India requires the State to ‘foster respect for international law and treaty obligations in the dealings of organised peoples with one another’.

The right to a nationality is enshrined in Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that “everyone has the right to a nationality” and that “no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality or denied the right to change his nationality.” International law stipulates that it is for each State to determine, through domestic law, who its citizens are. This determination must be consistent with general principles of international law, particularly those relating to the acquisition, loss, or denial of citizenship. The right to nationality qualifies as a civil and political right.

As is clear from Article 15 of the UDHR, the right to nationality, in a general sense, relates to the acquisition, change, and loss of nationality. The acquisition covers the automatic conferment of nationality at birth by descent (jus sanguinis) or based on the place of birth (jus soli), as well as the subsequent acquisition of nationality ex lege, for example, through marriage, after a certain period of residence, by declaration, registration, or upon application through naturalisation, or by option. The change of nationality relates to the possibility of dual or multiple nationality or the right to renounce one’s nationality. Loss of nationality, finally, includes all forms of forfeiture of nationality, whether through renunciation, withdrawal, lapse, or nullification. The rights and obligations protected by the right to nationality apply to individuals in all procedures relating to the acquisition, change, and loss of citizenship.

The international legal framework does not currently provide for a general right to the nationality of a specific state. In other words, the right to nationality in international law does not grant a right to be naturalised in a particular state. Given the principle that states are largely free to determine the criteria for the acquisition of nationality, there are few rules obliging states to grant their nationality to an individual.

The prohibition of discrimination forbids unjustified unequal treatment in the application of nationality laws. States may not discriminate on the basis of race, colour, gender, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, economic situation, birth, age, disability, or other status. In other words, states must observe the principle of non-discrimination in the application of laws relating to the acquisition, enjoyment, change, and loss of nationality. Differential treatment based on a protected characteristic must be grounded in an objective and reasonable justification.

The question is whether the CAA constitutes discrimination. There is an objective and reasonable ground that justifies the different treatment under the CAA. This rationale is rooted in the Partition, during which Pakistan (and later Bangladesh) was formed based on religion. Additionally, during Partition, Hindus and Sikhs also migrated from Pakistan to Afghanistan.

The Nehru-Liaquat Pact, signed in April 1950, committed the Indian and Pakistani governments to protect the interests of minorities in their respective countries. In the years immediately following Partition, the migration of refugees posed a serious threat to the security and stability of newly independent India and Pakistan.

Figures from both Pakistan and Bangladesh show a significant decline in minority populations, with a large-scale exodus of minorities from these Muslim-majority neighbouring countries. The number of Hindus and Sikhs in Afghanistan has also dramatically decreased since the fall of the Communists in 1992. After various rulings under the Mujahideen and Taliban periods, the Hindu and Sikh communities now consist of only a few hundred individuals. This stands in stark contrast to the increase in Muslim minorities in India.

The CAA bill grants Indian citizenship, which was necessary to protect the human rights of persecuted minorities (who have been living as illegal migrants for decades) from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. These countries have been incapable of protecting the rights of their minorities. Therefore, India has made this amendment, considering it its duty to protect its citizens of undivided India on humanitarian grounds.

The CAA does not confer citizenship indiscriminately; only individuals who entered India by the cutoff date of December 31, 2014, are eligible to apply for Indian citizenship through the Central government. Notably, this amendment does not affect the citizenship of existing Indian nationals of Muslim faith. The CAA prioritises six minority communities displaced due to extreme religious persecution in these three countries, provided they meet the prescribed criteria.

In conclusion, under international law, India has the sovereignty to determine who can apply for Indian nationality and under what conditions. Therefore, the CAA is valid in the context of international nationality law. Regarding the alleged discrimination against Muslims from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, there is a reasonable and justified basis for the CAA, which is directly related to Partition and the need to protect religious minorities in these three countries, who have faced a significant decline due to religious persecution and other fears.

The author is an expert in International migration law. He works as a senior lawyer at the Ministry of Social Affairs – Netherlands and is a deputy judge at the district courts in Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment