views

Doha: The agreement just signed by American and Taliban negotiators opens the way for direct negotiations between the insurgents and other Afghans, including the country’s government, on a political future after the United States ends its military presence. The negotiations could also result in a cease-fire.

Here are the main points in the agreement, and a look at how events could unfold.

A Gradual US Troop Withdrawal Will Begin

The United States has agreed to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan in exchange for assurances by the Taliban that it will deny sanctuary to terrorist groups like al-Qaida. Right now, the United States has about 12,000 troops in the country, down from about 100,000 at the peak of the war nearly a decade ago. They are supported by several thousand others from NATO allies.

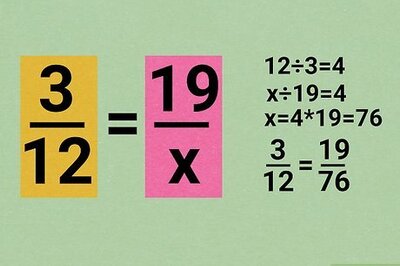

The two sides have agreed to a gradual, conditions-based withdrawal over 14 months. In the first phase, about 5,000 troops are to leave within 135 days. During the gradual withdrawal, the Taliban and the Afghan government would have to work out a more concrete power-sharing settlement. That time frame would give the government the cover of US military protection while negotiating.

The Taliban Pledged to Block Terrorist Groups

The United States invaded Afghanistan because the Taliban government had given safe haven to al-Qaida, which conducted the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Over the years, even as al-Qaida has been decimated by years of US military operations, the Taliban refused to publicly disavow the group, which still pledges allegiance to the Taliban’s supreme leader. As part of the deal, the Taliban commit to keeping al-Qaida and other terrorist groups from using Afghan territory to stage attacks against the United States and its allies.

One fact that the agreement sidesteps: A dominant faction within the Taliban, the Haqqani Network, is still classified as a terrorist group by the United States, having carried out dozens of deadly suicide bombings. The leader of the network, Sirajuddin Haqqani, is the Taliban’s deputy leader and operational commander. The United States and the Taliban are to establish a joint monitoring body in Qatar, where their negotiations have been held, to assess progress on the commitments.

The United States also committed to working to release 5,000 Taliban prisoners, held by the Afghan government, and 1,000 members of the Afghan security forces held by the Taliban side by March 10, before both sides are expected to sit down for direct negotiations. The United States will also review sanctions it has on Taliban members and start diplomatic efforts with the United Nations to remove the penalties.

Complicated Talks Between Afghans Come Next

The agreement between the United States and the Taliban unlocks a difficult but crucial next step: negotiations between the Taliban and other Afghans, including the government, over future power-sharing. Those talks are expected to start soon, within 10 days or so. But the Taliban, who led most of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 before they were toppled by the US military invasion, refuse to recognize Afghanistan’s democratic government. The goal of their insurgency has been returning to power and establishing rule based on their view of Islam.

Other major issues, including women’s rights and civil liberties, are also at stake. Many Afghan women have expressed concern that they have been sidelined from the process, and they fear that protections created for them over the past 18 years could be bargained away to the ultraconservative Taliban movement.

Divisions inside Afghanistan will complicate the negotiations. The democratic side has been bitterly divided by a disputed election, with the main challenger declaring he would form his own government after President Ashraf Ghani won a second term in office.

The Deal is Tied to Reducing Bloodshed Immediately

For much of the negotiating process, the American side demanded a cease-fire that could pause the bloodshed, in which dozens are killed daily, and create space for talks over the future of the country. With violence as their main leverage, the Taliban refused that demand in the early stages of the talks, saying they were willing to discuss it only in negotiations with other Afghans once the United States promised to withdraw its troops.

Eventually, the two sides found a compromise: a significant “reduction in violence” that would not be called a cease-fire. The signing of the deal was conditioned on a seven-day test of that violence reduction, which officials said largely worked. Attacks across Afghanistan, which normally would number as many as 50 to 80 on any given day, dropped to below a dozen.

The reduction in violence is expected to continue into the next phase of the process, until the two Afghan sides can agree to a more comprehensive cease-fire.

Mujib Mashal and Russell Goldman c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment